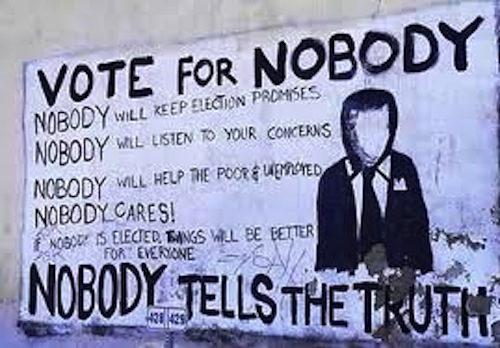

We live in a time of immense challenges, amid international upheaval, ecological imbalance, and economic uncertainty. Humanity’s capacity to improve lives may never have been greater, yet it is matched by new powers to destroy and divide. Unfortunately, our government has failed to meet these challenges. Despite obvious hunger for political change, too many Americans are stuck with a “lesser of two evils” choice without a viable candidate to speak for them. Decisions to vote are motivated far more by fear than by hope.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that many of our nation’s most fervent and astute believers in change abandon representative democracy and any hope to win seats and transform government power and policy. Instead they focus on non-electoral organizing, from high-profile movements like Occupy Wall Street to the less noticed, yet indispensable work of protecting and securing local progress.

Their efforts are worthy, of course, but the experience suggests that such efforts’ effectiveness is greatest when combined with electoral politics. Engaging with the people of a community, state, or nation in the enterprise of seeking votes and winning representation provides a means to build public support and, ultimately, make a government an ally in seeking change. In clashes between corporate power and people, it’s better to have government on your side as an instrument of the public good.

___________________________________________

Many of our nation’s most fervent and astute believers in change abandon representative democracy and any hope to win seats and transform government power and policy.

Instead they focus on non-electoral organizing.

___________________________________________

The glaring disconnect between the urgent demands of the times and the passion and talent of American activists on the one hand, and our narrow, depressingly static electoral politics on the other is rooted in outdated voting and governing laws that discourage creativity, depress competition, diminish debate, and destroy accountability.

It’s time for electoral reforms designed to embrace the beauty and power of people coming together for the common good. Activists from the Tea Party, No Labels, Occupy, and less publicized movements may often disagree on policy, but we all ultimately benefit from translating their energy into a voice in government. Doing so demands electoral reforms designed to uphold core principles: Fair elections demand real choices no matter where you live. Real representation means being able to join with like-minded people to elect candidates in proportion to your voting strength. Private money must not exaggerate the power of the few. Democracy rests on our ongoing participation.

Certainly other nations have long ago stopped imitating the American model. Nearly all democracies hold at least one of their national legislative elections with proportional representation rather than winner-take-all rules that exclude so many people from sharing power. No well-established nation (with a presidential office that wields real power) has an Electoral College, and few have plurality voting. Instead they have a national popular vote with a majority requirement, thereby making every vote equal and accommodating voter choice and avoiding “spoiler” effects. They typically have automatic voter registration and establish an affirmative right to vote in their constitution, removing access to suffrage from crass partisan calculations. They often provide free access to public airwaves and other means to provide equity in spending, which do much to check the influence of big money when combined with proportional representation systems that weaken the stronghold of swing voters who are most prone to be affected by campaign ads.

In short, these nations do far better at living up to the motto of my organization FairVote: respect for every vote and every voice. Talking with young people from emerging democracies with such rules provides a marked contrast with talking with young Americans about elections. Their national governments and level of democracy may be far from perfect, but they have hope about the future and passion for understanding the impact of different rules. They believe that elections and politics matter. It’s a far cry from the virtual eye-rolling of so many American students who can’t even believe you’re serious when talking about elections as a meaningful route to change.

The Core Reform: Proportional Representation

The foundation for a more vital electoral democracy is replacing winner-take-all elections with forms of proportional representation (PR) that are constitutional in the United States and already used in some local elections. Even our own political forerunner, the United Kingdom, has adopted PR for electing representatives to the European Parliament, the Scottish and Wales regional assemblies, the London City Council and Scottish local councils. As the Arab Spring movement takes root, its most democratized countries are adopting forms of proportional representation, just as was true of Eastern Europe nations after the fall of the Communist bloc. Indeed, the degree of proportionality in an emerging democracy is usually the best thermometer of how democratic that nation truly has become.

PR takes many forms and cannot be understood by any one example of its practice, but the common thread is that more voters elect preferred candidates from a broader spectrum of choices, and like-minded voters (be it a party or some other measure of common views) win representation in close relation to their share of the vote. Winning a majority of more than fifty percent of the vote should result in winning a majority of seats, but not all seats. Ten percent of the vote means one out of ten seats and twenty-five percent of the vote means one out of four.

___________________________________________

Nearly all democracies across the world hold at least one of their national legislative elections with proportional representation rather than winner-take-all rules that exclude so many people from sharing power.

___________________________________________

American forms of PR typically involve voting for candidates in multi-seat districts. In Cambridge, MA, they have a ranked choice voting system where earning the strong support of just over 10% of the vote earns a seat on the nine-member city council. In 2009, a young Asian American grad student ran a strong campaign using new forms of social networking, and surprised the old guard by earning a seat. In 2011, he ended up earning the most first choices and won easily. Indeed, the Cambridge city council has had a person of color on its council for more than a half-century, and always represents people with a mix of opinions and from a mix of neighborhoods. Similar systems include cumulative voting, now used in Peoria, IL, and Amarillo, TX, after being adopted to settle voting rights cases and used for more than a century (from 1870 to 1980) to elect the Illinois House of Representatives, during which time nearly every corner of the state always had representatives of both major parties.

Congress could impose proportional voting for U.S. House elections with a simple change in federal law. That’s not likely soon, but it at least could repeal the 1967 law mandating single-member districts, restoring states with the power to try different systems, as they regularly did before 1967. FairVote’s new Fair Voting Solution report showcases just how powerful it would be to adopt American forms of proportional representation. Our interactive map allows an easy comparison between congressional elections as they are and congressional elections as they could be. At least one Democrat and one Republican would likely win in every multi-seat district, and the number of voters with at least one woman representative would likely triple from 17% to more than half of the electorate.

We also need to be more ambitious in seeking PR in cities. Racial minorities in cities can seek PR systems in lawsuits brought under the Voting Rights Act to change exclusionary, winner-take-all voting systems. Women can be reform allies, as PR consistently results in more women running and winning. We’re looking at states with initiative rights—like Maine or Montana—for a sustained effort to build a movement ready to go for a statewide ballot measure to replace winner-take-all elections with proportional voting.

Reforms that Enhance Proportional Voting and a Roadmap for Change

We can do much to begin the transition from our two-party duopoly to a system where voters have real choice among more parties and independents. Reformers have made great headway in winning the instant runoff voting form of ranked choice voting (IRV). Designed for one-winner elections, IRV allows longshot candidates to run without being attacked as “spoilers” by upholding the principle of majority rule. Voters can rank candidates in order of choice (a first, second, and third) and election officials use those rankings to simulate traditional runoff elections. In 2000, for example, a Florida voter backing Ralph Nader might have indicated Al Gore as a compromise second choice. Once it was clear that no candidate has a majority, Nader would have been eliminated—and ballots cast for him moved to their second choice.

___________________________________________

Young people from emerging democracies with proportional representation tend to believe that elections and politics matter. It’s a far cry from the virtual eye-rolling of so many American

students who can’t even believe you’re serious when talking about elections as a meaningful route to change.

___________________________________________

IRV has been won recently in more than a dozen cities, including San Francisco, Oakland, Minneapolis, and Portland, ME. While a winner-take-all system, it liberates voters to indicate their true preferences and boosts candidates who work hard at grassroots, neighborhood-based politics. It has weakened the influence of big money because it turns out that the best way to secure voter support when they can ran candidates is through direct interaction. Knocking on doors and attending local events can show people that you will listen, even if they disagree with you. Meanwhile, the traditional big money tactics of highly negative attacks on opponents are less effective when you have more than one opponent—you may knock down support for one candidate, but that doesn’t necessarily help you win.

IRV has had significant success on the ballot, but is at a key point in its reform trajectory. Advocates are under-funded, and local partisans measure every use of IRV with a simple yardstick: did their side win? If not, they can finger the “exotic” new system and attack it before it becomes firmly settled as part of a city’s politics. That alone wouldn’t necessarily be a problem, but we also must work hard simply to implement IRV: fighting with voting equipment vendors refusing to implement it and with overburdened election officials not wanting to take on new tasks. If we can sustain and steadily expand IRV’s use, those administrative hurdles will soon disappear. With a straight choice between the status quo and IRV that doesn’t include new costs, we will win.

Indeed, I believe we can win major electoral reforms far sooner than most people believe. Change breeds change, and our politics has reached a breaking point: current rules just don’t work when the major parties are so polarized and when new voices are shut out. In the midst of all our non-electoral priorities and efforts to make progress within the current rules, we must keep our eye on the electoral reform ball: with smarts, good timing, and resources, we can make the United States the truly representative democracy so urgently needed as we move forward into a perilous, but promising future.

Check out the The Fair Voting Solution for U.S. House Elections, featuring an interactive map

Read about other threats to democracy in the complete series, “Seven Sins Against Democracy”

Rob Richie has served as the Executive Director of FairVote since 1992. His writings have appeared in the nation’s leading newspapers and in nine books, including as co-author of Every Vote Equal about establishing a national popular vote for president and of Whose Votes Count about the case for proportional voting and ranked choice voting. He has been a guest on NPR’s All Things Considered and Talk of the Nation, C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, NBC News, CNN, FOX, Bloomberg News, Democracy Now and MSNBC and addressed conventions of the American Political Science Association, National Association of Counties, National Association of Secretaries of State, Free Press, National Latino Congreso and National Conference of State Legislatures. He serves on the Haverford College Corporation. He and his wife Cynthia Terrell have three children.

Rob Richie has served as the Executive Director of FairVote since 1992. His writings have appeared in the nation’s leading newspapers and in nine books, including as co-author of Every Vote Equal about establishing a national popular vote for president and of Whose Votes Count about the case for proportional voting and ranked choice voting. He has been a guest on NPR’s All Things Considered and Talk of the Nation, C-SPAN’s Washington Journal, NBC News, CNN, FOX, Bloomberg News, Democracy Now and MSNBC and addressed conventions of the American Political Science Association, National Association of Counties, National Association of Secretaries of State, Free Press, National Latino Congreso and National Conference of State Legislatures. He serves on the Haverford College Corporation. He and his wife Cynthia Terrell have three children.

Unbound Social