“I’m sorry to have to tell you that you have cancer of the rectum.”

I firmly believe now that such news should be delayed at least until a patient is a little less foggy from anesthesia.

It was a good thing my wife was with me on that Friday, August 24, 2012; I didn’t hear another word the gastroenterologist said. My mind was too busy with a confused and panicky welter of jumbled thoughts. Cancer?? How did that happen? Cancer of the WHAT?? Is this going to kill me? I’m going to have to drop out of school, aren’t I? Really, cancer of the WHAT?? At least I have health insurance.

For now.

Indeed, I was covered by a basic student plan offered by Union Presbyterian Seminary, where I had just finished my second summer of language school two days before. I dare say that if I had not that coverage, I would not have made the visit to the doctor that resulted in the consultation with the gastroenterologist that resulted in the colonoscopy that revealed the cancer. So already, my access to health care – actually, my access to health insurance – was the very reason my cancer was discovered early enough to be treatable.

___________________________________________

According to pre-ACA law, it would be entirely possible that I could be denied access to health insurance, charged such a fee that I’d be unable to afford it, or offered only insurance that would not cover any cancer treatment at all.

___________________________________________

To this point, I had stayed somewhat quiet concerning the Affordable Care Act. I thought the general idea was good, but I didn’t know enough to be sure if it was too much or not enough. Suffice it to say I started paying much more attention after my diagnosis. Which, in August 2012, was just in time for my access to care to become a political football.

After all, student health insurance isn’t permanent; I wouldn’t be eligible for it any more after I graduated. So, if the ACA were to be thrown out by the courts or repealed by a new president and Congress (both prospects that seemed very real in August 2012), I would be going into my graduation with a great big scarlet “C” on my health record – just when I’d need to be looking for insurance (I believe I’ll be a well-qualified pastor, but I’m not so naïve to think I’ll walk right off the graduation stage this May into a pulpit, so there’s going to be some lag time in which I’ll need health insurance). According to pre-ACA law, it would be entirely possible that I could be denied access to health insurance, or charged such a fee that I’d be unable to afford it (particularly as a newly-graduated seminarian with the mound of healthcare debt I’d accrued even with my insurance coverage), or offered only insurance that would not cover any cancer treatment at all. All of a sudden, I had a great deal riding on the future of the ACA and its successful implementation.

After all, student health insurance isn’t permanent; I wouldn’t be eligible for it any more after I graduated. So, if the ACA were to be thrown out by the courts or repealed by a new president and Congress (both prospects that seemed very real in August 2012), I would be going into my graduation with a great big scarlet “C” on my health record – just when I’d need to be looking for insurance (I believe I’ll be a well-qualified pastor, but I’m not so naïve to think I’ll walk right off the graduation stage this May into a pulpit, so there’s going to be some lag time in which I’ll need health insurance). According to pre-ACA law, it would be entirely possible that I could be denied access to health insurance, or charged such a fee that I’d be unable to afford it (particularly as a newly-graduated seminarian with the mound of healthcare debt I’d accrued even with my insurance coverage), or offered only insurance that would not cover any cancer treatment at all. All of a sudden, I had a great deal riding on the future of the ACA and its successful implementation.

___________________________________________

The number of pre-existing conditions for which coverage could be denied under previous law is varied and extensive, from acne to diabetes to obesity to cancer. Perhaps the most horrifying example is that, prior to ACA enactment, seven states allowed insurers to define a survivor of domestic abuse to be defined as having a “pre-existing condition” and to deny health insurance access to that survivor.

___________________________________________

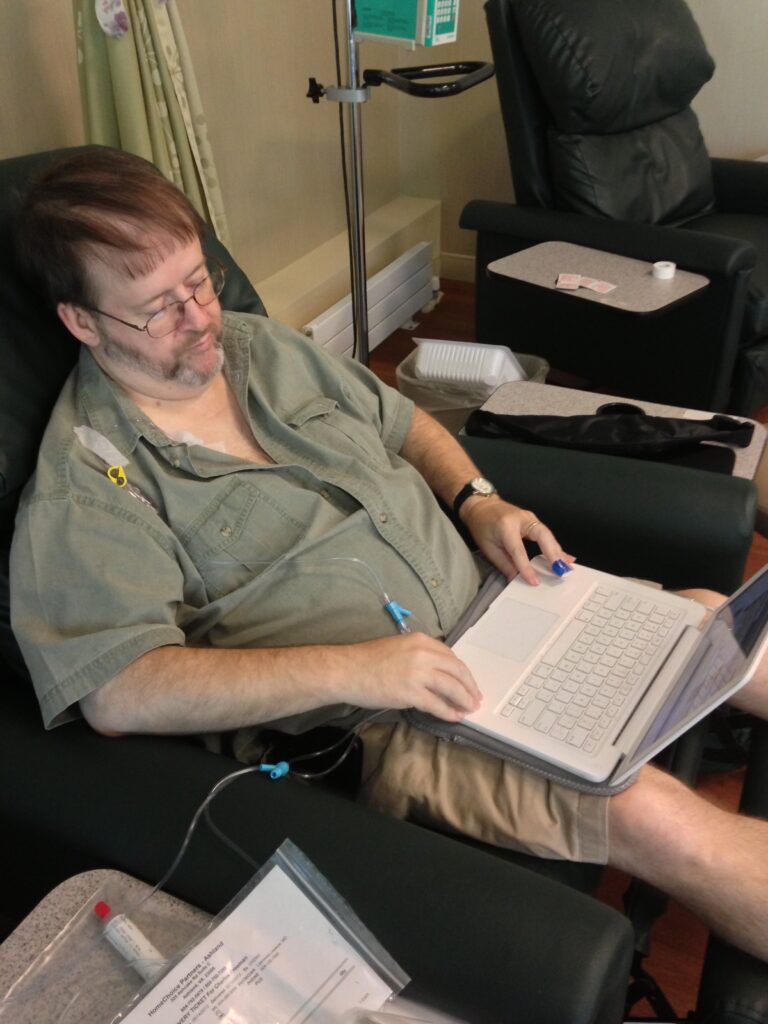

Meanwhile, with the gracious and generous help of many classmates and professors and the unbelievable support of my wife Julia, I made it through my middle year at Union while undergoing radiation treatment in the fall, surgery in December 2012, and chemotherapy from March to June of 2013. (Of course, I’m not at all “in the clear” with regard to cancer; I visit the oncologist again next week.) The Supreme Court did not overturn the ACA, and a new president was not elected, so at least for now I’m covered and can continue to be covered once I graduate. I considered myself very fortunate.

Little did I know how fortunate I was.

In September 2013, I started an internship with the Virginia Interfaith Center For Public Policy, which teaches and engages in advocacy and education with persons of many Christian denominations – as well as other faiths – in the state of Virginia. On the state level, ACA implementation hinges mostly on two issues: the expansion of Medicaid to cover the “Medicaid gap” between those who can afford insurance on the health exchange with subsidies and those eligible for Medicaid already (and Virginia’s eligibility requirements for Medicaid are some of the stingiest in the country [i]), and the decision whether a state will implement its own health exchange or not. Virginia has done neither, though Medicaid expansion is still alive in the Virginia legislature (as of 3/3/14). As a result, thousands of Virginians have been unable to improve their access to health care by gaining access to health insurance.

At least for now, though, the ACA provision concerning coverage for preexisting conditions remains in place, and this has made a difference for thousands already in Virginia and across the country. “Preexisting conditions” is a rather broad term, albeit fairly sufficiently descriptive. A child born with a congenital defect or genetic condition of any sort; a man or woman with a degenerative disease like ALS; or a lucky guy like me who has known the life-changing experience of cancer: all could have been denied coverage in the past or offered only a very limited and extremely expensive plan. The number of pre-existing conditions for which coverage could be denied under previous law is varied and extensive, from acne to diabetes to obesity to cancer. Perhaps the most horrifying example is that, prior to ACA enactment, seven states allowed insurers to define a survivor of domestic abuse to be defined as having a “pre-existing condition” and to deny health insurance access to that survivor.

The Presbyterian Church (USA) has been no stranger to the national debate on access to health care. One statement from the General Assembly makes clear the denomination’s interest in and concern for universal access to health care:

The Christian should manifest active concern in the failure of society to marshal its full resources for health for all people. In countless cases, health is denied because of the lack of funds by the individual in need of medical services and the lack of medical resources. In the name of the Great Physician, we favor federal legislation that will join appropriate civic, professional, and other bodies, in co-operation with government, in providing the means for adequate medical care wherever needed.

That statement, by the way, came from the 158th General Assembly, in 1946. Presbyterians have continued to speak through General Assemblies in intervening years, as several articles in the last two weeks have outlined. The 203rd GA, in 1991, issued a comprehensive statement on Christian responsibility and health care access that leaves no room for doubt:

When persons are excluded from health care, they are in effect being told that their uniqueness is not valued and their contributions to the well-being of the larger community are less important. For all these reasons, we reject any attempt to exclude people from health care or to limit their access on the basis of race, sex, income, age, social or ethnic group, demography, disability, existing condition, and so forth.[ii]

Indeed, Presbyterians have at times been among the boldest voices of faith in calling for just and equitable access to health care for Americans, and that witness has not lessened with time. It makes me glad to be a Presbyterian.

All of this was far in my future that Friday in August 2012. For now, I’m focusing mostly on graduating in May, getting certified as ready to receive a call by the Presbytery of Northern Kansas this spring, and setting about the serious business of seeking a call. In the meantime, my wife has plunged into the ACA-based health insurance exchange and found a plan that works for us upon my graduation; it looks like it will cost slightly less than our current seminary-based plan, and offer much stronger benefits.

All of this was far in my future that Friday in August 2012. For now, I’m focusing mostly on graduating in May, getting certified as ready to receive a call by the Presbytery of Northern Kansas this spring, and setting about the serious business of seeking a call. In the meantime, my wife has plunged into the ACA-based health insurance exchange and found a plan that works for us upon my graduation; it looks like it will cost slightly less than our current seminary-based plan, and offer much stronger benefits.

And we’ll be able to sign up for it – even though I’m a cancer patient.

[i] For example, a family of four earning between $7,000 and $23,000 a year falls into the “Medicaid gap,” not eligible for Medicaid or for subsidies for marketplace coverage. Source: vaconsumervoices.org/medicaid-expansion/

[ii] 203rd General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA), Resolution on Christian Responsibility and a National Health Plan, 17. Can be downloaded here. The report also summarizes and highlights previous GA actions on health care, including the 1946 report noted above.

AUTHOR BIO: Charles Freeman is a final-level student at Union Presbyterian Seminary and a choral section leader at Ginter Park Presbyterian Church in Richmond,Virginia. Before pursuing theological study, he was an academic musicologist, receiving his Ph.D in historical musicology from Florida State University and teaching at several institutions, most recently the University of Kansas.

Click here for the rest of this week’s articles.

Read more articles in this series.

Unbound Social