Appreciating Hip-Hop’s Justice Roots

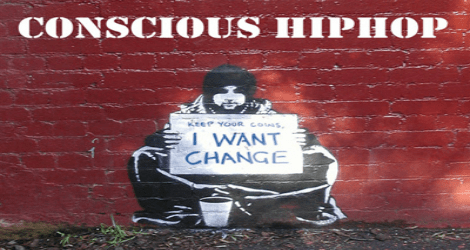

By Edward Vogel, co-creator of “Rhymes and Reasons” Hip-hop has become one of the biggest cultural phenomena of the last thirty years but it is often misunderstood, especially by people committed to social justice. How can an artform that is often misogynistic, homophobic, and materialistic speak to the same issues that define the radical love of the Gospels? How does hip-hop align with the Catholic Worker Movement? Answer: Hip-hop is an attempt to document a history that our society is structured to ignore. It is the story of the poor, the imprisoned, the beaten down, as well as a story of the Beatitudes and the Works of Mercy. Taking the time to appreciate hip-hop will help you cross the border into a deeper understanding of another group of people and will offer a better understanding of what social justice truly is. Read and Print as PDF

Read and Print as PDF

I was born into a privileged, middle class, white family in Lansing, Michigan with two parents and a firm grip on upward mobility. I was born into a Catholic family residing in a strong Catholic community where I would be supported and nurtured in my faith tradition from a young age. I attended the local Catholic school where I enjoyed a great education and was introduced to the idea of social justice.

But I had another privilege unconsidered by most: I was born in one of the first generations where hip-hop music and culture preceded me. When I was a kid, hip-hop culture, style, and rap music were everywhere. One of my brothers blasted his rap CDs on his stereo before my father decided that “vulgar” music was not welcome in his home. After that, I didn’t listen to much hip-hop, only the songs that crossed over into the pop mainstream from artists like Puff Daddy, Notorious B.I.G., the Beastie Boys, Outkast, and Will Smith.

In high school, that all changed.

I had started listening to Rage Against the Machine when I was only a boy. I loved Rage; they were raw, they were powerful, and they spoke to the same social concerns that my parents and school emphasized only in a different type of language and perspective. They released their last studio album, Renegades, which was also a cover album, during my freshman year of high school. My favorite song on the album was “Microphone Fiend”, and after reviewing the liner notes, I discovered that a DJ and rapper duo named Eric B. & Rakim had originally recorded the song. I got my hands on the original version and it blew my mind. Eric B & Rakim became a gateway for me into rap music. I couldn’t stop listening. I started to search for more. I listened to Public Enemy, De La Soul, and A Tribe Called Quest. All of these artists spoke to me because they discussed social concerns.

___________________________________________

Being born out of resistance, hip-hop is in many ways an act of solidarity in and of itself—the music, an oral history detailing why and how people struggle to survive

in a society that marginalizes them.

___________________________________________

My interest in hip-hop, however, largely stopped at anything released after 1994.. At that point, the music felt so different that I couldn’t understand it. I also could not find meaning in the drugs, violence, and the misogyny. These lyrics that I perceived to be abusive, embellished, and degrading did not agree with how I was raised to respect others and myself. I was fifteen and longing for the hip-hop from the late ‘80s-early ‘90s, or the “golden era” of hip-hop.

That same freshman year of high school, my oldest brother, Matt, who had just graduated from college, joined the Catholic Worker Movement and moved into the St. Joseph House in New York City. This was the first I had ever heard of the Catholic Worker Movement or Dorothy Day. But I did not give it much thought at the time because it did not seem pertinent to my life. When I was a sophomore in high school, though, I broke my foot and missed the soccer season. It was a long four months of recovery, as I grew bored and had much more time on my hands. So I took the time to learn more about the Catholic Worker Movement and its radical Christianity. I remember being transfixed by this clear vision of justice and by the unapologetic political nature of the ideas. It began a slow process within me as I began to understand social justice at a deeper level and in the context of a growing visceral awareness of oppression in my everyday experience.

When I graduated from high school, I attended Loyola University Chicago, a Jesuit Catholic University, and during my freshman year, I met one of my best friends, Chris. Chris was a hip-hop fan. He loved Kanye West.

Chris introduced me to the music of a young guy from Chicago named Lupe Fiasco, a devout Muslim from the Westside. I was intrigued. Then Lupe released his first album when I was a junior. It was like the moment that I first heard “Microphone Fiend.” It spoke to me. Lupe’s album Food and Liquor spoke of social issues in a language that resonated with my Catholic upbringing and my understanding of the Catholic Worker Movement. Lupe was “it” for me for the next two years. He represented what I wanted to see from people in my generation—a focus on justice that superseded everything else.

___________________________________________

Oppression is more than an event… Therefore, social justice must likewise go beyond action and become a state of mind, a lens on the world, a way of being… Hip-hop is more than the action of making music. It is a lifestyle born of resistance, it is a perspective and a preferential option for the poor.

___________________________________________

While at Loyola, I began to understand that social justice requires more than signing up for days of service, working at a soup kitchen, or even joining a Catholic Worker community. I began to realize that a commitment to justice requires a constant lens on the world: a lens that looks for all forms, both hidden and overt, of oppression. Oppression is more than an event, more than someone going hungry or being abused. Oppression is an attitude that we each carry but of which we are often unaware because it is part of our normal behavior. It goes by many names and manifestations: racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia, to name a few. These attitudes are so insidious that even though we may consider ourselves to be allies and advocates of the oppressed, in reality, many of our behaviors reinforce oppressive structures because these behaviors and structures seem so normal, common, and harmless. Therefore, social justice must likewise go beyond action and become a state of mind, a lens on the world, a way of being. This is when I began to realize that hip-hop also goes beyond the action of making music. It is a lifestyle born of resistance, it is a perspective and a preferential option for the poor.

It wasn’t until I met Eric, my partner with Rhymes and Reasons, that I fully began to appreciate hip-hop for what it is. I had experienced socially conscious hip-hop and enjoyed it, but Eric helped me to understand that, even if a song was not overtly focused on social justice, it was a subtle act of resistance.

Continue reading on next page…

Unbound Social