Let’s focus on nonviolence! I am encouraged by the news out of the 221st General Assembly of the PC(USA). The assembly decided that we need to continue our church-wide discernment process about peacemaking, and it sounds like there was some very good discussion around nonviolence in the peacemaking committee. While it will be helpful for presbyteries to consider all five of the affirmations put forward by the Advisory Committee on Social Witness Policy, it may be even more productive if we focus our attention on nonviolence in the coming years of peace discernment.

To this point, the discernment process has been extremely beneficial to the few who have been involved. The PC(USA) has put together some great materials that have laid out the history of our church’s engagement in peacemaking and given many options for moving forward. I attended a gathering for colleges that was packed with leading scholars in the field and the college where I teach, Monmouth College in Monmouth, IL, followed up with some lunch discussions for students, faculty, and staff based on study materials produced for the process. The timing couldn’t have been better; we were just starting our own peace and justice program, and these discussions tied nicely to that process.

___________________________________________

Because I cannot embrace either the just war doctrine or an absolute pacifism, I call my own view a pragmatic pacifism.

___________________________________________

If I have one critique of the process and materials it has produced so far, it would be that they are a little too diffuse. I read with interest the excellent, twenty-nine page report sent to GA, but I’m a geeky peace professor. I wonder if the process is suffering a little due to issues around practicality and packaging, and I think we have a golden opportunity to address these issues while considering the most promising and important topic in peacemaking: nonviolence.

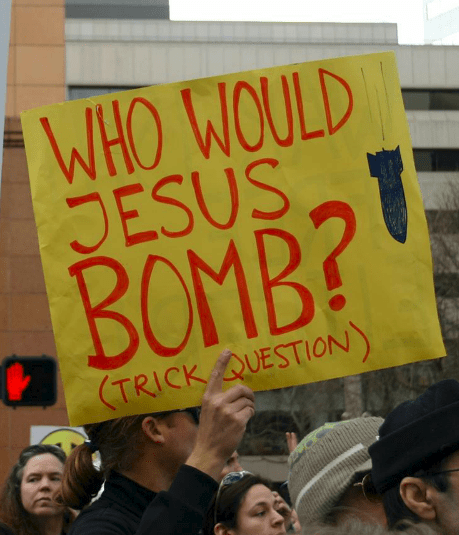

Perhaps such a focus could move us beyond a moribund debate that pits pacifism against just war. In fact, both of these positions were developed in Christian tradition to limit warfare and violence. Just war sought to set out clear criteria under which war could be engaged morally. Chief among these were the criteria that war should be defensive and that violence in war should never be excessive. Pacifism, on the other hand, sought to purify the church of the violent ways of the world and claimed that war could never be morally justifiable. Often Christian pacifism has led to a retreat from public life altogether, since violence and war seem almost inevitably to flow from politics. For this reason pacifism never resonated very well in the Reformed tradition, since one of the core values of our tradition is a public witness to social righteousness.

Because I cannot embrace either the just war doctrine or an absolute pacifism, I call my own view a pragmatic pacifism, under which one can affirm the need for public engagement and the often-resultant requirement of physical coercion in policing efforts but still deny that violence and war are ever morally justifiable. However, I must admit that every time I share this idea publicly, I’m accused of splitting hairs, and some refuse to see the difference between this view and just war. In reality, just war seems to me an untenable position after Dresden and Hiroshima (which killed any notion of proportionality or non-combatant distinction) and in an age of terrorism, “preventative war,” and robotic weapons (which stretch the very meanings of just war terms like competent authority, last resort, and just means). Some have argued that the just war doctrine has slipped into a position more accurately referred to as “war is hell.” [1] Here the breakdown of just war principles is acknowledged and moral boundaries of war are sought on a case-by-case basis.

___________________________________________

This debate between pacifism and just war is long and gets us into lots of difficult and sticky arguments. Nonviolence, on the other hand, might give us the foothold we need to make a public witness against violence and warfare without having to place our bets on either side of the debate.

___________________________________________

As you can likely see, this debate between pacifism and just war is long and gets us into lots of difficult and sticky arguments. Nonviolence, on the other hand, might give us the foothold we need to make a public witness against violence and warfare without having to place our bets on either side of the debate.

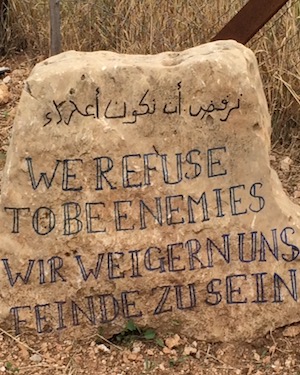

I have defined nonviolence as “a method by which conflict can be addressed and perhaps even inhabited without recourse to violent coercion. Nonviolence under this definition is an active engagement in conflict and is often used to address imbalances of power.” [2] Nonviolence finds its fullest expression in the classical examples of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., but it can also be applied to situations as varied as domestic conflict, bullying in schools, church conflicts, local politics, opposing tyrants, and even foreign occupation. The PC(USA)’s peace discernment materials have rightly extolled the virtues of nonviolence and cited the recent scholarship that is proving its effectiveness. [3] The beautiful thing about nonviolence is that it allows us a moral way in which to engage in conflict – not to side step it, not to suppress it in the name of peace or reconciliation – but to engage in it. Nonviolence allows us to confront our differences, to oppose injustice, and to right wrongs, all while honoring the dignity and value of the opponent.

Of course, when looking for examples of how to practice nonviolence, we need not look only to the classical heroes of nonviolence. We have heroes and heroines in our own midst. Recent news about the U.S.–Mexican border brings to mind John Fife and other founders of the sanctuary movement, as well as their successors like Allison Harrington, the members of Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, and the volunteers of No More Deaths.

___________________________________________

Of course, when looking for examples of how to practice nonviolence, we need not look only to the classical heroes of nonviolence. We have heroes and heroines in our own midst.

___________________________________________

Perhaps we can even point to the actions of the 221st General Assembly for resource and inspiration in their decisions to divest from companies complicit in disproportional violence against Palestinians. Whatever one thinks about the strategic effectiveness of these moves and however much work lies ahead in helping our Jewish and Israeli sisters and brothers to understand these actions, one cannot deny that this Assembly took bold, nonviolent, direct action and a profound public witness against oppression and violence. Surely, a great deal of our continuing peace discernment process will be focused on interpreting these actions and their effects.

This ongoing process of divestment and all of the debates and discussions that will inevitably come with it will certainly lead to what we higher-ed people like to call active learning. And perhaps this sort of active learning could be extended in our peace discernment process. Presbyteries could not only prayerfully and thoughtfully consider the five affirmations from the “Risking Peace” report, but could also redouble their efforts in conflict transformation training and consensus building. Congregations could not only continue discussing various options for peacemaking, but complement that discussion with action, reaching out to local schools offering the tools of nonviolence to address bullying. Perhaps if such seeds are planted, the whole PC(USA) could move past moribund debates and policy statements and further engage in active experimentation with nonviolent methods.

This ongoing process of divestment and all of the debates and discussions that will inevitably come with it will certainly lead to what we higher-ed people like to call active learning. And perhaps this sort of active learning could be extended in our peace discernment process. Presbyteries could not only prayerfully and thoughtfully consider the five affirmations from the “Risking Peace” report, but could also redouble their efforts in conflict transformation training and consensus building. Congregations could not only continue discussing various options for peacemaking, but complement that discussion with action, reaching out to local schools offering the tools of nonviolence to address bullying. Perhaps if such seeds are planted, the whole PC(USA) could move past moribund debates and policy statements and further engage in active experimentation with nonviolent methods.

Let’s focus on nonviolence, take action, and see what we learn.

_______________________________________________________________

[1] See Daniel A. Dombrowski, Christian Pacifism, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991).

[2] Daniel J. Ott, “Nonviolence and Moral Equivalency,” American Journal of Theology and Philosophy, Vol. 35, No. 2 (May 2014), pp. 173-174.

[3] Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011). Chenoweth and Stephan have compiled data over a one-hundred-year span concerning three types of resistance campaigns: antiregime, antioccupation and secession campaigns. The bottom line of their findings “is that between 1900 and 2006, nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts” (7). Furthermore, because nonviolent movements depend on broad-based participation for their success and create constructive responses to conflict, they are much more likely to result in stable and nonviolent political structures.

AUTHOR BIO: The Rev. Dr. Daniel J. Ott serves Monmouth College as assistant professor of religious studies and director of the college’s Peace, Ethics and Social Justice Program. Ott’s scholarship has been focused on community and communitarianism, and peace and nonviolence. He’s the author of several journal articles and review articles including his most recent, “Nonviolence and Moral Equivalency” published in the American Journal of Theology and Philosophy.

Read more articles from GA221: The Aftermath!

Unbound Social