Aaron Stauffer is a student at Union Theological Seminary, New York, coordinator of the Student Christian Movement – New York City, and Associate Director, Religions for Peace.

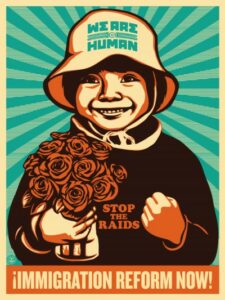

The intersection of citizenship and immigration is finally coming to the fore of national conversations. President Obama in his State of the Union message forcefully addressed immigration. On its heels was the Group of Six’s immigration reform bill. Pieces in The New York Times[1] and The Nation[2], on immigration and workers’ rights and deportation and detention halts (respectively), also stand out as worthy markers.

Our churches stand to benefit from engaging in this wider discussion, which addresses who decides what citizenship means, to whom it is extended and how these benefits are realized. In essence, this covers who you think your fellow citizen is, who isn’t, and why or why not?

Already, we can say this conversation includes the separation of families. In a pastoral letter to the PC(U.S.A.) Stated Clerk Gradye Parsons recounts[3] the birth of a grandchild. This joyous family event is harshly juxtaposed to the reality that the Parsons family enjoys a unity and safety that other families currently do not enjoy. I, along with Parsons, maintain that current U.S. immigration policies are destroying families. Families’ safety and unity pivot around a certain notion of citizenship.

___________________________________________

Today’s undocumented immigrants live in fear of deportation, of being separated from their families, and of worker and labor abuse…about 300 immigrants are in solitary confinement any given day, part of a vast population that helps sustain the private and public prison complex.

___________________________________________

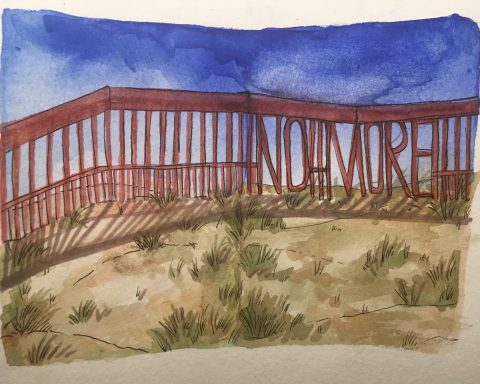

The militarization of the immigration system also has chilling effects: abrupt and sweeping raids conducted by U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE), indefinite detentions with no family contact, increased fencing that forces crossers out into danger of death in the desert. As one City Council member of El Paso maintains[4], it is less of a system to protect our nation than it is a system of privilege and oppression maintained through rights extended or denied.

Today’s undocumented immigrants live in fear of deportation, of being separated from their families, and of worker and labor abuse. A recent article documents that about 300 immigrants are in solitary confinement any given day, part of a vast population that helps sustain the private and public prison complex. [5] United States citizenship is seen as the basic protection against those dangers. Without the protection of some path to citizenship, workers’ rights to safety and dignity, much less self-determination through unionization, have little legal reality.

The Sanctuary movement of the 1980’s started with the desire to protect people fleeing death squads in Central America from deportation back to their countries of origin. In the Guatemala and El Salvador of that time, citizenship gave no protection from dictatorial regimes supported by the United States. Speaking out in that extreme situation, a brave minority of congregations were led to challenge immigration law, with support from the Presbyterian and Lutheran denominations. This was at the same time a statement about our own citizenship as entailing the defense of family safety and individual dignity from arbitrary political decisions. Our citizenship depends upon respect for human rights, including those of asylum seekers and refugees in our midst.

The Sanctuary movement of the 1980’s started with the desire to protect people fleeing death squads in Central America from deportation back to their countries of origin. In the Guatemala and El Salvador of that time, citizenship gave no protection from dictatorial regimes supported by the United States. Speaking out in that extreme situation, a brave minority of congregations were led to challenge immigration law, with support from the Presbyterian and Lutheran denominations. This was at the same time a statement about our own citizenship as entailing the defense of family safety and individual dignity from arbitrary political decisions. Our citizenship depends upon respect for human rights, including those of asylum seekers and refugees in our midst.

Yet, in a less prophetic vein, justice-oriented people of faith might do well to realize that immigration reform may be possible in the near future primarily because of changes in political as well as economic interests served. The Latino vote arguably carried the 2012 election. More visas granted can lead to further development in high-tech and/or agricultural industries, depending on the classifications favored.

These dynamics help people view reform as right and good for the country, opening the door for our churches to engage people – both those who hold idealistic views and those who do not – on the state of our democracy. The church’s mission of prophetic justice sometimes is carried through pragmatic avenues.

As a Christian on the left of the debate, I ought to be able to engage with conflicting democratically held values, to recognize how immigration reform can be both politically strategic and welcoming of the neighbor, to argue that it is both economically smart and what Jesus calls us to do. To do this, I have to engage others on their own terms, and then help them to see how their political and economic interests relate with my faith values of prophetic justice. Sometimes I may be over-focused on what I view as the prophetic message: policy smarts and fiscal issues aside, I am called to the side of the oppressed.

This can blind me to a basic core of democracy captured through conversational exchange on competing images of what would lead to well being for all. For example, some oppose immigration reform because they believe it means more downward pressure on wages, or more burdens on a poorly funded social service system; both justice arguments as well. I am suggesting that we acknowledge what we do every day when we meet people of competing opinions: we engage them on their terms and help them see our own point of view. But this does not mean that the church as a force for justice ought to disengage from the citizenship/immigration issue.

Churches have always played a role in establishing community. Social movements such as Abolition, Women’s Rights, Civil Rights, and now Gay rights are finding that religious folk have consistently stuck around in the fight. Our faith in God’s love to welcome the stranger keeps us mindful of our role in the immigration discussion. The difficulty of this conversation is the fine separation between contingent and essential rights: we have forgotten that we set up this notion of citizenry to meet specific communal needs in the first place. Our faith calls us back to the deeper recognition of how human dignity surpasses citizenship and how we are to reform our policies around this tension.

Churches have always played a role in establishing community. Social movements such as Abolition, Women’s Rights, Civil Rights, and now Gay rights are finding that religious folk have consistently stuck around in the fight. Our faith in God’s love to welcome the stranger keeps us mindful of our role in the immigration discussion. The difficulty of this conversation is the fine separation between contingent and essential rights: we have forgotten that we set up this notion of citizenry to meet specific communal needs in the first place. Our faith calls us back to the deeper recognition of how human dignity surpasses citizenship and how we are to reform our policies around this tension.

About the Author

Aaron is a student and organizer interested in identity, the church and activism. Currently in his second year of the MDiv program at Union Theological Seminary (NY), Aaron balances being the local coordinator for the Student Christian Movement – NYC, where he works to connect, agitate and activate young progressive people of faith, with the educational and interfaith advocacy work he does as the Associate Director for Religions for Peace USA.

NOTES:

[1] New York Times Editorial, “Immigration Reform and Workers’ Rights” http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/21/opinion/immigration-reform-and-workers-rights.html?_r=0

[2] Aura Bogado, “Why Won’t Obama Halt Deportations?” in The Nation http://www.thenation.com/blog/172871/aura-bogado-why-wont-obama-halt-deportations#

[3] Gradye Parsons “A Pastoral Letter from the Stated Clerk on Reuniting Families” http://www.pcusa.org/media/uploads/oga/pdf/0221_reuniting_families_act_press_release.pdf

[4] Veronica Escobar “Gridlock on the Rio Grande” New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/11/opinion/gridlock-on-the-rio-grande.html

[5] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/us/immigrants-held-in-solitary-cells-often-for-weeks.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20130324&_r=1&pagewanted=all&

Unbound Social