Content Warning – disturbing descriptions of violence inflicted on children.

You may have seen this debate floating around the interwebs over the past few weeks in the wake of the executions of Brandon Bernard and Alfred Bourgeois.

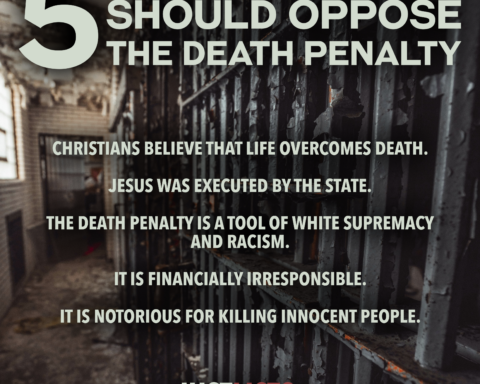

I didn’t wade into the debates; I knew where I stood. Like 39% of Americans according to a 2018 Pew poll, I oppose capital punishment in all cases. There was something especially cruel about state sponsored executions throughout Advent, the season when Christians await the birth of one who would die by state sponsored execution.

But a New York Times article by Elizabeth Bruenig, entitled “The Man I Saw Them Kill,” offered a piercing invitation to question my convictions. She is brutally honest about her experience bearing witness to the death of Alfred Bourgeois, who committed the kind of offense that can only be described as “cruel, senseless, and depraved.”

In 2002, Alfred Bourgeois “systematically tortured, sexually and physically abused his two-year-old daughter, culminating in her murder by ‘grabb[ing] her by the shoulders and slam[ing] the back of her head’” into the cab of his tractor trailer.

What did you feel in your body as you envisioned that sentence? I felt disgust and anger radiating from the pit of my stomach into my chest and through my arms until my hands actually began trembling. This is an embodied response. Arguments against the death penalty tend to be academic, philosophical, moral, appealing to our rational minds, our intellect, about what the value of a life ought to be. It’s easier to defend the condemned on legal and moral ground, searching for signs of repentance, remorse, or maybe even innocence. It’s harder to think about bodies. But victims of murder and their families have also experienced a grave injustice, and to refuse to pay attention to our visceral reaction is to erase the horrors inflicted upon people who suffer violence.

Bruenig, a death penalty abolitionist, describes the tension between this embodied response and what we believe to be true:

“In the purest and highest reaches of my spirit, I detest the idea of killing. And yet the impulse to erase from the earth every trace of a crime as monstrous as Mr. Bourgeois’s still arises in me, at times, pitting my emotions against my intellect. On some irrational level, it occasionally feels not only appropriate but also crucial, urgent. Some would say this is proof that execution satisfies a natural impulse, and a good deal of human history supports their claim. When I arrive on the brink of agreement, a favored verse from Jeremiah echoes in my thoughts: ‘The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: Who can know it?’ I don’t credit these impulses with any righteousness, but they persist nevertheless.”

So, is it true that you can’t be a Christian and support the death penalty? Are our arguments for its abolition rooted in detached, lofty philosophies that have the potential to ignore the embodied suffering of victims on earth?

There aren’t many 21st century ethical dilemmas that are so obviously spoken about in the Bible. But from Genesis to the Gospels to the early church, biblical examples of the death penalty abound. Where do we begin? My answer to this, like any typical Sunday School answer, is Jesus.

We see Jesus directly intervene during an impending execution in John 8, when many men bring a woman caught in adultery before Jesus. The Law couldn’t be any clearer; her just punishment was death by stoning. Jesus takes a moment, writes something on the ground, then stands back up and famously says “Let anyone among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.”

There’s a phrase at this moment in the story that’s often left out of translations: The leaders, being convicted by their conscience, went away one by one.

Being convicted by their conscience. We don’t know what Jesus wrote on the ground, but we know the effect was immediate and powerful. The men felt whatever Jesus had said to them. Whatever Jesus wrote convicted them, stirred their conscience, and led them to turn around, to literally repent. Paying attention to their own embodied response to whatever Jesus wrote on the ground guided their next actions.

The Supreme Court in 1972 recognized that the death penalty was disproportionately and systematically being applied to low income, people of color. The death penalty in the United States is no less “freakish” than it was in 1972. It is no less racist, classist, and ableist when the Supreme Court ruled it “cruel and unusual.” The death penalty is still a “flawed, expensive policy, defined by bias and error.” In Bryan Stevenson’s TED talk, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative invites us to imagine a world Germany where a death penalty, using it disproportionately against the Jewish community, especially those who commit crimes against Christians. And yet in the United States you’re 11 times more likely to get the death penalty if the victim is white than if the victim is Black, 22 times more likely to get it if the victim is white and the defendant is Black.

Bryan Stevenson speaks to this: “The question we need to ask about the death penalty in America is not whether someone deserves to die for a crime. The question is whether we deserve to kill.”

So we ask again: is it true that you can’t be a Christian and support the death penalty?

Just a few days after the woman was almost stoned, Jesus himself would be crucified, a death sentence executed by the state. Here, we have to be clear. Jesus’ death is not salvific. The cross did not save us. The meaning of Jesus’ death has been theologized and philosophized for two thousand years; no state execution has been more abstracted from reality.

Imagine necklaces with electric chair pendants, tattoos of gallows, or Pinterest boards filled with images of an electric chair overlayed with inspirational messages like “It was love, not straps and electrodes that kept Jesus bound to the electric chair!”

If The Passion of the Christ did anything, it was to remind us about the physical, brutal reality of the cross. Instead, imagine Alfred Bourgeois on a death bed, an intravenous line in his arm, pentobarbital pumped into his body, his jaw and mouth gaping open gasping for air, belly convulsing rhythmically for more than 20 minutes.

What did you feel in your body as you envisioned that sentence?

It’s okay to let yourself feel what you feel. We need to cultivate an embodied response to the horror of the death penalty, not rationalize our way to abolition.

Jesus not only stirs the convictions of our individual consciences. He also embodied radical witness against the calculated power of the state. This is good news. It is good news that death does not save us, that we can still repent, turn away from our most evil impulses. It is good news that Jesus unveiled death as the state’s ultimate weapon of coercion.

Good news is embodied, stirring us to move, to create, and to protest. Good news is breaking in. Thanks be to God.

Emily Wilkes (she/her/hers) is a candidate for ordination in the PC(USA). Her vocation lies in the intersection of ministry, farming, writing, and activism. A graduate of Davidson College, she was awarded a Lilly Fellowship to work in a small, politically-engaged church in Washington DC. She then served as a two-time Young Adult Volunteer: first as the Farm Steward at Ferncliff Camp and Conference Center in Little Rock, Arkansas, then as a teacher at the School for the Deaf in Moyobamba, Peru. After completing her Masters of Divinity at Princeton Theological Seminary, she began working at Interfaith-RISE, a refugee resettlement agency in New Jersey, as the director of the Refugee Farm and Food Sovereignty program.

Unbound Social