This reflection for common ground was written as a part of the Ignatian Solidarity Network’s Fall Call for Immigration Reform.

Texts:

Our God is a dreamer.

Joseph’s life has been turned upside down in the last few months. What seemed at first like his dreams coming true turned out to be a life-changing, transforming, counter-cultural opportunity to follow God. He stands by his woman, he travels with her to participate in the census, and his son is born – amidst animals and hay. In pursuit of God, Joseph finds a family, an unusual and unpredictable family, perhaps a different version of what he had always dreamed.

And then Joseph hears from God in his dreams again. The requests are no easier this time. Pack up your new family, flee in the night, and go to live in Egypt – a place he has never been, a place he has right and reason to fear, because what is taking place in his homeland gives more cause for fear. So Joseph does what God asks him to do, living for years as a refugee, an immigrant, a foreigner, all to outlive and outwit those who would harm his child. God comes to him again in a dream to send them home, but they come home to find they have to make their home in a new town to stay out of harm’s way.

___________________________________________

When our dreams are difficult, when our dreams ask more of us than we think we can give, when our dreams even ask us to do something illegal – how do we know if the dreams come from God?

___________________________________________

God comes to Joseph in his dreams. Joseph’s dreams have to change to follow the voice of the God he has heard. He has to adjust his vision and see the world differently, to cross boundaries he would have previously thought impossible – all to follow God.

We all have dreams. For people of faith, much of the challenge to is discern which dreams come from God and which don’t. I can’t imagine, particularly with what his dreams asked of him, that it was easy for Joseph to know – really know – that it was God who was speaking to him. When our dreams are difficult, when our dreams ask more of us than we think we can give, when our dreams even ask us to do something illegal – how do we know if the dreams come from God?

For many, college is a time of dreams – what are yours? What do you dream of? How can you tell when those dreams are your dreams and when they are God’s? What is the difference?

Dreamers come in all shapes and sizes, but lately, the dreamers in the news are students – some in college, some even younger – whose parents brought them to this country with a dream. They do not have legal immigration status, and yet many only know American culture and only speak English. Despite fear of deportation, they still dream that they can get an education, that they can fulfill their parents’ dreams, that they can fulfill God’s dreams for their lives.

In 2012, approximately 3 million students graduated from high school. One out of forty-two of those students was unable to pursue higher education because of their immigration status (source and source). Their dreams are dying.

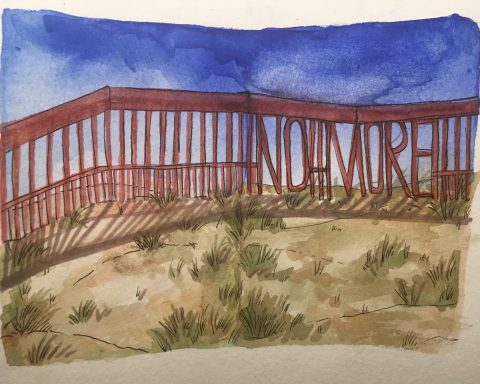

But there is hope. The DREAM act is still a real possibility. It would allow a path to citizenship for students brought by their parents and seeking a higher education. This idea has been stalled again and again in the legislature. In the mean time, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program has allowed many young adults to pursue work or education without the fear of deportation (source). The Senate has passed a large immigration reform bill and is waiting for the House to take up the issue, something that has been delayed countless times. People from across the political spectrum, people from a variety of faiths, have begun to see these dreams and to understand what will happen if and when these dreams die. It is time to ask that our government enact humane immigration reform and changes that will protect families and immigrants. It is time to provide a path to citizenship and allow for the rights and due processes of our government to be available to all those on our soil (Human Rights Watch’s version of humane reform can be found here).

Why, as Christians, should we be worried about this? Why, as people of God, is it incumbent upon us to speak up and out, to seek change, to protect people?

Because God is a dreamer too.

My daughter has this great book – the kind I’m huge sucker for – called God’s Dream. It’s written by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, famous for his work for reconciliation in South Africa. This darling little book, complete with rainbows and tears, describes how God’s dream is for all God’s children to live as family, even with all our differences. I read it to her in hopes that this dream lodges itself in her little heart, so that as she grows, she may always seek God’s dream.

My daughter has this great book – the kind I’m huge sucker for – called God’s Dream. It’s written by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, famous for his work for reconciliation in South Africa. This darling little book, complete with rainbows and tears, describes how God’s dream is for all God’s children to live as family, even with all our differences. I read it to her in hopes that this dream lodges itself in her little heart, so that as she grows, she may always seek God’s dream.

This little book points to something that I know to be true from the God I have experienced and the God I have encountered in Scripture. God’s dreams for each of us have no boundaries. God’s dreams for each of us know no discrimination. God’s love extends to all, and we are asked to love in the same way. How do I know? Because God asked his people to never consider any ownership permanent, but to always see themselves as foreigners in God’s land. If that is true, we all have equal access to God’s love, God’s dreams, and even God’s land (Leviticus 25:23). God tells the chosen people to love the widow and the orphan and the stranger and the foreigner because God loves them (Deuteronomy 10:18). When we read the Bible, tradition after tradition, law after law, makes provisions for the care of the foreigner among us. And yet we build walls and fences, arguing over who is truly entitled to our resources. We focus on keeping people out rather than making dreams come true.

The very same God came to Joseph and sent him to a strange place with no more than a dream. The very same God enlivened the Spirit of the beloved Son, our Savior, who had no place to lay his head during his ministry. The very same God was revealed as Christ touched lepers, spoke with foreign women, healed the unclean, ate with the tax collectors, and crossed boundary after boundary after boundary. Christ followed God’s dream despite what religious and moral authorities said, despite what convention would have led him to do. And God’s dream became real in his life, death, and resurrection.

That very same dream continues to come alive today, as parents dream for their children and as children work hard to live into the dreams of their parents. That very same dream continues to come alive today, even as we struggle to figure out who should be in and who should be out of the borders of our country.

What can you do to make God’s dreams reality? Not just God’s dreams for you, but God’s dreams for someone else. What can you do to honor the life of Christ by making real the vast and inclusive love that he lived while among us? What can you do?

Gods dreams are not about “what’s in it for me;” in fact, it’s quite the opposite. When Joseph followed God’s dream, he did so for the sake of his son. When the people of Israel kept covenant with God regarding those in need, they knew it was not for their own benefit. Living into God’s dreams is about stepping out of our own dreams – out of our own needs – and making other people our people. Making their dreams our dreams.

Gods dreams are not about “what’s in it for me;” in fact, it’s quite the opposite. When Joseph followed God’s dream, he did so for the sake of his son. When the people of Israel kept covenant with God regarding those in need, they knew it was not for their own benefit. Living into God’s dreams is about stepping out of our own dreams – out of our own needs – and making other people our people. Making their dreams our dreams.

God is a dreamer. What are you dreaming?

Let us pray.

AUTHOR BIO: Rev. Abby King-Kaiser is a campus minister serving all the non-Catholics at Xavier University, a Jesuit University in her hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio. She is the mother of one with another along the way, who loves reading with her three year old. She tries to squeeze in some time to write now and again.

Unbound Social