I. His eyes wouldn’t stay shut.

They taped them shut,

and then they’d just pop open again …

Initially, it seemed like small talk on a typical Sunday afternoon. That, at least, is what I imagined when I sat down at a round table with Treshawna Williams, LaChelle Rice, and Phyllis Scott in Reid Chapel, just outside the main sanctuary of the First & Franklin Presbyterian Church, in the Mt. Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore. It was a little after 2 p.m. on March 24, 2019. Our church was preparing to host a community-wide concert to raise awareness about the violence in our city. So it was that Treshawna, Phyllis, and LaChelle were there, in Reid Chapel, preparing to speak in a traditionally white church. They were united by a story of loss: each had lost a child to the violence in Baltimore, Treshawna just a few months before.2

If the concert that followed was powerful (and it was), the testimonies of these three women were inexpressibly beautiful and to the same degree painful. Yet what I heard before the concert continues to haunt me: “His eyes wouldn’t stay shut. They taped them shut, and then they’d just pop open again. I think he was seeing something beautiful, that’s why his eyes wouldn’t stay shut.” “He was messed up,” Phyllis said over and over, just shaking her head, like she was trying to shake away an image that haunted her at that moment, shaking her head as if stung, shuddering as if she had suffered the gunshot herself. Another told how her family took care of her son’s body: trimming his fingernails, shaving him, washing him, dressing him, almost like a mother would do before sending her child to school … only, he wasn’t going to school. Or graduating. Or getting married. Or posing with their first child. Instead, the bodies of their children were being prepared for burial, for incineration.3

At one level, maybe this talk makes us uncomfortable because it is too true. But there is another possibility: if we think of these tender expressions as a longing, a call, and a plea for resurrection, or even more sharply expressed, as a call for an uprising of resurrection, for incarnation, for mending of the creational hoop, then I suppose we have begun to hear the true import of their testimony.

II.This Is Crazy

Brian K. Blount, New Testament scholar and president of Union Theological Seminary, Richmond, Virginia, believes that the story of resurrection isn’t only for Easter, but for a world typified by death: “In a world typified by death, killings, even high-profile killings, do not raise a transforming alarm. …What the purveyors of death notice is defiant life. It is resurrection that frightens them. …Only life can conquer death.”4 As powerful as Blount’s challenge is, a profound obstacle stands in the way of the kind of witness he imagines. Perhaps we could call it the cultural hermeneutic of white denial, that whiteness does not in fact exist. This sort of denial is endemic to the way we talk about race, violence, and the inequities of our nation.

In the planning for this assembly, this was a familiar comment: “What’s happening in Baltimore doesn’t reflect what’s going on in our communities. …” This, or something close to it, was a comment made frequently enough in the planning stages for this meeting that it deserves a firm rebuttal, not because it is unique but because it is commonplace and wrong.

At the risk of sounding glib, it is about Baltimore. Ours is a national church, a predominantly white church, and it is meeting in the heart of a majority black city, where Freddie Gray died as a result of police brutality in 2015.5 From 2015 through 2019, there have been 1,660 homicides in Baltimore, 348 in 2019 alone.6 That’s 55 deaths per 100,000 people, higher than the per capita rate of homicide in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, or Chicago. Alone, the raw numbers disguise the impact of the violence. In 2015, 93 percent of the victims were black. There have been around one thousand people wounded every year by gunfire. One person laments the carnage as a scourge of “hurt people hurting hurt people.”7

Even so, talking about this as an anomalous crime wave falling within the unique confines of the City of Baltimore fails to name the systemic and racial contours of the violence in our nation. It presupposes that highly segregated congregations of the suburbs and rural parts of America are, by definition, sane while Baltimore (and cities like it) are insane.

This gets harder to believe with each act of white terrorism. Consider the April 27, 2019, antisemitic attack on the Chabad Synagogue in Poway, California. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, Poway is 76.9 percent white. The pastors of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (majority white) where the white terrorist, John Earnest (nineteen-years old) worshipped, where his father was an ordained ruling elder, would not have seen themselves as actively racist, and would in all likelihood self-describe as antiracist. However, they do pride themselves on their orthodoxy. Indeed, Earnest’s pastors were not shocked by the racist ideas within his “manifesto”—they were shocked that Earnest was, by their standards, theologically coherent. OPC leaders believe that white supremacist views are incompatible with their doctrinal statements.8 Maybe, to explain this contradiction, some would say this outburst was an “anomaly”—limited to one person’s mental illness, unrelated to his apparent theological literacy.

W.E.B. Du Bois might see it differently. Seemingly isolated expressions of white racism “are not instances of ‘Europe gone mad’ but of Europe itself, ‘the real soul of white culture … stripped and visible today.’”9 Could it be possible that the madness of our city is only more visible here than it is everywhere else?

The history of the City of Baltimore, redlining (the practice of excluding majority black communities from financial resources10), corrupt policing, and starving public schools reflects a prevailing theology of white nationalism. Was the white church a “neutral” player in forming the social, economic, and political infrastructure of cities like Baltimore? Did the architects of segregation draw from the myth of white theological coherence? Amid such violent eruptions, Du Bois might see whiteness stripped of the pretense of being anything but ultimately and profoundly insane.

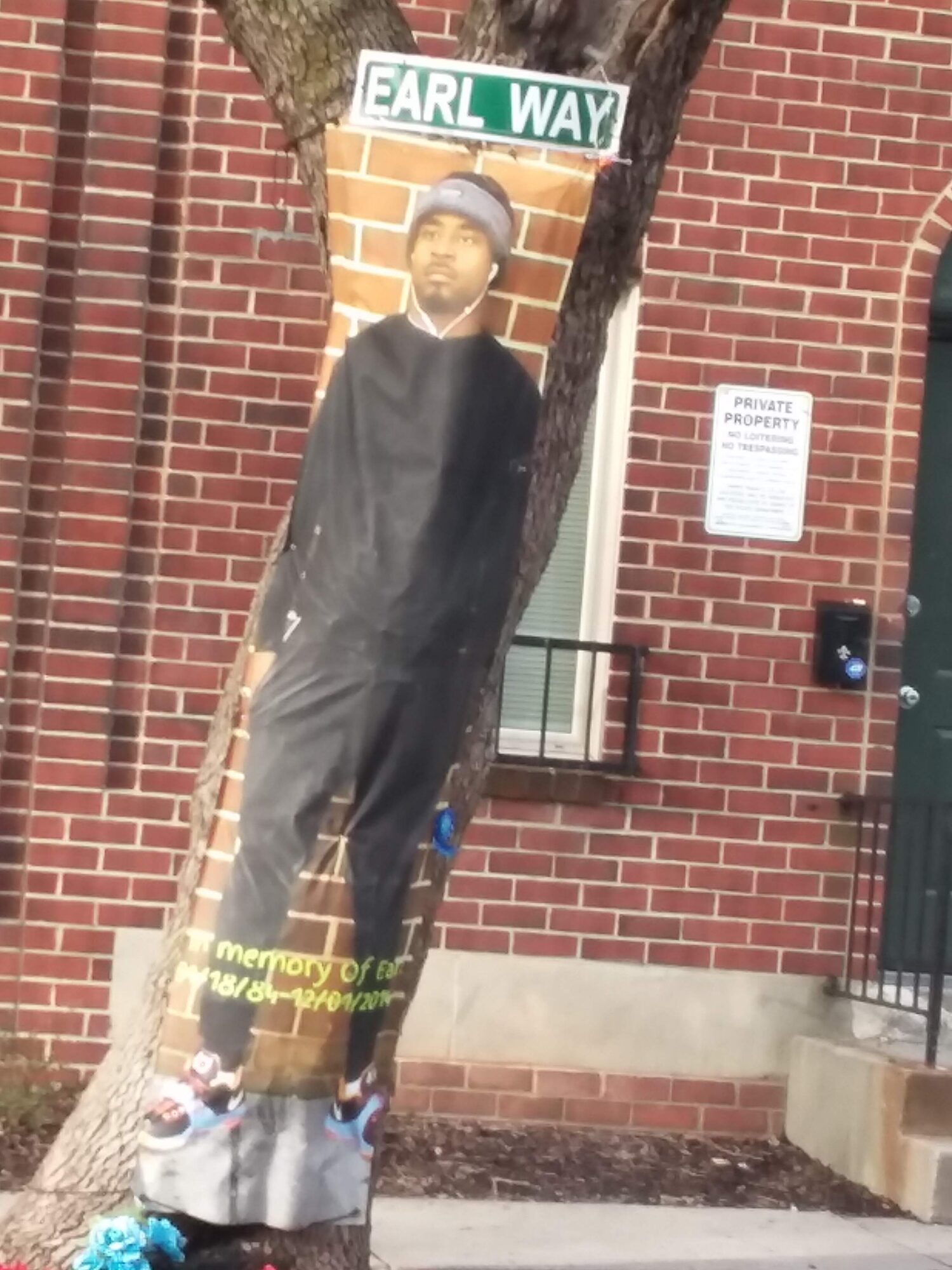

In November of 2019, as people from the community of Sandtown Winchester gathered to prepare a memorial for the shocking number of deaths they have witnessed, people kept saying, “This is crazy,” as in entire neighborhoods redlined again through the violence of denied funding of necessary social services and by a “war on poverty” that looks like a war on the poor. Will Tyler, whose son, Delante’ Tyler, was murdered in 2017 (he is survived by two children), takes me into his home, where, like many others, he keeps a memorial of photographs, family and friends, with his son at the center. He points to them, one by one: “He’s been killed. He’s dead. He dead. My son. These two are in prison. This one, he’s dead. He was killed a week ago, no—no four days ago.” Altogether, he counts thirteen people lost in three years.

Will relates the story of the loss of his son, Delante’ Tyler, with whom he was talking at the moment of the shooting: “I told him, ‘Get out of the store,’ cause I had a bad feeling and then I heard pop, pop, pop … and somethin’ in me knew it was Delante’ got shot. I dropped my phone right there,” he says pointing to a nearby playground, situated between the projects, the Gilmore Homes, just four blocks from where Freddie Gray lived. “I ran over to where he was, the store, and saw him there shot in the head. He died in my arms.”11

Lor Choc, twenty-one-years old, is a rapper and a local celebrity in her home neighborhood of Sandtown Winchester.12 Gunshots, she says, are “pretty much the same” as what she has always known.13 Sometimes, as she talks, she seems ambivalent about whether she is immune to the violence or not. But you hear it in her music, and in her own sense of shock at what has been lost: “Before my uncle was shot, we’d be at his house all the time, sharin’ a drink and relaxin’, but after he was killed it wasn’t the same. I still go over there, to see my cousins, but it’s empty now, it’s just empty, empty. Empty.”

In November, I hadn’t seen Phyllis for nine months, since the memorial concert in March, when she had recounted the loss of her son, Malcolm. Seeing me again, she locked onto me with the intensity of a person who has known too much pain to abide fools: “You don’t know what I been through! You don’t know! You don’t know!” Soon I would: “My son,” she says, “was shot, 23 times, 23 times! He lost his eye and his foot is really messed up. He’s not able to work and he has got a lot of anger and mental issues. PTSD? I really think so. …” I meet her son, Jay’Trelle, twenty-five-years old, a few days later, when I go to Phyllis’ home in Westport to donate some socks she plans to distribute to people in the community. I knock on the door. In answer, someone shouts, “It’s a white man! There’s a white man at the door!” I say, “I’m here to see Phyllis.” I hear Phyllis’ voice from inside. She opens the door, and her son limps out of the house. “Don’t pay any attention to him,” she tells me. “People ain’t crayons,” she says, calling after him. “He know better than that!” Jay’Trelle’s left eye is turned out, permanently twisted in blindness as a result of the shooting. “He lost that eye. He ain’t gettin’ that one back,” she says, almost as if speaking of a catalog of losses he has experienced as a result of the shooting. She thinks it was a case of mistaken identity.14

It is insane. Markell Hendricks, sixteen-years old, was another murder victim. He was the grandson of Dorothy Cunningham, a member of Baltimoreans United in Leadership Development, a leading grass-roots organization. As I attended the memorial, it struck me again, how incongruous our city: the funeral home where Markell’s services were held, was efficient, right on time. It felt like the bureaucracy of a well-oiled necropolis. Pictures of Markell were being streamed. There was an open casket. I confess I didn’t want to know him that way. So, I looked at the pictures. The smile. The teenage swagger. The promise. A decorated basketball was posed as a kind of centerpiece, as doll-like as a body embalmed for burial. There was plenty of parking at the funeral home. The building itself was in prime condition: no broken windows, no graffiti, plenty of parking, and it was expanding, with new additions—while around it, the neighborhood was dilapidated and collapsing. Funeral homes should be struggling to survive, not expanding their brands. High school graduates should be the crown jewels of Baltimore, not the doll-like products of its morticians.

Commissioners will, no doubt, enjoy the beautiful space of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. It seems so sane. But is it? Is it sane in the same way that the gleaming products of the mortician in Sandtown Winchester are? Seemingly aglow, but dead, dead, dead? At a community meeting in Edmundson Village (near where Taylor Hayes, seven-years old, was mortally wounded by gunfire in the summer of 2018), the newly appointed Police Commissioner Michael Harrison took questions from residents. Renee McCray pointed out the difference between Inner Harbor—where our assembly is meeting—and Baltimore’s distressed communities:

The lighting was so bright [in the Inner Harbor]. People had scooters. They had bikes. They had babies in strollers. And I said: “What city is this? This is not Baltimore City.” Because if you go up to Martin Luther King Boulevard [the demarcation between downtown and the west side] we’re all bolted in our homes, we’re locked down … all any of us want is equal protection.15

Was this just another version of redlining, only this time the line was blue?16

Indeed, victims of violence not only bear the burden of their loss alone, often with minimal support from police and social services, they have also become the targets of racist barbs from Washington D.C. The president of the United States, with the support of Fox News and hate-radio, uses dog-whistle phrases to stir up white nationalists, calling the city rat-infested, with the not-so-subtle call for racial extermination and so on—how can this General Assembly be anything but a moment of deep self-examination for us as a denomination? It is as if the church were to meet in New York City, following the September 11 attack. Would there be any question at all whether the meeting would be about New York City? Yet when the genocide taking place is a citywide lynching executed amid unapologetically racist attacks from Washington D.C., then it is a “local” issue, that “doesn’t speak to” our national narrative, much less our local ones. It is as if this question, this body-talk, is confined to Baltimore, as though the violence here were somehow anomalous rather than the tragically predictable outcome of historically systemic racism, inequity, and police brutality.

Our church adopted the Confession of Belhar but has not confessed its cooperation with systemic violence against people of color since the birth of the slave economy in 1619.17 Is it possible that this meeting, in a city scarred by the stain of racism, is the time and the place for us as a national body to repent of our complicity with racist powers?

In Baltimore, you will see unrest and uprising. It will be up to the assembly to determine how it will be a part of this historic moment.

III. Dead: A Relative Term

“The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, ‘Unbind him and let him go.’” (John 11:14)

Mostly, when we read this story, the raising of Lazarus is complete when Jesus commands Lazarus to come out of the tomb. But in John’s telling, it wasn’t a living person, but a dead person that came out, walking, however improbably, with hands and feet bound with graveclothes. The narrator deploys language with brutal honesty (“‘Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead four days’”) as well as with frightening audacity, evoking resurrection. Albeit unintentionally, artists and journalists seem to almost probe the Lazarus event, both its agony but also its power, through their investigations and interpretations. Baltimore journalist, Alec MacGillis, says that you can tell a lot about the politics of people by the different words they use to describe events surrounding Freddie Gray: “Some people … call them the ‘riots;’ some the ‘unrest.’ [Others always refer] to them as the ‘uprising,’ a word that connoted something justifiable and positive. …”18 Devin Allen, a Baltimore photographer who gained national recognition for his work during the riots, is in the latter group:

When most people think about the “ghetto,” they think of poverty, struggle, pain, violence, drugs. But for me, the word “ghetto” is so much more. When I look deep into my community, I see a beauty that is often overlooked and unappreciated. There are so many different aspects to an uprising: rioting, looting, cookouts, block parties, prayer circles, town hall meetings. The Baltimore uprising gave people like me a voice. Since the murder of Freddie Gray, my city has not been reborn, but it’s on its way.19

By meeting in Baltimore, the assembly has got in line with the crucified and at the same time is witness to Jesus’ calling the dead out of our national graves, painful and beautiful to behold. But resurrection, in John’s estimation, includes collaborative works of community, as together, we collectively become implicated in the story of Lazarus’ resuscitation unto resurrection.

IV. Raising the Dead

Because our church has worked to name whiteness in America, our liturgy sometimes becomes uncomfortably realistic as we attempt to craft liturgies that play a part in the determined preservation of uncomfortable truths about America’s violent history. Following the president’s comparison of his impeachment to a lynching, we incorporated this short litany into worship, adapting it from Michele Norris’ Washington Post column, “So You Want to Talk about Lynching?”20

One: So, you want to talk about lynching?

All: O God, we confess that we know too little about lynching.

One: A lynching involved a man or a woman, or sometimes a child, dragged from their homes, hauled out like lambs to be slaughtered.

All: O God, we confess that we know too little about lynching.

One: A lynching also involved a man (almost always a man) who had a rope or a rope that was ready with a noose. It had to be a coarse, heavy, corded rope.

All: O God, we confess that we know too little about lynching.

One: A lynching was an impulsive act, but the actual lynching itself took technique, skill; someone had to know how to find the tree suited to the work, a branch strong enough, high enough, to do the work.

All: O God, we confess that we know too little about lynching.

One: It took a lot of people to hold a lynching. Good people. People who taught Sunday school. People who looked the other way. Dedicated people. Nice people.

All: O God, we confess that we know too little about lynching.

One: According to the NAACP, 4,743 people were lynched in the United States from 1882 to 1968. 3,446 were black.

All: O God, we confess that we know too little about lynching.

One: No matter what, gravity always won.

All: O God, we confess that we know far, far too much about lynching.

Forgive us, O God, but not too quickly.

Forgive us, O God, but not too cheaply.

Forgive us, O God.

Removing the graveclothes of our racist history is not something that we can do alone, or with liturgies; maybe this is because many of us don’t realize that we are walking while bound in the graveclothes of whiteness. After all, everyone tells us we’re alive. However, the longer we sit with John’s account of the raising of Lazarus, the more difficult it becomes to tell who is really dead in this story: is it Lazarus, the dead man walking, or the onlookers, still acting as if death rules the day, while seemingly fully alive? Is “dead,” as Brian Blount suggests, a relative term?

The Reverend Dr. Phyllis Felton, the pastor of Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church and I met together, as she put it, to “break the ice” between our two congregations. Madison Avenue shares a history with First & Franklin Presbyterian Church. In 1848, the original First Presbyterian Church purchased a property for the black people who worshipped in the same building as whites but not as a body, not as a congregation. The oral history suggests that African Americans wanted to have a greater leadership role in the church. This was not to be. Instead, being a wealthy congregation, the white leadership of First Presbyterian Church decided to purchase a “substantial church” for their use.21

Today, we are hearing a call to come out, or we are together coming out of our complicity with whiteness as the ruling principality and power in America: “We’re pushing for the same thing,” Felton says of our two congregations. “We know our churches were born in the womb of racism. That’s not all we are, and we don’t need to stay there, but we do need to acknowledge that past.” Our buildings are on opposite ends of Madison Avenue, linked by a road but divided by a segregated history. We were invited to join the Madison Avenue Church in a Watch Night Service on January 31, 2019, 400 years after the birth of the slave economy. Seven adults and four children from the First & Franklin congregation gathered with about twenty or so adults and children of the Madison Avenue Church, which is currently located just off North Avenue, in the same zip code as Sandtown Winchester.

We broke bread, talked about what hope looks like for us, and worshipped together. It was a small gathering around a tomb that has been sealed for too many years. “We leave right at midnight,” she tells us. And then, comfortingly, “Sometimes we hear gunshots, but it’s okay. Don’t worry about that.”

We’re still at the beginning of this journey, but somehow that act feels like living; it is clear that whatever we’re about, it’s about community building, not simply church buildings. And it is also more than Baltimore, according to Felton: “I would think we would have something to say to this General Assembly. We are at a time in our nation and in our church when if anyone has a voice, it should be us.”

V. Lazarus Is Walking

When I sat down with Phyllis, Treshawna, and LaChelle, what I heard was body talk of the most profound kind. In a few minutes, we would walk into the main sanctuary for a memorial concert to those who had lost their lives to the gun violence in Baltimore. They would be speaking to an audience of nearly 300 people from across Baltimore. Over ninety-minutes, they told a rapt congregation of their experiences of loss, pain, misunderstanding, and hope. Corneilius Scott and Pam Stein of the Family Survivor Network use four prompts to help those impacted by the violence process their feelings: where I was when I found out; what I miss most; the big lie; and what comes next. Their responses to those prompts formed the heart of the service:

I miss his fat cheeks; I miss our talks late at night after I got home from work; he always used to cry out when he came home, “Ma, Ma? Where are you, Ma?” When I asked, “Why you yell out like that, when you know I’m home?” He told me, “Because I want you to know that I have arrived.” I will never forget that you have arrived.

Just ten days before his untimely death, Corneilius Scott shared that they had added another prompt to these four: “I want to introduce you to my son/daughter/brother/sister—using the present tense.” Scott explained that for survivors the present tense is gone. Perhaps, in a sense, what Scott was attempting to do was undermine the finality of the tomb with living testimony.

People of faith live under two obligations: we are called to speak truth to power and to speak the truth in love. And yet, so often, when we speak the truth to power, there is no love; and when we speak in love, there is no power. Treshawna, Phyllis, and LaChelle told us their truth in love and in power—and Lazarus is walking.

Endnotes

1. The author has served as the pastor of First & Franklin Presbyterian Church since June 2016. Before he came to Baltimore, he served as a professor of homiletics and worship at the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary, a PC(USA) school. He self-identifies as Alaska Native descendent (Athabascan) of mixed ancestry.

2. The Family Survivor Network (FSN) (a group that supports families impacted by the scourge of homicides in our city by providing, among other things, support groups, case management, art therapy, and fellowship opportunities) had been instrumental in bringing us together with these three courageous women. Pam Stein, clinical program director for FSN, is a licensed social worker and art therapist. Stein says that FSN deliberately chose to locate its office in the Sandtown Winchester neighborhood, just a few blocks away from where Freddie Gray lived and at the epicenter of the killings. The founder and executive director, Corneilius Scott, died unexpectedly on December 20, 2019. His son was a victim of handgun violence in August 2014. Pam relates that after Cornelius’ son, Ian, was assaulted, he had a conversation with God: “God, if my son survives, you have me.” His son survived. That experience moved Corneilius to become a dedicated advocate for victims of gun violence in Baltimore. This piece would not have been possible without the incredible courage, hospitality, and generosity of the FSN community. Read more about its work at https://www.fsnwork.org/.

3. Treshawna Williams, LaChelle Rice, and Phyllis Scott gave me permission to share their experiences.

4. Brian K. Blount, Invasion of the Dead: Preaching Resurrection (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), 23–4.

5. “Among the deaths at police officers’ hands that animated the Black Lives Matter movement in its early stages, Gray’s was uniquely ambiguous. He was not shot, as were Laquan McDonald in Chicago; Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; Tamir Rice in Cleveland; and Walter Scott in North Charleston, South Carolina. All that is known for certain is this: When he encountered the police officers, Gray—who had engaged in low-level dealing over the years— ran. When the police gave chase and tackled him, they found a small knife in his pocket and placed him under arrest. Gray was put in the back of a police van shackled and unbuckled, in violation of a new department policy. When the van arrived at the Western District’s headquarters, Gray was unconscious with a nearly severed spinal cord. He died seven days later.” Alec MacGillis, “The Tragedy of Baltimore” in The New York Times (12 May 2019), accessed on January 4, 2020, at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/12/magazine/baltimore-tragedy-crime.html.

6. The killings occur in the most distressed neighborhoods of Baltimore, with a narrow swathe of the City, Bolton Hill, Mount Vernon, and Inner Harbor nearly untouched. See “Baltimore Homicides” in The Baltimore Sun at https://homicides.news.baltimoresun.com/.

7. The statistics only tell part of the story, as Courtland Milloy reminds us: “Violence has a cumulative effect. A 10-year-old child growing up in the city’s most troubled neighborhoods has a decade of gun violence impacting his or her life—murdered and wounded friends, classmates, neighbors, relatives and strangers alike.” Courtland Milloy, “At One Church, Combating Neighborhood Violence Requires Prayer and Footwork” in The Washington Post (7 January 2020), accessed on January 8, 2020, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/at-one-church-neighborhood-combating-violence-requires-prayer-and-footwork/2020/01/07/f3119ec8-315d-11ea-91fd-82d4e04a3fac_story.html.

8. Julie Zauzmer, “The Alleged Synagogue Was a Churchgoer Who Talked Christian Theology” in The Washington Post (1 May 2019) accessed on January 4, 2020, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/religion/2019/05/01/alleged-synagogue-shooter-was-churchgoer-who-articulated-christian-theology-prompting-tough-questions-evangelical-pastors/.

9. W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of White Folk in W.E.B. Du Bois, ed., Writings (New York: Library of America, 1986) quoted in Martín Alcoff, Future of Whiteness, 140.

10. Antero Pietila documents the historical development of what became popularly known as the “black tax”—that is, the additional cost extracted from African Americans for inferior housing located in areas color-coded as “undesirable” by Federal housing authorities. According to their explanation, redlined neighborhoods exhibited “detrimental influences in a pronounced degree [with an] undesirable population.” Pietila concludes, “a two-tier lending industry was born. Banks served well-to-do white areas; blacks had to get financing from speculators at harsh terms.” Pietila uncovers a similar discriminatory process for Jewish communities. See Antero Pietila, Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 70.

11. Will Tyler’s stepson, Brandon (called “D”), eighteen-years old, was killed in early January 2020, next to his home and right near a memorial that was designed by FSN to draw victims together.

12. To hear Lor Choc, click on “Soul Cry” (2019) at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zcc6UClsUyA.

13. Quinn Kelley, “Lor Choc Rapper and Singer” in “Female Troubles: Episode 64” in The Baltimore Sun (23 January 2018), podcast accessed on January 8, 2020, at https://www.baltimoresun.com/audio/podcasts/bs-female-trouble-lor-choc-20180123-htmlstory.html.

14. Should you ever call Phyllis, her phone message is simply, “Mom.”

15. MacGillis, “The Tragedy of Baltimore” in The New York Times (12 May 2019).

16. Some say there are three institutions that are still strong in the city’s distressed neighborhoods: churches, grass-roots organizations, and gangs—not necessarily in that order. Notably, the police department isn’t often included as a positive force for change. There are some signs that this could be changing. Police Commissioner Michael Harrison describes the guiding philosophy of the Department: “My philosophy is that officers should be tough on crime, but soft on people.” Col. Sheree Briscoe of the Baltimore Police Department echoes these commitments: “Bring those to justice who violate the law but also address the phenomenon of crime through relationships and resources to address crime born of need. The juvenile population, for example, just wants to belong. When we learn of families in need, we point them to resources to assist them. The challenge becomes timely intervention.”

17. [“Confessing” refers here partly to the Book of Confessions, which includes the Confession of Belhar. Both predecessor churches sought to repudiate racism; a brief apology for slavery was made in 2001.]

18. MacGillis, “The Tragedy of Baltimore” in The New York Times (12 May 2019).

19. Devin Allen, A Beautiful Ghetto (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), xx.

20. Michelle L. Norris, “So You Want to Talk about Lynching?” in The Washington Post (23 October 2019), accessed on January 9, 2020, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/so-you-want-to-talk-about-lynching-understand-this-first/2019/10/23/c5a5fd2a-f5ae-11e9-ad8b-85e2aa00b5ce_story.html.

21. African Americans were not allowed to own property at the time, so the board of the First Presbyterian Church purchased and held it on their behalf. Its pastor, and the leaders of First Presbyterian Church, clearly viewed this gesture as progressive and liberal-minded. In retrospect, while well-intentioned, it was a part of the myth of white exceptionalism that has dominated (bound) white people in America since 1619. John H. Gardner Jr., The First Presbyterian Church of Baltimore: A Two Century Chronicle (Baltimore: First Presbyterian Church, 1962), 94.

The entire Epistles from Baltimore document may be found here.

Rev. Robert P. Hoch, Ph.D. is the pastor of First and Franklin Presbyterian Church in Baltimore.

Unbound Social