Scrawled on a page of my Choctaw Hymn book is the Choctaw version of Matthew 7:7,

“Hvsh asilhhakma, hvch ima he; hvsh hoyokmvt, hvsh ahayucha he; hvsh soko hakma, hvchin tiwa he oke.” Ask, and it will be given you; search, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened for you. (NRSV)

I wrote this as a mantra to remind myself that if I am going to recapture my language, I had to take action, make a conscious effort and not just hold onto the words and phrases that I know, but to truly become fluent as my Tinkba, those who came before me, were.

On the backside of the crude leather cover of my Choctaw Hymn book, I have drawn a picture of the people walking the Trail of Tears towards the hills of Southeastern Oklahoma. On the front, images representing the Choctaw names of my children: a Yellow Flower, Stars, a Red-tailed Hawk, and two mountaintops for my grandsons who live among their father’s people, the Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) in Idaho. These are reminders of why it is important for me to take action and pass on our language. Our language defines our familial and communal roles and who we are as a people. No longer are we forced to conform, but we have the choice to be who we are as indigenous people.

These are reminders of why it is important for me to take action and pass on our language. Our language defines our familial and communal roles and who we are as a people.

As a child, I grew up in a home where my parents spoke both Choctaw and English interchangeably. They made a conscious decision that English would be our first language so that my siblings and I would not have to experience the trauma of going to school and not knowing English. My mother often recounted the story of being at school and not knowing what the teachers were saying and how she cried until some of the other English-speaking Choctaw students helped her.

Some of my fondest memories as a child are when my grandmothers would come to visit or spend time at our home. Late in the night in our living room, or sometime early in the mornings around the kitchen table, I would hear them conversing in Choctaw. I now wish I had paid more attention to what was being said.

My maternal grandmother never attended school, so her primary language was Choctaw. She did, however, know some English, and I remember hearing her read the sign at a grocery store once while we waited in the car for my mother to come out. She pronounced each letter and said the words at the end. My paternal grandmother went to boarding school at the Wheelock Academy. She once told me about her experience there and how they were punished for speaking in Choctaw. If it was in a classroom, they were made to stand during class, or they would have their hands hit with rulers.

My paternal grandmother went to boarding school at the Wheelock Academy. She once told me about her experience there and how they were punished for speaking in Choctaw.

Unlike some of the more widely known boarding schools like Carlisle, Wheelock Academy was mostly Choctaw. My grandmother said that when they were alone in the rooms, they would speak Choctaw. But even then, she said some of the students would tell on them for speaking Choctaw. I often wondered why one would tell on another that is in the same situation. Were they instructed to do so or perhaps fearful of being associated with them if they were caught?

At church, we sang hymns in Choctaw, and even as late as my childhood, I remember that most of the worship and preaching was done in Choctaw. It’s ironic that the hymn books and the Bible used were ones translated by missionaries in the early 1800’s such as Cyrus Byington. Later, when boarding schools were run by the US government, our people were not allowed to speak or sing our own language.

The church I grew up in was once the center of one of the first communities established by the Choctaw after arriving in the new territory after the forced removal. It was named Oka Achukma (Goodwater) after a spring that provided cool, clear water even during the hottest and driest summer months. The people took care of the spring by keeping the leaves and sticks out of it and kept the opening clear where the spring ran into a nearby creek. The water was clear and cold, and as it drained into the creek, it would mix with the warm, silty water.

The church I grew up in was once the center of one of the first communities established by the Choctaw after arriving in the new territory after the forced removal.

I remember when our church would host weekend meetings we called conventions, and I remember people would walk down the trail to the spring with a dipper in hand to get a drink during the breaks. The trail leading from the road to the spring was a combination of rocks placed by hands long before my time and tree roots that had grown across the path serving as natural steps. The dirt was worn bare and made firm by the countless feet that had made this trek down to the spring.

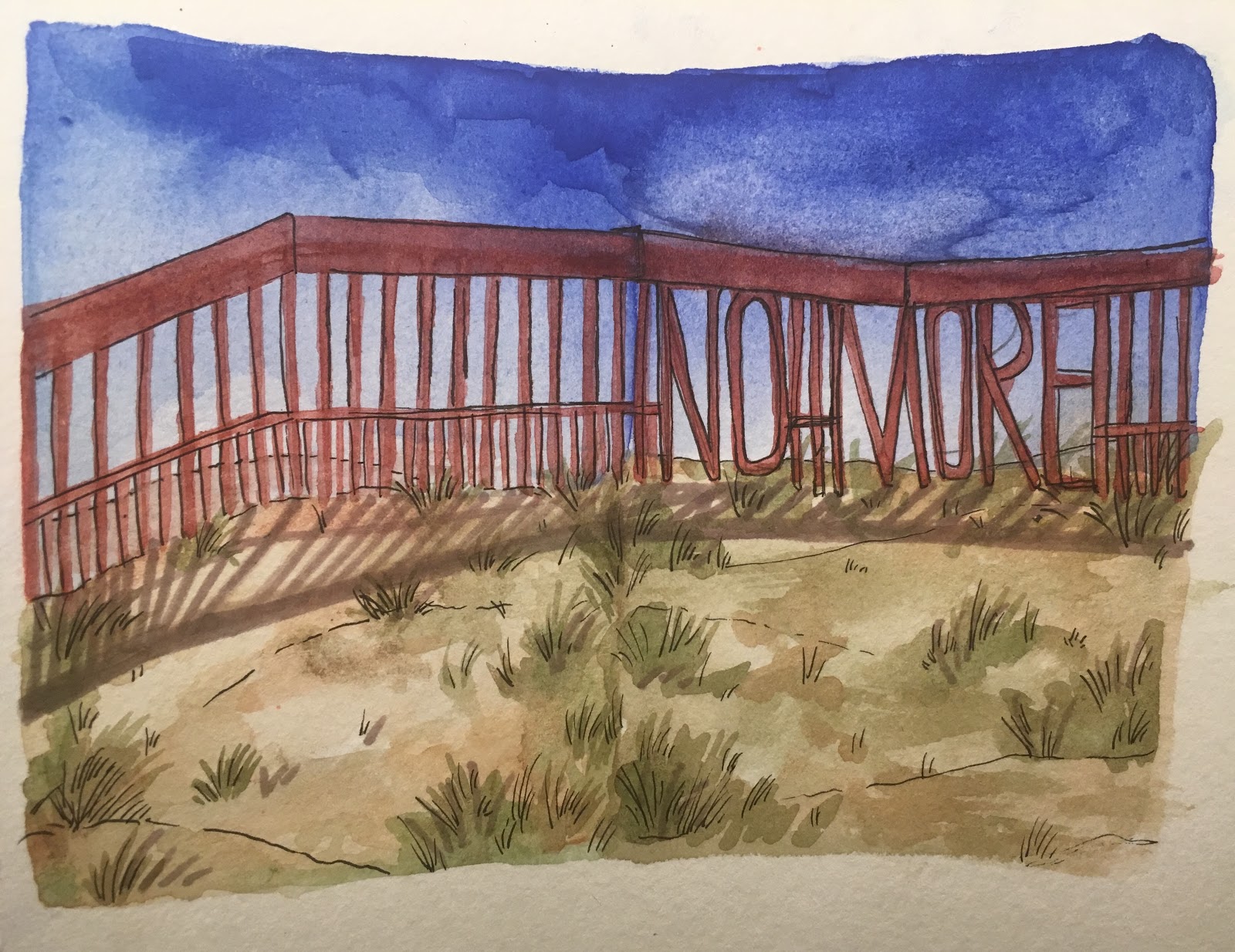

Remnants of the trail are still there despite the “clearcutting” by the timber industry and only those who knew it well will remember the subtle markings and the patterns of the rocks. The spring is still there too, covered by seasons of fallen leaves, sticks and memories of a time forever lost. It is surrounded by a fence, no bigger than a three or four foot square, but clearly designed to keep people away. It is still there, but can no longer be used by the people.

Unfortunately, my story is only one of many that can be told from Native people throughout the country and the PCUSA. We are descendants of those who have survived great tragedy and overcome immeasurable loss yet have managed to embrace and pass down the Christian Faith.

We are descendants of those who have survived great tragedy and overcome immeasurable loss yet have managed to embrace and pass down the Christian Faith.

The Papal Bull, “Inter Caetera,” later to be known as the Doctrine of Discovery has been the source of authority that European Nations and the United States have based their policies regarding their relationships towards the Indegenious people of North America as stated in the following excerpt from The Gilder Lehrmen Institute of American History.

The Bull stated that any land not inhabited by Christians was available to be “discovered,” claimed, and exploited by Christian rulers and declared that “the Catholic faith and the Christian religion be exalted and be everywhere increased and spread, that the health of souls be cared for and that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself.” This “Doctrine of Discovery” became the basis of all European claims in the Americas as well as the foundation for the United States’ western expansion. In the US Supreme Court case Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion in the unanimous decision held “that the principle of discovery gave European nations an absolute right to New World lands.” In essence, American Indians had only a right of occupancy which could be abolished.

We lament the tragedies and losses of our ancestors. And even though the “Church” has actively and passively benefited from these policies, we have embraced the Christian faith as our Tinkba did. Yet we stand ready for a new day — a day in which we use our voices to bring to light the injustice and travesties that have occurred, to insure it does not persist, so that we may build a brighter future for our grandchildren and their grandchildren.

We lament the tragedies and losses of our ancestors. And even though the “Church” has actively and passively benefited from these policies, we have embraced the Christian faith as our Tinkba did

We owe it to our Tinkba to recapture our Indigenous languages and cultural ways and to pass on their teachings, wisdom and faith. We owe it to them to stand against the systematic attack that began over 500 years ago and continues today. We are still here. And now we seek a new direction, built upon the strength of our people. We are knocking on the door of a better tomorrow.

Ron McKinney is a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. He currently serves as the Vice Moderator of Native American Consulting Committee, (NACC), Native American Consulting Council, and Moderator of the Native American Men’s Conference Planning team. He is an at-large member of Dakota Presbytery and employed as a Retention Specialist for TRiO at the Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, KS.

Unbound Social