Editor’s note: As we post this article, the dangers it describes are underlined by the Trump Administration’s efforts to block all international purchases of Iranian oil. A 180-day “waiver” for eight countries to continue importing Iranian oil without punitive action expires on May 2nd. Out of those eight, China, India, Turkey, Japan, and South Korea have not yet ceased importing Iranian oil. It is unclear whether all will agree to do so and how the US will respond, especially if oil prices rise significantly.

God’s reconciliation in Jesus Christ is the ground of the peace, justice, and freedom among nations which all powers of government are called to serve and defend. The church, in its own life, is called to practice the forgiveness of enemies and to commend to the nations as practical politics the search for cooperation and peace. This search requires that the nations pursue fresh and responsible relations across every line of conflict, even at risk to national security, to reduce areas of strife and to broaden international understanding…. Although nations may serve God’s purposes in history, the church which identifies the sovereignty of any one nation or any one way of life with the cause of God denies the Lordship of Christ and betrays its calling.

~The Confession of 1967

With the recent vote by the Methodists against LGBTQ rights and the conversations I’ve had around it, it has been sad to see the church slip another rung down the relevance ladder. “This is why I don’t go to church anymore,” I was told by a friend. So with that story of internal division as the largest mainline church headline so far in 2019, what are we as the church called to do and say about increasing international disorder and hostility? How do we stay engaged and assure we are doing all we can to protect God’s whole creation? What is required of us, as we seek to open doors to the work of the Holy Spirit?

The above excerpt from the Presbyterian Confession of 1967 was written at the height of the Cold War and nuclear arms race; it calls the Church to the search for cooperation and peace, and warns against betraying that calling. By the mid-1980’s, the Methodists, the Roman Catholics, and other churches had joined in supporting the nuclear freeze and other disarmament efforts, arguably decreasing tensions between peoples and helping bring down the “iron curtain” in 1989. Then, with the turn to war after the events of 9/11, the churches—and much of society—paid less attention to nuclear proliferation. The Obama administration’s work to forge a multi-national nuclear treaty with Iran was a welcome change of direction, but it didn’t hold.

___________________________________________

[F]or those with eyes to see, it is hard to miss the hypocrisy of the Trump Administration pulling out of the nuclear agreement with Iran while playing footsie with North Korea.

___________________________________________

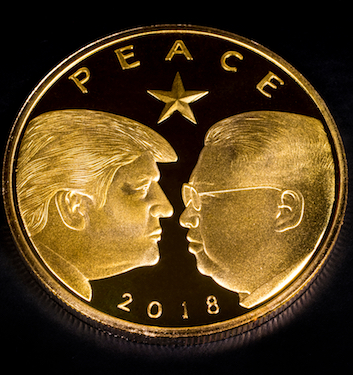

Jesus warned against hypocrisy, and for those with eyes to see, it is hard to miss the hypocrisy of the Trump Administration pulling out of the nuclear agreement with Iran while playing footsie with North Korea. Many proponents of denuclearization of North Korea were worried that Mr. Trump would throw the baby out with the bathwater when he met with Kim Jong Un in Hanoi this year, concerned that he would give away too many concessions for a “deal signing” photo-op. Some have even said Trump’s talks with Kim are all about setting up his Nobel Peace Prize so he can cross that off his Obama legacy list.

It is still unclear what or who pulled Mr. Trump back from the brink of signing a bad deal with North Korea, but one thing is clear. As former National Security Advisor Susan Rice said in the same week, “President Trump has declared himself content with a nuclear armed North Korea. Not only is this a dangerous reversal of decades of American policy, which has long sought the ‘complete, verifiable, irreversible denuclearization’ of the Korean Peninsula, it amounts to acceptance of North Korea as a nuclear state.”

How is this better than the JCPOA signed with Iran in July 2015? Until the signing of that agreement, Iran had been engaged in efforts to acquire the capability which would allow them to develop nuclear weapons. Although Iran always maintained that its efforts were for peaceful purposes, the P5+1 powers did not trust Iran to avoid the leap to weapons. The Arms Control Association notes,

“it remained uncertain whether Tehran would have made the final decision to build nuclear weapons, [since] it had developed a range of technologies, including uranium enrichment, warhead design, and delivery systems, that would give it this option in a relatively short time frame.” [2]

With the added element of Israel’s far-right government threatening military action to stop Iran’s nuclear program, it was always going to be a highly political and difficult process to get all the right parties to the table, let alone reach an agreement. The Herculean task was in fact achieved in the JCPOA (a 150-page document),[1] which took two years of intense negotiations and which the people of Iran celebrated in the streets into the night hours. The “man on the street” there was not interested in having nuclear weapons; all they knew was that sanctions imposed on the banking system had crippled their economy, and that no amount of national pride and no nuclear program was worth being cut off from the rest of the world like a pariah state. The people had truly been suffering, with a currency collapse, shortages of everyday medicines, hyperinflation, unemployed youth, and all that comes with those economic forces. They welcomed and celebrated the agreement, and the returning foreign minister, Javad Zarif, was met at the airport with throngs of people who hailed him as a hero.

The Iran nuclear deal was a compromise agreement, and as with all compromises, it wasn’t perfect for anyone, but everyone walked away with something good: Iran agreed to limit the scope of its research, reduce its stockpile of uranium, and submit to monitoring requirements, while the United States and its allies agreed to drop their nuclear-related sanctions and UN sanctions against Iran. This is the big picture covered by the agreement, which is still holding with all the signatories, except for one. Mr. Trump pulled the US out of the agreement in May 2018, against the wishes of US allies who are still holding Iran to the agreement.

In anticipation of Trump’s trip to Vietnam and the talks to denuclearize North Korea, Susan Rice argued that the Iran deal demonstrated a successful method of negotiation:

“The model for [a good] approach, anathema as it is to Mr. Trump, is the Iran nuclear negotiations. First, the Obama administration reached an interim agreement with Iran to freeze its nuclear development and roll back aspects of its program in exchange for limited and reversible sanctions relief. This Joint Plan of Action created the conditions for extended negotiations to achieve — over a year and a half later — a final, verifiable deal to denuclearize Iran. This plan was affirmed by Congress and enshrined in international law. Iran was fully adhering to its obligations when the Trump administration unilaterally withdrew last year.” [3]

Replicating that proven process would have been the right way to go. Having instead turned our back on that approach, we are now at a dangerous crossroads. Not only has Kim Jong Un’s confidence grown in how much he can now push the boundaries of nuclear testing and development, but there are now also disturbing signs that Iran may be destabilizing. After withdrawing from the JCPOA, the Trump Administration re-imposed severe sanctions on Iran, which—contrary to what politicians say—affect the people more than the government and are indeed traumatic and painful for the average citizen. Because of the renewed sanctions, the benefits of the remaining agreement with the other signatories have not materialized for Iranian society and the people are still suffering from all kinds of shortages in a tenuous economy. This does not bode well for the reformist government of Iran’s President Rouhani or for regional stability.

The last time a reformist government in Iran cooperated with the West was after the attacks of 9/11 when the reformist government of President Khatami helped the Bush Administration in the efforts to defeat the Taliban in Afghanistan. The Iranians are no friend of the Taliban, and they cooperated with American troops in the efforts to oust the Taliban from Afghanistan. It was a risky move for Khatami to help Bush, and the risk did not pay off for him politically. When the US no longer needed Iran’s help, they threw Khatami under the bus; the Iranian electorate then “rewarded” Khatami’s cooperation with the Americans by ousting him from the presidency.

___________________________________________

Efforts at isolation and intimidation, such as the expanded sanctions the US is now seeking on oil purchases from Iran, further undercut the multi-party trust needed for any of the nonproliferation and treaties and steps toward universal denuclearization.

___________________________________________

That mishandling of foreign policy by the US brought about the two four-year terms of the hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad; it can be said that we “made” Ahmadinejad. The same fate could result for the current reformist government that has been taking political risks within the system to reopen Iran to the world. The reformers could easily be ousted and replaced with another era of hardliners if Iranian citizens come to see cooperation with the United States as unwise and misguided.

In this time of perilous choices, the church must fulfill its covenant and calling. As people of God, will we people in the pews do our part? As long as some countries have nuclear weapons and others do not, a foreign policy based on forcing Iran to cease and desist, at the cost of all other consequences, has no moral basis—just as a foreign policy that gives a pass to a ruthless dictator in North Korea, responsible for starving his own people, has no moral basis. The disproportionate fixation on Iran, of course, only reinforces the reluctance of other nuclear powers such as Israel, India, and Pakistan to submit to any objective international agreements that might later be undermined by the US.

As we say in Persian, “az doh haal kharej neest!” or, “there are only two ways out.” We could engage, discuss, seek to understand the other, and find a way through that respects the interests of all. Theologically, it’s called reconciliation, which always begins with confession. Alternatively, we could seek to intimidate and overpower the other side, with whatever instruments of power are at play—military, diplomatic, economic, and more.

Efforts at isolation and intimidation, such as the expanded sanctions the US is now seeking on oil purchases from Iran, further undercut the multi-party trust needed for any of the nonproliferation and treaties and steps toward universal denuclearization. “The onus is on the United States. We never left the negotiating table,” said the Iranian foreign minister this week, adding that Washington should speak with the Iranian nation in the language of “respect.”

Jesus always calls us to take the path of inclusion and reconciliation because it is the way of God. In the end, reconciliation will include a change of hearts; that is the work of God and the Holy Spirit. That work is out of our hands, but our own actions are not. Do we confront and seek to overpower, or talk and seek to reconcile? Do we open our hearts and minds and open the door for the Holy Spirit to do God’s work? Do we, as inspired by our Confession of ’67, “pursue fresh and responsible relations across every line of conflict, even at risk to national security, to reduce areas of strife and to broaden international understanding”? The answer is clear.

God of reconciliation, open our hearts and minds and give us strength for the work of reconciliation.

[1] JCPOA: Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with the P5 +1 – the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council—China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, United States—plus Germany),[a] and the European Union.

[2] https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheet/Timeline-of-Nuclear-Diplomacy-With-Iran

[3] “Can Trump Avoid Caving to Kim in Vietnam?” Susan E. Rice, February 26, 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/26/opinion/trump-kim-vietnam.html

***

Author Bio: Noushin Darya Framke is an Armenian/Iranian Presbyterian elder who has been an American citizen since 1986. She thinks of herself as a product of Presbyterian mission, having attended one of the Presbyterian mission schools in Iran before the 1979 revolution.

Unbound Social