Louis Knowles is Interim Pastor of First Presbyterian Church of Newtown, a multi-cultural congregation in Elmhurst, NY. He has worked on hunger issues, investment in cooperatives in developing nations, and medical care in India, all through ecumenical Christian organizations.

Louis Knowles is Interim Pastor of First Presbyterian Church of Newtown, a multi-cultural congregation in Elmhurst, NY. He has worked on hunger issues, investment in cooperatives in developing nations, and medical care in India, all through ecumenical Christian organizations.

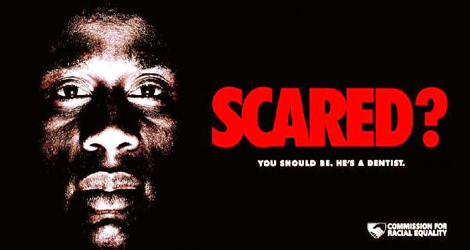

Here in New York City, several hundred young Black and Latino men are stopped and frisked by police officers every day. In 2011 the NYPD stopped and searched more Black young men than live in the city. Every few months an unarmed young Black or Latino man is shot down by city police, sometimes causing an uproar, sometimes not.

Almost fifty years after a confrontation with police sparked the Watts riot in Los Angeles and twenty years after the acquittal of Rodney King’s persecutors triggered another great civil disorder, the police/community interface remains a flashpoint in race relations. Trayvon Martin, a young Black man living in Florida, was killed in a confrontation with a wanna-be cop who was following the national script of suspicion, surveillance, search and sequestration that applies to young Black and Latino men. The wanna-be cop had been sure to equip himself with the authentic badge of U.S. law enforcement: a lethal weapon.

The groundswell of shock and anger that ran through the Black community after the acquittal of Martin’s killer had a strong personal dimension. Thousands of Black and Latino parents who had raised their boys to be proud and independent American men could easily imagine their children falling into the same trap. The fear was almost as strong as the anger.

The groundswell of shock and anger that ran through the Black community after the acquittal of Martin’s killer had a strong personal dimension. Thousands of Black and Latino parents who had raised their boys to be proud and independent American men could easily imagine their children falling into the same trap. The fear was almost as strong as the anger.

The high-running emotions called for a response from church leaders, and executives of the Presbyterian Church in the USA issued a cautious public statement in late July and organized a special Big Tent panel to discuss the case. One can never be sure how a panel of people who do not know each other well is going to work, and this one, despite having good people on it, somehow failed to resonate with the emotional heat that penetrated into even that audience of mostly middle-class, liberal Christians. Only in the last five minutes did it become evident to the panelists themselves that the event had missed its mark; that it had failed to point in a direction that was even remotely appropriate to the depth of the injustice that called it into existence. There was a lot of talk about the great old days of the civil rights movement, the need for a lot more to be done, church efforts to diversify its membership and so forth, but the unfortunate overall impression was of a church leadership that was somewhat vague and insulated when it came to the searing pain engendered by Trayvon Martin’s murder and subsequent events.

We Presbyterians seem to have lost sight of two critical realities:1) The great evil inherent in the color line, which continues to define our society 150 years after the end of slavery and 50 years after the collapse of legal racial segregation. Rooted in the history of enslavement of Africans and the conquest of the native peoples of the Americas, the color line carries this ancient evil into our future, infecting every aspect of our national life. 2) The need for a relentless and focused battle to promote racial justice. Without this battle, without this focus, the color line will persist and may very well deepen. The pursuit of racial justice is different from the pursuit of diversity in our church membership; it is different from the struggle to end poverty; it is different from the effort to include people of all sexual orientations in our communion.

The pursuit of racial justice deserves critical organizational attention and financial and human resources and it deserves a clear and powerful Christian voice. Most of all, the struggle needs passion, the emotional commitment of all those who can imagine the horror of our children losing their lives in a moment of racially-fueled confrontation. It may be that the PCUSA has lost the collective will to acknowledge and confront radical social evil, leaving us with a program of pleasant but insufficient social work.

The pursuit of racial justice deserves critical organizational attention and financial and human resources and it deserves a clear and powerful Christian voice. Most of all, the struggle needs passion, the emotional commitment of all those who can imagine the horror of our children losing their lives in a moment of racially-fueled confrontation. It may be that the PCUSA has lost the collective will to acknowledge and confront radical social evil, leaving us with a program of pleasant but insufficient social work.

For a brief time fifty years ago, the national struggle for racial justice was brought into sharp focus by the convergence of the civil rights movement, a progressive Supreme Court and far-sighted Presidential and Congressional leadership. Since then, U.S. society has lost sight of the unfinished agenda of racial justice in a welter of conflicting causes and campaigns. Now, a powerful and mean-spirited right-wing political movement has emerged, fueled by white anxiety about a world that is slipping out of their control. It would be a bad time for the national church leadership to lose its nerve and back down in the face of racist politics. It’s nice to be a big tent, but at what cost to our national moral life?

Unbound Social