Back in 2005, I wrote an essay entitled “Shame as a Political Virtue.” [1] It began as follows:

I was standing in the checkout line at Blockbuster Video and couldn’t help but notice two young boys running wild near by. One of them ran beside a shelf with toys on it with his arm extended so as to knock them onto the floor. The other had found a small bag with toys or candy or something in it and was using it as a hammer to pound on the shelf from which it had been taken. Unable to restrain himself any longer, a gentleman standing nearby rebuked the boy, informing him not only that the bag was not his, but also that it was not a pounding toy in any case. The mother, who up to this time had been totally oblivious, suddenly became alert. And angry. “You mustn’t scold him,” she said. “He’ll feel bad.”

I found myself thinking, “The cult of self-esteem run amok” (p. 231).

I was reminded of my own very different childhood. When my behavior failed to live up to expectations, I could count on hearing my mother say, “Shame on you!” or “You ought to be ashamed.” Sometimes that was enough. Other times the scolding was a prelude to a punishment. But whether that meant being sent to my room, or standing in the corner, or being spanked, shame was an essential ingredient in the punishment, along with whatever other unpleasantness was involved – and this was intended.

___________________________________________

The 2016 presidential campaign has provided a scary example of political shamelessness.

___________________________________________

I lived in a (familial) culture in which part of what it meant to be a “good boy” was to feel shame when I had been a “bad boy”. I was supposed to experience shame. This corresponds to a major tradition in philosophical ethics, one which takes duty to be the fundamental concept and which has Kant as its paradigm. Put differently, failure to experience shame was to lack a character trait on which the cohesion of the (familial) community depended. This corresponds to the other major tradition in moral philosophy, the one which takes virtue to be the fundamental concept and which has Aristotle as its paradigm.

Both traditions are very much alive and well in contemporary ethical theory. They are not mutually exclusive, but they place the emphasis in different places. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Confucian tradition. It is not only another paradigm of the virtue tradition in ethics; it makes the clearest and strongest case for shame as a political virtue.

Both traditions are very much alive and well in contemporary ethical theory. They are not mutually exclusive, but they place the emphasis in different places. Nowhere is this clearer than in the Confucian tradition. It is not only another paradigm of the virtue tradition in ethics; it makes the clearest and strongest case for shame as a political virtue.

How did I get so quickly from ethics to politics? For both Aristotle and the Confucian tradition, ethics and politics are two sides of the same coin. The virtues are personal excellences, to be sure, but we might call them the virtues of citizenship, for, as suggested above, they are character traits on which the health of the community depends.

Thus, for the Confucian tradition, a shameless society is a sick society, quite literally. The body politic is an organism that, in the absence of shame, is not functioning properly. It is in a state of disintegration and decline. Society requires a certain measure of conformity and cooperation lest it lapse into anarchy, the ongoing (political and cultural) war of all against all. A basic Confucian insight is that a society that that takes duty to be fundamental and relies on law and the fear of punishment alone will foster an unhealthy individualism, a calculating self-interest that weakens the social instinct. By contrast, a culture that teaches its members to feel shame properly appeals to the social instinct, the desire to belong, to be part of something greater than oneself. It is as if “liberty and justice for all” presupposes a deep and effective sense of “We the people.”

___________________________________________

A culture that teaches its members to feel shame properly appeals to the social instinct, the desire to belong, to be part of something greater than oneself. It is as if “liberty and justice for all” presupposes a deep and effective sense of “We the people.”

___________________________________________

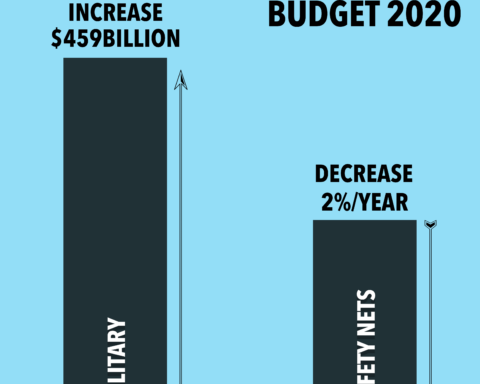

In a polity without shame, officials calculate the best ways to get re-elected by putting together a coalition of (self) interest groups. Who then makes the common good their highest concern? In such a culture, does the notion of a common good even have any meaning? Shame can be helpful here, for in shame I approve of the other’s disapproval of me. [2] This presupposes that at the very least we have some common values that go beyond the freedom of individuals (including corporations, guilds, parties, etc.) to pursue their self-interests.

The individualism of classical western liberalism – the shared foundation of both the left and the right in contemporary politics – will find the communalism of the Confucian tradition a bit stifling. Fair enough. But perhaps it can provide some corrective to an excessive individualism that can find expression, say, in a mother saying, “Don’t scold him. He’ll feel bad.”

The individualism of classical western liberalism – the shared foundation of both the left and the right in contemporary politics – will find the communalism of the Confucian tradition a bit stifling. Fair enough. But perhaps it can provide some corrective to an excessive individualism that can find expression, say, in a mother saying, “Don’t scold him. He’ll feel bad.”

We’ll get precious little help along these lines from discussions of shame in western philosophical traditions. Aristotle is emphatic that it is not a virtue at all, though he makes two concessions that invite a deconstruction of his view. First, shame might be OK for kids. (So why not adults too?) Second, shamelessness is base, even in adults. (So why can’t the right shame be a virtue?) For Spinoza and Nietzsche, shame (along with guilt) is an ingredient in the morality from which they are trying to free us. For Sartre, shame is a decisive defeater of our deepest desire, the desire to be God, the desire of individuals to be their own creator (by the actions they take) and lawgiver (by the norms they choose).

The 2016 presidential campaign has provided a scary example of political shamelessness. Early in the primary season, Donald Trump said, “I don’t have time for political correctness.” Let us first consider what political correctness is in terms of an example. It is now politically incorrect to use the N-word (except among some young African-Americans who use it as a defiant form of self-identification and self-assertion). For most of us (especially those of us who are white), there is a rule against its use, but not a rule of law. It is neither a felony nor a misdemeanor to refer to an African-American in this way. Where this rule is enforced, it is upheld by shame. This is the pattern for political correctness. We have decided (in an informal, cultural way) not to use language that is hurtful to others; and we the people enforce this decision by saying, in effect, “Shame on you!” or “You ought to be ashamed!”

___________________________________________

What is most frightening is not the fact that Hillary Clinton couldn’t have gotten away with even a fraction of Trump’s indecent verbal barrage. What is scary is that so many Americans are drawn to it.

___________________________________________

A summary of Trump’s shamelessness is found in the op-ed piece by Nicholas Kristof in the New York Times entitled “If Hillary Clinton Groped Men.” It consists in a series of “What if Hillary…” questions, followed by ways Trump has kept his promise to avoid political correctness.

Some of these are actions, like his refusal to make his tax returns public or walking into the dressing room of naked women at the Miss USA contest. But most, eighteen by my count, are instances of politically incorrect speech in public (radio or TV). There are repeated crude sexual references, degrading comments about women, and boasts about himself. Kristof doesn’t even mention Trump’s shameless disrespect for military heroes such as Senator McCain or the son of the Gold Star Khan family or his inflammatory comments about Mexicans. He does note that PolitiFact has found 71% of the “facts” they were able to check to be “mostly false” or worse. (I believe ‘worse’ is shorthand for ‘pants on fire.’)

Some of these are actions, like his refusal to make his tax returns public or walking into the dressing room of naked women at the Miss USA contest. But most, eighteen by my count, are instances of politically incorrect speech in public (radio or TV). There are repeated crude sexual references, degrading comments about women, and boasts about himself. Kristof doesn’t even mention Trump’s shameless disrespect for military heroes such as Senator McCain or the son of the Gold Star Khan family or his inflammatory comments about Mexicans. He does note that PolitiFact has found 71% of the “facts” they were able to check to be “mostly false” or worse. (I believe ‘worse’ is shorthand for ‘pants on fire.’)

What is most frightening is not the fact that Hillary Clinton couldn’t have gotten away with even a fraction of this indecent verbal barrage. What is scary is that so many Americans are drawn to it. Interviewing Trump’s supporters, reporters are often told, “He tells it like it is.” They surely can’t be referring to factual accuracy. What they mean, apparently, is something like, “He frees us from the cultural constraints against giving public, verbal expression to our racism (white supremacy), our male chauvinism, our nativism, our religious intolerance. He allows us to be our crude and cruel selves without shame.”

No doubt Trump’s followers are being authentic when they speak as he does (where they think they can get away with it). But when Trump makes a fetish of doing so before national audiences for political gain, a word is needed to distinguish this kind of politics from their (shameful) authenticity. It has recently been coined: authenticism.

In the aftermath of the election, we will soon be like those who have survived a powerful hurricane. The task of cleanup begins. If we are to cleanse our culture from Trump’s authenticism and the authenticity it unleashes, we will need to cultivate a rebirth of shame as a political virtue.

________________________________________________

[1] In Religion and the Liberal Polity, ed. Terence Cuneo (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005), 231-45.

[2] On the basis of this definition, we can see that shame and guilt are not as different from one another as is often suggested, since this definition fits both very well. See God, Guilt, and Death (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1984), pp. 773-78.

AUTHOR BIO: Dr. Merold Westphal is Distinguished Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Fordham University. He is the author of a dozen books and scores of essays. He has served as president of the Hegel Society of America and the Soren Kierkegaard Society and as Executive Co-Director of the Society for Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy (SPEP). He is editor of the Indiana Series in the Philosophy of Religion.

Unbound Social