She, like many others, had asked me about her case. Her rights as a parent were in danger of being terminated, and she wanted to get into a housing program before her approaching hearing. I explained to her that I am not a social worker and offered to connect her to one, but I felt compelled to look into her case as well. Like many others who work in a jail full of people eager to find their way out, I am frequently approached with these requests.

I found out that she would not be cleared to get into any alternative housing program, as there were warrants out for her arrest in other counties. I debated how to (or even whether I should) share this information with her. Later that day, I went to her housing pod to speak with her again and pass on the message. Another woman told me that she had already heard the news and was sobbing in the gym. I went in and found her sitting on the floor, inconsolable, a fellow inmate rubbing her back. My heart went out to them both, and I knelt down in front of her to talk. I told her how sorry I was about this news and that I was also sorry I didn’t have more information. I encouraged her to speak further with her caseworker, but I felt powerless. We prayed together, but that proved difficult as well. I didn’t know the specifics of her background and didn’t know what would be best for her or for her kids. I could only pray for comfort, peace, safety, reconciliation of relationships, and opportunities for healing and change.

I continue to be humbled by how often I am invited into the deepest needs and wrestlings of people who are facing some of the hardest moments of their lives. As strange as it seems, sometimes I find it easier to talk and pray with those who have already suffered tragedy—at least then I know what I’m dealing with. When someone faces potential tragedy (which is often the case for a transitional population), it is much harder. I want to offer hope, but not false hope. In this particular conversation, I was disturbed when a third woman, with the best of intentions, entered our conversation and told the grieving woman to have faith as small as a mustard seed and God will provide. This was not a message I could give in good faith. Yes, God does provide – in amazing and unexpected ways. But how could I tell this woman that God may not provide in the way she wants? No, in moments like this, presence is what was called for. The friend and fellow inmate who sat beside the woman, not saying a word, but offering silent comfort through touch, offered a much better message. That moment will never leave my mind.

Presence is important. The very nature of an incarnational God should speak volumes to us about the importance of presence in a Christian’s call to solidarity. God’s plan for the redemption of creation involved coming down, walking alongside, living amongst, and suffering with his children. God calls us all to share in this work of redemption by loving our neighbors and sharing our lives—not just with those close in proximity or personality, but with all those created by God.

Presence is important. The very nature of an incarnational God should speak volumes to us about the importance of presence in a Christian’s call to solidarity. God’s plan for the redemption of creation involved coming down, walking alongside, living amongst, and suffering with his children. God calls us all to share in this work of redemption by loving our neighbors and sharing our lives—not just with those close in proximity or personality, but with all those created by God.

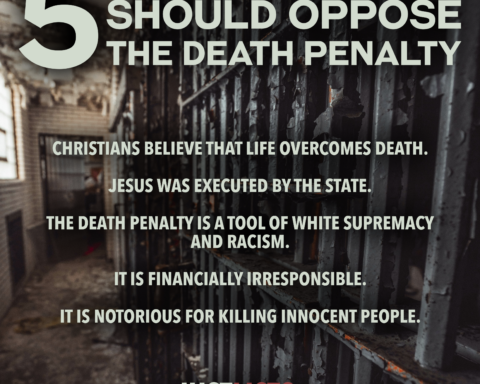

I work with a population who is purposefully kept apart; separated from community by design – as much with stigma as with walls and bars. Even though Christians are called specifically (cf Matthew 25:31-46) to reach out to those who are incarcerated, we rarely do. Instead we judge, believe they are deserving of their separation, or ignore their very existence. I wonder if I ever would have stepped inside a jail myself if it weren’t for the seminary class that first brought me here. Our society is so separated from those caught up in the criminal justice system, and our media and politicians instill fear so deep within us, it is easy for us to stay away. We turn our hearts and minds towards those living in poverty and hunger, but we continue to turn away from those who commit crimes. How different things would be if we heard the message to love offenders as well as victims, realizing that the cycle of crime can be fought though prevention and transformative measures, not merely punitive – providing legitimate alternatives to those caught up in poverty, disillusionment, addiction, and a culture of violence!

___________________________________________

The very nature of an incarnational God should speak volumes to us about the importance of presence in a Christian’s call to solidarity.

___________________________________________

Instead, America incarcerates more of its population than any other nation. The sheer number of those who are or have been caught up in the criminal justice system has created a distinct class of citizen. This class lives caught in a vicious cycle of recidivism, separated from a multitude of rights, and facing incredible obstacles.

Whatever it is that keeps us from answering the call to visit those in prison (fear, anxiety, judgment, separation, distractions of daily life), there is clearly much to be done in the work of solidarity with those who are or have been incarcerated.

As Christians, we are meant to follow a theology of grace, where all are offered mercy and redemption. We are called to love, not to condemn. We are called to listen, and to act. Maybe we are called to speak against the structures that have built up the system of mass incarceration. Maybe we are called to create and work for programs that offer second chances. Maybe we are to work in prevention – fighting violence and crime before it begins. We are definitely called to do something.

As a pastor, program director, and a Christian woman, I am still sorting out my role in this complicated system. There are no simple answers. Seeking solidarity with those who are lost, lonely, and separated is not an easy task and will likely require difficult conversations and much more difficult action. It will require courage and commitment. It will take a lot of prayer and guidance. I don’t know where it will all lead. But I know it begins with being present.

AUTHOR BIO: The Rev. Caitlin Werth is the director of the HOPE Pre-Release Program at Allegheny County Jail, an inter-faith, rehabilitative, re-entry program for men and women who want to restore their relationship with their God, rebuild their lives, and reconcile to their community.. Caitlin enjoys being outdoors, running, reading, and spending time with her family.Read more articles in this series.

Unbound Social