Zero Dark Thirty, Reviewed.

-by Rob Moore

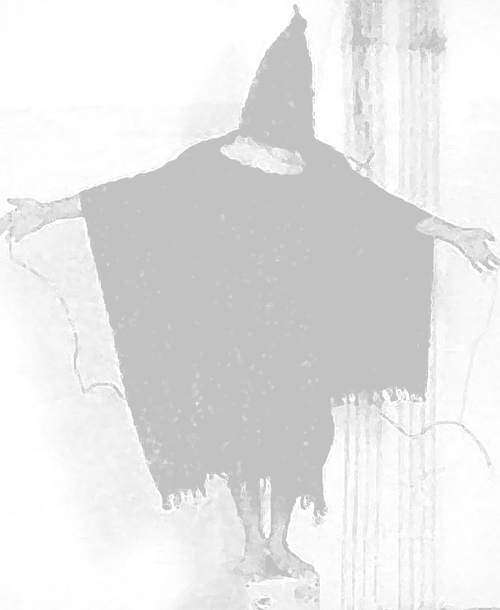

Kathryn Bigelow’s film is the spiritual successor to 2008’s tremendous “war-is-a-drug” Oscar-winner The Hurt Locker, and in many ways is that film’s long, messy conclusion. In The Hurt Locker she explores themes of heroism, recklessness, and adrenaline addiction stemming from long-term combat deployment. In Zero Dark Thirty, we see the shadow side of the war on terror, not fought with guns, but by analysts behind desks, computers, and most controversially, masks. No commentary on Zero Dark Thirty is complete without a statement on torture.

Kathryn Bigelow’s film is the spiritual successor to 2008’s tremendous “war-is-a-drug” Oscar-winner The Hurt Locker, and in many ways is that film’s long, messy conclusion. In The Hurt Locker she explores themes of heroism, recklessness, and adrenaline addiction stemming from long-term combat deployment. In Zero Dark Thirty, we see the shadow side of the war on terror, not fought with guns, but by analysts behind desks, computers, and most controversially, masks. No commentary on Zero Dark Thirty is complete without a statement on torture.

Zero Dark Thirty is not a film about torture. It is a film containing torture – some of the most realistic, nauseating, and riveting scenes of torture ever filmed- but torture is a device, and the movie treats it as such. It avoids, to an almost paranoid degree, moralizing or criticizing the actions depicted on-screen. The film instead opts for showing us, often silently, the weight and consequences of that torture on both the tortured and the torturers. As the film progresses, we see, clearly, the slow erosion that the barbarism of torture takes on its characters; but still it refuses to comment. Bigelow instead opts to give us a document, a device, to view an empirical fact.

America, as a country, through its military-intelligence arm, broke international law and subjected individuals to “enhanced interrogation” with what we now know to be a shocking and brutal regularity. It was done, as we now know, over protests and with encouragement, with great debate and controversy before the American people were ever made aware of it.

Zero Dark Thirty is an important film because it is as close to being directly shown the consequences of our national fixations as we will ever get. People need not be people of faith to agree that such trespasses against basic dignity, regardless of law, are morally significant actions. As the world economic and military mega-power, nothing can be more important for us than to be confronted – directly and visually – with what we have wrought. We may not have held the burlap sack, or the jug of water, or tied the knot on the rope – but we empowered the individuals who did so with our indifference, our ethic of proximity, and our obsession with victory at any cost.

___________________________________________

The film itself is, in many respects, a kind of moral torture. It is torture for moral people to see the consequences of our desire for security.

___________________________________________

There are spoilers for both films in the following paragraph:

The Hurt Locker is a kind of movie-about-movies picture, replete with pointed references to the culture of swaggering masculinity that empowers the incredible competitive prowess of the American culture; but is also about the stark consequences of that same testosterone-fueled addiction. In many ways, Zero Dark Thirty picks up where The Hurt Locker ends – with a soldier telling his infant son there is only one thing in the world he truly loves. The scene changes, and we see he has gone back to the war he is now hopelessly addicted to.

Zero Dark Thirty takes that theme of “victory at any cost,” and shows us that the costs are indeed high – our humanity, our national moral standing, our sense of self – but that we are willing to pay it for one gripping conclusion – victory through death. The final thirty minutes of the film are not “edge of your seat,” they are: “I was sitting? In a theatre?” It is an ironic, slow-paced, and brutal denouement to the largest manhunt in history – three muffled shots, a thump, and revenge is complete. It is isolating, still, and profoundly unsatisfying.

The film itself is, in many respects, a kind of moral torture. It is torture for moral people to see the consequences of our desire for security. It is torture to see what the heroes and brutes, to whom unlimited freedom is effectively given, do with that freedom. It is torture to see the humanity of the tortured, to know that his humanity is altered and ours is diminished through these actions. This is why I found the controversy surrounding torture in the film to miss an essential point.

By not moralizing- The hero suddenly realizes this is wrong and crusades to stop it! or demonizing – What a low and vile group of thugs are the officers who did this! – Bigelow has allowed us to look at a snapshot, not a stylized relief, of the consequences of our national addictions to security, petroleum, and revenge. Had she taken a stand, we would be forever interpreting what was “meant” and “intended” with the actions of the film’s protagonists. But by showing torture – without cutting away, obfuscating, or rationalizing – she has allowed us to experience more fully the moral weight of who we are as a military superpower. We are not led to a conclusion, but asked to come to our own.

By not moralizing- The hero suddenly realizes this is wrong and crusades to stop it! or demonizing – What a low and vile group of thugs are the officers who did this! – Bigelow has allowed us to look at a snapshot, not a stylized relief, of the consequences of our national addictions to security, petroleum, and revenge. Had she taken a stand, we would be forever interpreting what was “meant” and “intended” with the actions of the film’s protagonists. But by showing torture – without cutting away, obfuscating, or rationalizing – she has allowed us to experience more fully the moral weight of who we are as a military superpower. We are not led to a conclusion, but asked to come to our own.

It is Kierkegaard who argues that our own existential responsibility comes in claiming the subjective passions of our humanity, and weighing those passions into a “leap of faith” that would allow us to become authentic and morally realized human beings, whose motives and aspirations more closely resemble the divine. A film like Zero Dark Thirty does not push us toward such leaps, but instead provides us, dispassionately and without commentary, the necessary tools and visual imagery to look within ourselves and know – truly know – what we have wrought. It is a film that demands of the moral thinker a kind of consequentialist reaction, a basic statement of being: Who am I? What do I participate in? And how will I go forward with my life now knowing and seeing these realities?

I’m uncertain what else we could ask of art. What I do know is that this film, ridden with problematic and explosive violence, propels its viewer into moral reflection and an unavoidable spiritual inventory. This is high, necessary, and consequential art of national importance.

|

Zero Dark Thirty Trailer |

-by Rob Moore

Rob Moore is an interim editor of Unbound, a former PCUSA YAV, a film nerd, a gardener, and obsessed with taking photos of flowers.

Unbound Social