Practical Ideas for Taking Action

[wpcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]Economic injustice and the economic crisis can seem so expansive and complex that it is often hard to imagine any kind of action on our part that can make a difference. So let us take a step back and reflect strategically. What can we do?

We can act now with ongoing efforts.

Join the Coalition of Immokalee Workers in demanding fair food from our supermarkets.

Take the Food Stamp Challenge: Devote a week to living on the food budget of food stamps.

We can change our personal consumption practices.

Our personal interactions with the economy can perpetuate or undermine injustice. Examining and converting our lifestyle to one more consonant with justice, sustainability, and the will of God accomplishes two things: first, we get closer to God, we become better people, we get to experience the wholeness and simplicity of a life in covenant with God; secondly, we model for others, including our children and families, an alternative lifestyle, showing them that they have the freedom to choose how they live and that a just and sustainable lifestyle need not be a “sacrifice” – that, in fact, a reduction in consumption and waste can help create a life far more fulfilling and enjoyable than the alternatives, such as by creating more time to talk and be with friends and family.

- Examine your current consumption practices. How much waste do you produce? Where are your clothes manufactured and by what methods? What exactly is “in” the food you eat and where does it come from? How much money do you spend each week and on what?

- Examine the impact of these practices on your own well-being. Are you happy? How much time do you spend shopping versus talking with your family, being outdoors, learning, etc.? Are you healthy in mind, body, and soul? Are there carcinogenics in your food?

- Examine the impact of these practices on others’ well-being. When you take out the trash, where does it ultimately go: a dump, for instance, in a low-income neighborhood that pollutes the air, infects the ground water supply, and defines home for children not by trees or architecture, but by trash? Whose lives went into making that shirt or steak or computer? How were they compensated? What are their living conditions like? Could your money be spent on other things, such as food for a hungry person? Could you learn the name of the person who comes by everyday to take out the trash?

- Identify changes you can make, changes that will enhance the quality of your life and the quality of life of others. For instance, by purchasing fair tree, locally-produced, organic, and/or compostable/reusable/recyclable materials, you might be healthier while also supporting local business, better production practices, and workers. Or consider refusing to shop at stores that exploit laborers in other countries, or forbid unionizing, or demonstrate racist and sexist practices in hiring and promotion.

- Create a step-by-step plan, such that you enact a change each week. Consider gathering friends, congregation members, family members, or colleagues to join you, so that together you can hold each other accountable, perhaps even gathering for meals once a month to discuss the impact of these changes on your lives. This would be a great project for a congregation.

- Do it!

We can be informed and active citizens.

Despite the accrued political power of lobbyists and corporations, our voting choices, participation in political campaigns, and awareness of issues and the truth behind political slogans hold power, individually and particularly collectively.

- Do your homework. Fear-mongering, slogans, and half-truths or blatant lies pervade the public arena. Find out what is really behind an issue or politician before making your decision.

- Vote. Elect officials that are informed and willing to act upon economic injustice and inequality.

- Hold your elected officials accountable. If an official succeeds or fails in living up to a campaign promise, let your vote, Facebook posts, letters to the editor, tweets, and conversations reflect that success or failure.

- Recognize that elected officials are representatives of the people, but are not the people. A courageous but alone politician can make little impact. A courageous politician with citizens at his side can change this country. Talk with your elected officials and their staff, visit their websites, and discover how you can work with them.

- Lobby. Organize a group of citizens, formulate your research and proposal(s), identify your credentials (i.e. what power you hold and what communities of voters you represent), and arrange a visit with your elected officials.

We can organize our congregations.

Congregations are great for organizing. They consist of people from across a community who come together weekly or more often around a common set of values. They have relationships with one another and, if a healthy congregation, trust. They have a diverse set of gifts, experiences, professions, and leadership capabilities.

[/wpcol_1half] [wpcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

- Alter the congregation’s practices that infringe on economic justice – where do you buy those plastic cups? What is the pay gap between the pastor and the custodian?

- What are the disparities between your congregation and the immediately surrounding community? Do most of your parishioners come from the suburbs while the church is surrounded by urban poverty? What can you do to become more involved with the surrounding community?

- A congregation-wide commitment to a consumption and impact-reduction stewardship campaign (see #5 under personal consumption practices).

- A Bible study examining economic justice and law from the perspective of scripture.

- An adult or youth education class that explores the history of the church in terms of economic justice. For instance, if you are Catholic, what do your parishioners know about the Catholic Workers Movement?

- Orient liturgy, preaching, prayer, and other aspects of worship to God’s economic justice.

- Incorporate themes of economic justice in Sunday school classes, youth mission projects, Confirmation, and education of prospective and current members.

- The beginning of organizing. Gather a small number of committed leaders in the congregation: clergy, elders, deacons, parents, youth group leaders, etc. Devise a plan to assess the needs, values, interests, and gifts of your congregation, while building (or reinforcing) trust-based relationships. Train and practice doing one-to-one conversations. Formulate a timeline.

- Conduct one-to-ones. Have each member of your leadership team meet with a certain number of parishioners. In those meetings, get to know the parishioner: what is she passionate about? Is he angry? Anxious? Happy? About what? What does she care about most? What is he good at? What does she perceive to be the greatest economic needs of the church and surrounding community?

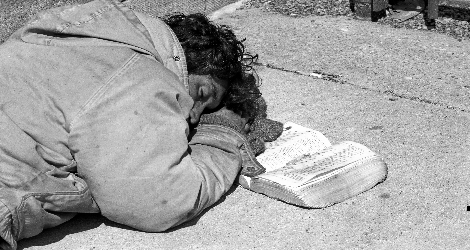

- Consult each other. After the one-to-ones are complete (and perhaps during their execution), reassemble the leadership team. Discuss what you learned. Look for patterns. Are people consistently angry about something? Do details consistently pop up, such as the homeless man sitting outside the church, or being concerned for their children’s economic future? What gifts are present among the parishioners? Who might be good additions to your leadership team?

- Focus. Identify, from your research, one issue. Just one. More can come later. But if you try to do too much from the very beginning, you will end up with what most congregations have: a smattering of different groups with a few devoted members, unable to grow, unconnected with other groups, and ultimately ineffective and frustrating to members. So, choose a single issue that grows out of the deepest concerns, values, and ideas of the parishioners with whom you have talked. What you come up with may be broad: the economic future of young people. But that is a topic, not an issue. Select a specific issue within that topic. For instance: the creation of a community center that trains and educates young people, offers opportunities for mentoring, helps youth identify gifts and talents, prepares them for interviews and resume-writing, employs staff (so job-creating), cultivates fiscal responsibility, and advocates for the employment of its youth members.

- Research. Meet with political leaders, local businesses, banks, teachers, social workers, and anyone else who might have a stake in the issue. Find out all the angles. Who will support such a proposal? Who will oppose? Why? Are there issues and details you had not considered? Such as: Will the community center only create more highly trained and educated young people who cannot find jobs? What will the project cost? Where will the money come from?

- Make your proposal. Based on your research, formulate a specific proposal including the how, the when, the why, and the what. Just as you devised an issue that appealed to a very basic interest and value on the part of your parishioners (concern for their children), find ways to appeal to the basic interests and values of needed allies (businesses, other congregations, political representatives, etc.).

- Take action. Organize an action in front of the courthouse steps, including members of your congregation and allies, as you call for the desired policy/action. Invite the targeted person “in power” to come to your church and answer questions: be sure to mobilize enough people to demonstrate your “power.” Work with leaders in the community to see how you can make this a reality.

We can organize our communities.

Communities (be they neighborhoods, college campuses, schools, retirement and assisted care living environments, or workplaces) can be organized along the same lines as enumerated above for congregations. The same projects and practices can be employed, just perhaps applied to a larger and more diverse collection of people.

Back to Table of Contents

[/wpcol_1half_end]

Unbound Social