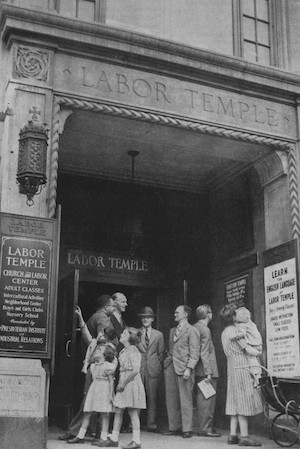

Photo by Ilana Urman

Voting is not just “civic duty.” It is a moral choice.

I still hear the phrase “civic duty” associated with the act of voting…but less and less often. People are tired of political action, and would rather abdicate any and all responsibility for the status quo. To quote my political scientist dad: “Apathy is the most powerful force in American politics.”

It’s easy to sympathize with folks who want no part in politics: it’s not glamorous, it’s not pure. The rhetoric of candidates is often rife with deception. Politics gives its actors an incentive to play on our fears, manipulate our blind spots, and subvert our values.

But when there is a cancer in the body politic, ignoring it will not make it go away. And washing our hands of political dirt does not make us moral actors any more than it absolved Pontius Pilate of his cowardly judgment in Jesus’ trial. We, like Pilate, are called to actively do justice in our society. Will we answer the call any better than he?

___________________________________________

When there is a cancer in the body politic, ignoring it will not make it go away.

___________________________________________

Jesus’ conception of his moral calling had little to do with avoiding “impurity” as understood by his contemporary Jewish society—he walked with lepers, ate with tax collectors, and cared more about what came out of his mouth than what went in. One exception is Jesus’ baptism (connected to Jewish rituals of purification). Primarily, though, Jesus focused on the needs of the marginalized, on community…on justice. And to those ends, he demonstrated a deliberate awareness of the stakes of his actions for other people.

When Jesus tells the story of the “Good Samaritan”—a culturally foreign stranger stopping on the road to help a victimized neighbor in need of medical attention—the point wasn’t specific to trouble on the road, or to hospital bills, or to Samaritans and Jews. The story demonstrates a commitment to a widely-drawn circle of community. And Jesus also gives us examples of people who, in their convictions about personal purity, fail to get the point: the priest and the Levite. Preoccupied by their own routines and self-righteousness, they walk right by the people suffering. They fail to take responsibility for the state of the world.

We make this choice all the time, ignoring the consequences of our choices by pretending that they are non-choices:

It’s only a small fraction of the time that I will stop to buy someone on the street a sandwich.

But that’s normal, isn’t it? We can’t end world hunger with our personal pocketbooks, can we?

We collectively pollute and destroy—not just through greenhouse gases, but also with plastics and styrofoam and coal dust and overfishing—raising asthma levels, once eroding the ozone layer, and destroying our own sustainable food supplies. These are far more tangible consequences than the beyond-comprehension scope of global climate change.

But my own small actions of consumption are tiny compared to the pollution of corporate production, the meat industry, and millions of cars on the road.

The history-defining choices of waging war, destroying cities with nuclear weapons, determining access to education and healthcare, are made by a very few people elected by a minority of the population.

But those are their sinful choices, not mine—I didn’t even vote for them!

Women—and some men—are made to suffer from PTSD, anxiety, and self-blame for decades of their lives after being sexually harassed, assaulted, or raped.

But I’m not a rapist—and how am I supposed to adjudicate truth when it is she-said/he-said?

The economist in me is vulnerable to these cynical perspectives: challenges of collective action are profoundly difficult to solve, whether the suffering induced is personal in scope or global. But humans are more complicated than their incentives and desires—and human society is shaped as much by cultural norms and history as by logic and self-interest.

___________________________________________

There are no shortcuts: building relationship, committing to the common good, and changing the cultural status quo takes a massive effort from people.

___________________________________________

Moral action takes many steps. The act of casting your vote will not magically cure partisan division and bring about a new era of peace and prosperity. Nor will tweeting #IBelieveWomen bring an end to sexual violence and the abuse of power. There are no shortcuts: building relationship, committing to the common good, and changing the cultural status quo takes a massive effort from people. And those people all need to be able to take on responsibility outside the boundaries of self-interest and laziness.

Moral action takes many steps. The act of casting your vote will not magically cure partisan division and bring about a new era of peace and prosperity. Nor will tweeting #IBelieveWomen bring an end to sexual violence and the abuse of power. There are no shortcuts: building relationship, committing to the common good, and changing the cultural status quo takes a massive effort from people. And those people all need to be able to take on responsibility outside the boundaries of self-interest and laziness.

The brilliant thing about Jesus, talking and walking about as a human being, is that he is a tangible demonstration of how to bring about change. He talks about where society is failing. He seeks out uncomfortable places and conversations. He takes on a heck of a lot of responsibility. He puts himself on the line.

___________________________________________

Followers of Christ are called to be engaged in politics, not because they can force society to become ideologically “pure,” but because their own actions matter in pointing toward justice.

___________________________________________

Voting is an important moral act precisely because it involves taking an initial measure of responsibility for the common good. Is it enough in and of itself? No. Does it absolve us of the responsibility to discuss hard questions, and challenge our assumptions, and self-improve? No. But if we fail to contribute to the norms and choices our country is making at the national level by slipping a paper into the ballot box, how much harder will it be to look inward and make the changes in ourselves?

Voting is not just a civic duty. It is a moral choice—a choice to be involved in movements greater than ourselves. Followers of Christ are called to be engaged in politics, not because they can force society to become ideologically “pure,” but because their own actions matter in pointing toward justice. That takes nuance, an open-minded commitment to truth, and an acceptance of responsibility.

___________________________________________

As I watched the proceedings and plans of the Senate prioritize expedience over truth-seeking…I knew the outcome would not be decided by objective truth.

___________________________________________

I wrote the majority of this piece before the testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. But as I listened to her invoke “civic duty” as a reason for her coming forward, as I watched the proceedings and plans of the Senate prioritize expedience over truth-seeking, and as I watched Brett Kavanaugh deny charges while failing to call for an independent investigation, I knew the outcome would not be decided by objective truth. I heard the words of my father ring in my head again: Apathy is the most powerful force in American politics.

I pray that it may not be so. Apathy increasingly becomes another word for complicity.

***

Author Bio: Henry Koenig Stone serves in Louisville, KY as current Managing Editor of Unbound and Associate for Young Adult Social Witness. Originally from Rochester, NY, Henry comes from a long line of pastors and professors. His family has practiced an equally long critical tradition of having “roast preacher” for Sunday lunch. Henry holds a B.A. in Economics (2015) from the University of Chicago and an MPP (2017) from UChicago’s Harris School of Public Policy. His past work has focused on policy analyses of healthcare pilot programs and public health systems. A baritone, Henry is a fan of both sacred and irreverent vocal traditions. His favorite place on earth is Dunkirk Camp & Conference Center, where he has been a summer camp counselor for many years.

Read more from this issue, Make America Just. Period. (A Moral Platform for the Christian “Justice Voter”).

Unbound Social