The Broadway musical Leap of Faith tells the story of Jonas Nightingale, a con man who holds fraudulent, revival-style church services around the country and capitalizes off of people’s religious fervor and subsequent financial generosity. It’s all a stage show – nothing more, nothing less. Actors are paid to cast down their canes and start dancing, to rise from their wheelchairs and feign tearful relief, all with the aim of making a few bucks. But then Jake McGowan, a young, recently disabled person, believes so fiercely in the possibility that God (vis-a-vis Jonas) might restore his ability to walk that he starts to actually recover, forcing Jonas to reconsider his own cynicism. In the end, Jake makes a remarkable recovery, Jonas ends up finding himself moved by the very same faith he used to manipulate others, and the entire cast sings about the importance of taking a “leap of faith” towards the potential for miracles. It’s a brilliant performance that now leaves a sour taste in my mouth. Leap of Faith may be a work of fiction, but it nevertheless points to an important fact:

We need to talk more about how the Church talks about disability.

To be clear, I’m not claiming that all healing services are fraudulent, by any means, nor do I wish to pretend that healing isn’t a central aspect of many faiths, especially Christianity. Truth be told, even while being part of the cast of Leap of Faith (a local, off-Broadway performance, that is), it was easy to get caught up in the moment despite knowing that it was – quite literally – all an act. That said, while the idea of being healed is certainly appealing to many, those of us who expect to live our entire lives with a disability or chronic illness don’t necessarily share that same ideal. As more and more disabled folks speak up about their lived experiences (rather than being spoken for), it becomes increasingly clear that many of us aren’t looking to be magically “healed” from our conditions, but rather met with acceptance, accommodations, and accessibility, things which communities of faith are often less prepared to address.

This shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise; disabilities and chronic illnesses have been (and still are) understood as emblematic of moral failings for millennia. Zechariah is rendered mute for doubting Gabriel’s message (Luke 1). Paul is blinded for his persecution of those who chose to follow Jesus (Acts 9). And people in my life have blamed my own disability on everything from starting hormone replacement therapy (I’ve gone on and off HRT a few times, yet still I’m disabled) to getting vaccinated against COVID-19 (y’know, the mass disabling event), from not eating enough fruits and vegetables (my symptoms started to present while I was on the same plant-based diet I’d been on since I was a teenager, and they’ve persisted despite making various dietary changes) to not lifting enough weights (which I’ve been advised against due to my hypermobility) or doing enough cardio (running cross country is how I found out that I needed the first of my hip surgeries). Even here, in my writings, I feel obligated to demonstrate that my disability isn’t a failure on my part, prematurely defending myself against potential accusations that I am the reason that my body is “wrong.”

And this doesn’t even touch on issues related to mental health or neurodivergence. Autism, ADHD, CPTSD, anxiety, depression – my theology and my identity as a person of faith are naturally impacted by the way my brain works, but I’ve yet to see communities of faith acknowledge the impact of religious dogma and doctrine on those of us whose mental landscape diverges from the “default settings” that undergird so much of our collective experience. And so anxiety becomes a demon to be exorcized. Suicidality is viewed as a sign of a spiritual weakness. Religious trauma is reduced to variations of “people hurt you, not God” or “it’s not our fault you were traumatized by *insert problematic theology here* (hell, the rapture, racism, misogyny, queerphobia, etc.). And those of us who ask too many questions (not uncommonly a result of neurodivergence) often find ourselves at odds with the Church; we risk rejection by the very same people who, at least in my experience, sold both the poison (you’re fundamentally broken and evil) and the cure (aren’t you so glad that Jesus loves you enough to fix you?).

Yet many of us don’t see ourselves as broken humans in need of fixing (at least not because of our neurodivergence or disability), but rather as people living in a world that simply was not made with us in mind. If I can’t bring my walker into a bathroom, the issue is not the fact that I use a rollator for balance and mobility, but the fact that the bathroom was created without consideration for physically disabled people. My partner and I, who have a height difference of 15 inches, both have had issues with cars designed for average height folks because I’m tall and they’re short – which isn’t to say that car design is necessarily a disability issue (though it certainly can be), but it is most definitely an accessibility issue! And it isn’t hard to imagine that if autism were the norm instead of the exception, allistic folks would likely probably have just as much difficulty as autistic people do now in various social situations (eye contact or lack thereof, special interests or lack thereof, direct vs. indirect language, literal vs. non-literal thinking, and so on).

It’s not that disabled people don’t struggle as a direct result of their disability, and not all of those struggles are societal. We may be capable of redesigning our infrastructure, but no amount of reform, no matter how bold or ambitious, is going to suddenly alleviate my chronic pain or allow me to be seizure-free long enough to drive safely again. I desperately wish that I could dance again without worrying about collapsing, and as much as I used to complain about having to walk my dog, the thought sounds absolutely wonderful these days. But having a salient identity that comes with unique struggles doesn’t equate to wanting to risk oneself of that identity. Sure, I want to help create a world that is less racist, misogynistic, homophobic, transphobic, ableist – a world where fewer and fewer people are demonized, dehumanized, and discriminated against based on things that are out of their control – but that doesn’t mean I don’t want to be Black, femme, queer, trans, disabled, or any other identity that currently subjects me to the aforementioned demonization, dehumanization, and discrimination. I stand on the shoulders of a diverse community of giants – Marsha P. Johnson and Judy Heumann, Linn Tonstad and Nancy Eiesland, those who shut down my home state of North Carolina to protest HB2 and those who dragged themselves up the stairs to demand passage of the ADA – and I refuse to abdicate my responsibility to continue the revolutionary struggles of those who have come before me by distancing myself from the very communities that have helped to secure the rights and privileges that I currently have.

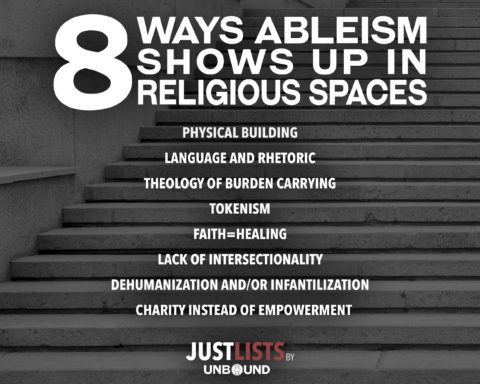

Not only are the rights of all oppressed peoples intertwined, but the claim that all human beings are created in the image of God must include those who exist outside the domain of the expressions of humanity that we deem comfortable and acceptable. If we cannot conceptualize the Divine, whatever that may look like for us, as being representative of the diversity of humanity – white, Black, Latine, Asian, Arab, Polynesian, Indigenous, masculine, feminine, androgynous, straight, queer, cis, trans, nonbinary, rich, poor, young, old, neurotypical, neurodivergent, abled, disabled – we miss the opportunity to witness the ways in which the Divine operates in the context of those who we might otherwise overlook. When Jesus declared that “the least of these” were so close to his own heart that he considered them to be his representatives here on earth – “what you do for the least of these, you do for me” (Matthew 25) – there was at no point an invitation to decide who to exclude from the injunction. And when our collective understanding of disabled folks hinges on the desire to “heal” people of something that is a source of identity and community for so many of us – especially in light of the unique struggles we face in healthcare systems that, once again, were not built with disabled people in mind – the end result is often an attempt to speak for us instead of handing us the microphone.

Of course, there are plenty of disabled folks who do long for healing; Jake McGowan certainly did, at least. I can only speak for my own experiences, and I wholeheartedly reject any and all attempts to tokenize me or my perspectives. If I am the only disabled voice you’ve listened to in a while, consider why that may be and how you might address it; these days, more and more people are speaking out about their experiences as disabled people, especially as social media continues to create space for perspectives that were previously silenced or inaccessible. But in response to the increased proliferation of disabled voices, we must continue to ensure that our voices are not only heard, but listened to – in the public square (whether physical, virtual, or otherwise), in every branch of government at every level (local, state, federal, international), in our houses of worship (across all faiths and traditions), and anywhere where decisions would otherwise be made for us without our input. Because by clinging to the narratives that others have crafted about us and making decisions for disabled people based on these assumptions, we not only end up overlooking things that would actually lead to increased acceptance, more practical accommodations, and improved accessibility, but we also undermine and neglect the myriad gifts that disabled people have to offer within communities of faith – assuming the doors are wide enough for us to enter.

Madelyn Jones, MDiv (she/they) is an educator, poet, theologian, and storyteller whose research interests include queer exegesis, neurodivergent theology, and the intersections of religion and pop culture. A self-described “heretic,” she is especially fond of engaging with the Christian texts that shaped her formative years in ways that push back against traditional interpretations and prompt tough questions that have historically been met with silence and suppression. She is currently in the editing phase for A Heretic’s Lament at the End of the World: Poetic Theologies for Those Left Behind, a collection of poetry dedicated to those whose pursuits of authenticity and the genuine may have distanced them from their faith communities, yet led them closer to the Divine than ever before. When she’s not writing, Maddie enjoys musical theatre (performing and watching), social media (consuming and creating), and video games (playing and designing). A product and current resident of the North Carolina Piedmont, Maddie is quite fond of Cook Out, Cheerwine, and the Carolina Panthers, even if they keep trading all of her favorite players. They are happily married to their partner of nearly five years, and together, they’re raising a “menagerie” of two rabbits, a corn snake, a ball python, and a pitbull mix.

Unbound Social