White Supremacy and the Church

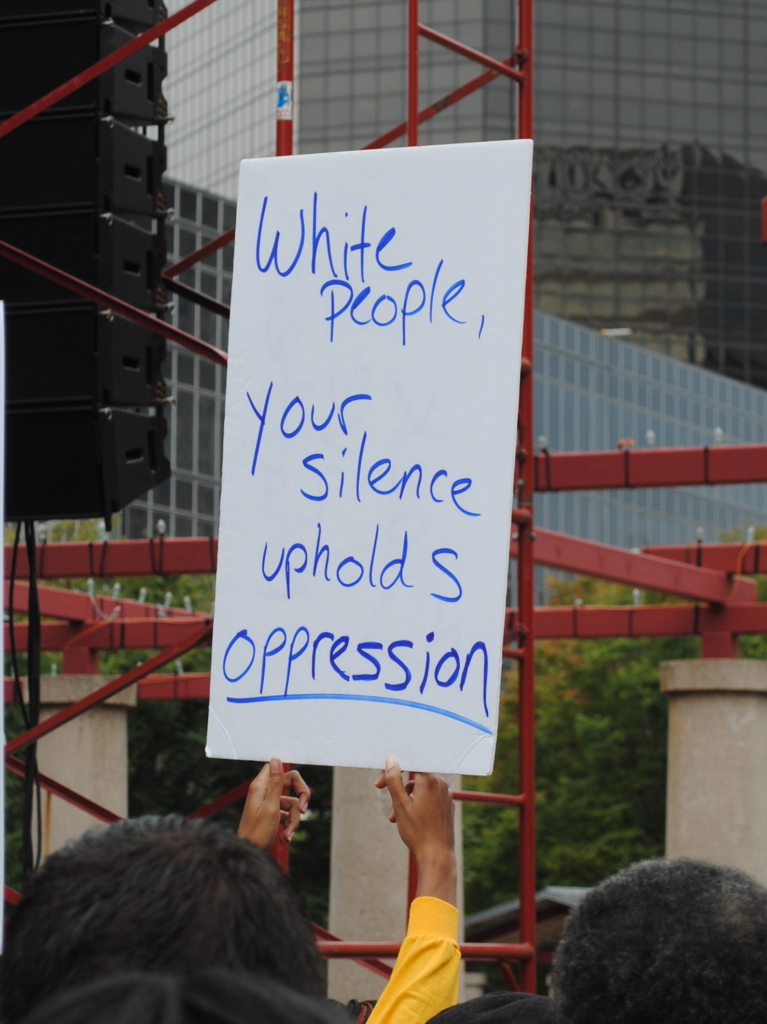

Last week, I once again found myself protesting in the streets of Chicago. Showing up to a demonstration organized by activists of color, I joined them chanting: “White Supremacy is the enemy. Shut it down! Shut it down!”

As I pronounced every word, I felt a liberating sense of relief. “White Supremacy is the enemy. Shut it down! Shut it down!”

The words echoed loudly along the street as they filled the air with the refreshing smell of truth. “White Supremacy is the enemy. Shut it down! Shut it down!”

I felt the empowerment of the moment. The waves of rhythm that kept the chant going began to fill the empty space in my consciousness where those words should have resonated a long time ago. “White Supremacy is the enemy. Shut it down! Shut it down!”

Such a courageous articulation was new to my ears, but it’s not new to my heart. And to be completely honest, realizing this made me really angry. Years of social justice work and community organizing in church settings has never allowed to be to be present to that reality. No liturgical resource, no confession of sins, no proclamation of the Word has allowed me to name it. “White Supremacy is the enemy. Shut it down! Shut it down!”

___________________________________________

For years, I have fallen in line and left my anger at the door of the sanctuary. I refuse to continue to do so.

___________________________________________

My tragic realization that day was this: I’ve been taught that there’s no place for rage in the church. That my fury against the sin of white supremacy, racism, and racial injustice can only belong to the streets.

Let me be clear: I am angry at the reality of racial violence. I’ve been angry for a long time now. For years, I have fallen in line and left my anger at the door of the sanctuary. I refuse to continue to do so. I refuse to dismiss and disguise my anger for the sake of keeping everyone at church comfortable.

As a community organizer and now as a seminarian, I have asked myself repeatedly: Shouldn’t we all be angry? If you were standing at the foot of the cross, wouldn’t you be angry? Could you look at our beloved Jesus – advocate of the poor, crucified by the Empire – watch his blood drip from wounds of hatred, and not feel anger?

As a community organizer and now as a seminarian, I have asked myself repeatedly: Shouldn’t we all be angry? If you were standing at the foot of the cross, wouldn’t you be angry? Could you look at our beloved Jesus – advocate of the poor, crucified by the Empire – watch his blood drip from wounds of hatred, and not feel anger?

Without going through the anger and rage of Good Friday, how can we expect to make it to joyful news of Easter Sunday?

All around us, Jesus is being crucified again and again. I witness the crucifixion every time a black man is shot by a police officer, every time a family is separated by deportation, every time a woman experiences domestic violence or rape is used as a weapon of war, every time another person of color is sent to jail. When exploitation and injustice are infused into our daily lives, crucifixion is a living reality. The powers of white supremacy and racism, upheld by the complicity, apathy, and silence of those who refuse to act, continue to crucify our brothers and sisters of color. What’s worse, this crucifixion is happening under the watch of the Church.

___________________________________________

In a Church and a society whose awakenings to justice have taken too long, to be angry is to participate in the subversive endeavor of feeling.

___________________________________________

For that reason, I will no longer leave my anger at the door. Today, I embrace my anger as a natural reaction to the destructive force of white supremacy. As activist and scholar Audre Lorde has famously said, “Anger is an appropriate reaction to racist attitudes, as is fury when the actions arising from those attitudes don’t change.”

My anger is an embodied resistance to white supremacy and the ways it continues to kill our communities. My anger is a manifesto of indignation, an exclamation of rejection not only of the racism that I have experienced as a Latinx, but also the racism in which I myself have been complicit. My anger is an attempt at authenticity.

In a Church and a society whose awakenings to justice have taken too long, to be angry is to participate in the subversive endeavor of feeling. I am angry because I have been in the presence those who have suffered the devastation of white supremacy and racism, and I have loved them deeply.

In a Church and a society whose awakenings to justice have taken too long, to be angry is to participate in the subversive endeavor of feeling. I am angry because I have been in the presence those who have suffered the devastation of white supremacy and racism, and I have loved them deeply.

Last month, while participating in a church gathering for Presbyterian seminarians, I participated in an activity in which we were asked to choose an image to represent the church and what it means for the world. I looked down at the colorful collage of options before me. What was the church for the world? I considered the forests, portraits of people vacationing in other countries, flowers, buildings, and puppies.

And then I found the tornado. The next thing I knew, I was articulating the ways in which this brutal force of nature genuinely evoked how I see the church working in the world. What was supposed to be a hopeful exercise during a nice gathering quickly evolved in my usual list of grievances. But for me, the image of a tornado breathes life into the reality of an institution that has been complicit to white supremacy, colonialism, racism, and so many more forms of oppression. There I was, the angry women of color in the room. It’s an exhausting and incredibly lonely place to keep finding myself.

___________________________________________

My anger is an embodied resistance to white supremacy and the ways it continues to kill our communities. My anger is a manifesto of indignation, an exclamation of rejection not only of the racism that I have experienced as a Latinx, but also the racism in which I myself have been complicit. My anger is an attempt at authenticity.

___________________________________________

In my experience, the Church has demonized anger as problematic, unruly, and troublesome. Consequently, it took me many years to even begin to pursue reconciliation with my own feelings of indignation in the face of injustice. But since then, I have grown to understand my anger as an engine for change. It has been the fire that moves me to action: to organize, to protest, to advocate against injustice. Anger, complemented by the transformational power of love, has kept me fighting for justice while remaining hopeful for the possibility of liberation. My participation in that holy struggle has kept me pursuing and re-imagining ministry.

I want to serve a Church that is authentic and relevant. I want to be embraced by a Church that understands my anger and is willing to hold the tension it brings. Beyond acknowledging the reasons in the world to be angry, I want to serve a Church that will dare to feel that anger. I want to serve a Church that is present to suffering and crucifixion.

We live in a world that has normalized brutalization, racism, and violence. In such a world, the Church is called to be uncomfortable, to embrace the unease of truth and use it to challenge structures of power. Approaching the unease of truth starts with engaging in relationship with those who are surviving the devastation of racism. We need to let the suffering of a legacy of pain give its testimony. Our job, as the Church, is to listen. And I truly believe that once we have listened and felt the pain, we will see that it is impossible not to be angry. Only then can love reveal its redemptive power.

We live in a world that has normalized brutalization, racism, and violence. In such a world, the Church is called to be uncomfortable, to embrace the unease of truth and use it to challenge structures of power. Approaching the unease of truth starts with engaging in relationship with those who are surviving the devastation of racism. We need to let the suffering of a legacy of pain give its testimony. Our job, as the Church, is to listen. And I truly believe that once we have listened and felt the pain, we will see that it is impossible not to be angry. Only then can love reveal its redemptive power.

Until then, I will continue to find healing chanting in the streets rather than in seminarian gatherings. And I will look forward with hope to that day that Church embrace me whole, with all my anger and my love. Only on that day, will I be able to claim the Church as a space that is truly mine.

*****

AUTHOR BIO: Stephanie Quintana-Martinez is a first year Masters in Divinity student at McCormick Theological Seminary. Before moving to Chicago, Stephanie worked as a community organizer at Southside Worker Center and the Tucson Protection Network Coalition working on issues of immigration justice in Arizona. Stephanie is an ordained ruling Eeder in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and is currently under care of Southside Presbyterian Church on her path to ordination.

Read more articles in this issue Call to Confession: Race, White Privilege and the Church!

Unbound Social