View and print as PDF

View and print as PDF

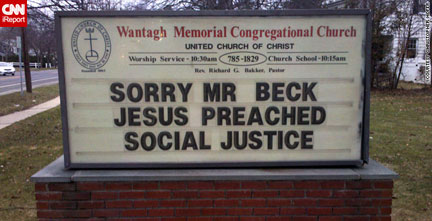

About a year ago, then T.V. and radio celebrity, Glenn Beck, told the world that there is no place in Christianity for social justice. The terms “social justice” and “economic justice” were, he said, mere code words, representing the infiltration of political agendas incompatible with Christianity.

About a year ago, then T.V. and radio celebrity, Glenn Beck, told the world that there is no place in Christianity for social justice. The terms “social justice” and “economic justice” were, he said, mere code words, representing the infiltration of political agendas incompatible with Christianity.

Christians were quick to respond. They pointed to scripture, to Exodus and the prophets, to Jesus’ beatitudes and statements on the poor, to the early church in the Book of Acts. They lifted up a long history of Christian resistance to oppression and exploitation. They spoke of Bonhoeffer and Karl Barth, and their resistance to Nazism—resistance which resulted in Bonhoeffer’s execution. They asked, “What about Martin Luther King Jr., Desmond Tutu, Mother Teresa… heck, what about Jesus?” Notable Christian leaders, such as Rev. Jim Wallis (evangelical and president of Sojourners) and the Rev. Peg Chemberlin (president of the 45 million member National Council of Churches of Christ U.S.A.), spoke out. To those Christians who had devoted their lives working for the dignity of all God’s children (i.e. social justice), Beck’s remarks seemed utterly ridiculous. Humanity’s biblical calling is clear:

Learn to do right; seek justice.

Defend the oppressed.

Take up the cause of the fatherless;

plead the case of the widow. (Isaiah 1:17)

Many, at the time, were tempted to dismiss Beck’s remarks as the thoughtless rantings of a man apparently unversed in either scripture or theology, a man governed by a self-serving political ideology that actually is incompatible with Christianity. But simply to dismiss his remarks and continue with church-as-usual would be to overlook a deeper, far more troubling trend among Christians today. After the initial fall-out, Beck’s executive producer explained, “Like most Americans, Glenn strongly supports and believes in ‘social justice’ when it is defined as ‘good Christian charity’… Glenn strongly opposes when Rev. Wright and other leaders use ‘social justice’ as a euphemism for their real intention—redistribution of wealth” (ABC World News, March 12, 2010).

___________________________________________

Many of us do not want to ask how our own privatization and a-politicization of faith is a politically-motivated, cultural inheritance—a set of values that permit us to disassociate our faith from consumer practice, voting, conduct in the workplace, treatment of the stranger, and other “public” ethical decisions.

___________________________________________

In other words, once we set aside Beck’s bloated rhetoric (and his own political agenda, including the intent to connect Jeremiah Wright and President Obama), an intellectual distinction emerges—one, I suspect, many Christians support: the distinction between the “good Christian charity” of food banks and clothing drives and the protracted work of analyzing and transforming social systems. The first emphasizes individuals; the second, systems and communities. The first does for; the second, with. The first—as the common saying goes—pulls bodies out of the river; the second, goes upstream and tries to stop the bodies from falling into the river at all. The first is less obvious in its ideological motivations (though it certainly has them); the second is more clearly mired in the complexities of politics, law, and culture. The first tends not to threaten established power; the second, certainly does. The first is why we have homeless shelters and charitable gift deductions; the second is why we have ministries at the United Nations and in Washington, D.C.

For most of Protestant history, Christians have believed that both of these models are important—vital, even, to their faith. In the early 19th century, Christians worked to end slavery, stop alcoholism, advance women’s rights, plead the case of the American Indian, and end poverty, just as they clothed the poor, fed the hungry, and visited the sick. They saw these ministries as inextricably intertwined.[1]

Even then, the reformers had their opponents: people who, for instance, said that the church was a spiritual institution and should not, therefore, get involved in “political” matters like slavery. But beginning in the 20th century, a significant change began to take hold (for reasons explored and identified in this issue of Unbound): social justice started to become a secular affair as Christianity began to confine its attention to the private (supposedly apolitical… or “non-threatening”) matters of spiritual growth and conventional charity.

We, who have inherited the legacy of this separation, understandably wonder why the church has offices in D.C. or at the UN. We bristle when we hear from the pulpit a critique of contemporary capitalism or of an American war. We start getting concerned about the separation of church and state. We fear the pastor is imposing her own political biases. We want faith to be simple. We don’t want to get all tied up in political questions, having to worry about the confusion of authority (Am I being led by scripture or a political party?). Truth be told, we probably do not want to ask how our own privatization and a-politicization of faith is a politically-motivated, cultural inheritance—a set of values that permit us to disassociate our faith from consumer practice, voting, conduct in the workplace, treatment of the stranger, and other “public” ethical decisions.

Well, this issue of Unbound asks that question. Playing on the title of the movie, “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” this issue asks why the church should engage matters deemed “political.” Does the church belong in the public square? And if so, why?

___________________________________________

Playing on the title of the movie, “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” this issue asks why the church should engage matters deemed “political.” Does the church belong in the public square? And if so, why?

___________________________________________

Quick Takes

We start out with some “quick takes.” Here, we record rapid interviews of Christians explaining why they think the church should be “in” the world and what scripture and lived examples they look to.

Renowned social ethicist Gary Dorrien briefly discusses why he is still a Christian, reflecting on the meaning of the Civil Rights Movement for his faith.

Seminary student Emily Morgan reflects on the true spirituality of the church and how, when distorted, the rhetoric of the church’s spirituality (such as used to justify 19th c. neutrality on the issue of slavery) can be co-opted to prevent intervention in the world and to preserve status quo power.

Eleanor Reed Held takes a quick look at the different ways Christians practice church, arguing that practice must extend beyond Sunday morning and pietism, reaching into public life, or what she calls the “second stage.”

Pastor and Co-Moderator of the Presbyterian Peace Fellowship, Roger Scott Powers, describes “Presbyterian Citizens,” remembering that the American Revolution was known as the “Presbyterian rebellion.”

Debating Church in the World

Next, Unbound “debates” why the church should be in the public square, examining scriptural and theological reasons. Starting us off is “Gospeling Beyond Our Preferred Agendas” by past president of the Society of Biblical Literature, Walter Brueggemann, who offers lessons from the prophet Isaiah—that we must “neither privatize evangelism nor claim the autonomy of social action.”

Missiologist Darrell Guder, reflecting on our cultural inheritances, considers what it might take “to merge the priorities of evangelism and social justice into one missional conviction that embodies them both.”

Theologian Cynthia Rigby explicates the concept of “social righteousness” as a public, not just private, characteristic of faith, pointing readers to a few scriptural maps.

Pastor Douglas Mitchell adapts curriculum from a church adult education class to propose that the ministry of social justice can be a disciplined spiritual practice, bringing us into closer, more intimate (and joyful!) relationship with God.

Finally, W. Travis McMaken discusses why he supports the Occupy Wall Street Movement as a Reformed theologian.

Practicing Church in the World

The next section looks at “practicing church in the world”—lived examples of faithful engagement with the public square. Director of the Presbyterian Hunger Program, Ruth Farrell, kicks us off by describing the construction of eco-villages in Haiti, exploring the complexities of mission, and inviting people willing to work with (not for) Haitians to join.

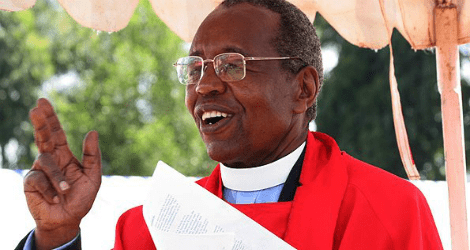

Timothy Njoya, Kenyan pastor and activist, discusses preaching for freedom and equal rights under a repressive regime. Rev. Njoya was detained, brutalized, and tortured for his “seditious” sermons.

For my editorial offering, I discuss the implications of a new e-ministry that has one leg online and the other on the ground (through churches and local organizers). I challenge Unbound and the church to think strategically about being both a citizen and a critic of the emerging e-world, which, along with social media, I liken to the Greek agora—the new public square.

Senior Editor, Chris Iosso, remembers justice and ecumenism advocate Eugene Carson Blake, former President of the NCC, General Secretary to the World Council of Churches, Stated Clerk of the Presbyterian Church, co-author of the 1953 “Letter to Presbyterians” denouncing McCarthyism, and a man once known as the “Protestant Pope.”

Director of the PC(U.S.A.) Office of Public Witness, J. Herbert Nelson II, identifies a new organizing model inviting young adult participation.

Director of the Presbyterian Ministry at the United Nations, W. Mark Koenig, discusses what it means to have a public faith and be global ambassadors for Christ, particularly in the context of the UN.

Paul Seebeck closes this section with a testimony to how Presbyterians are combining evangelical mission and social justice.

Preaching Church in the World

Unbound then reflects with scripture on the rationale for, and meaning behind, the church in the public square. Scholar Margaret Aymer offers one of nine lessons from her Horizons Bible study, Confessing the Beatitudes, and says, Jesus promises sustenance to the famished, but calls the “stuffed” to account.

Pastor Jeffrey Krehbiel provides an excerpt from his book, , looking to Mark 6:30-44 (loaves and fishes) as a model for turning a crowd into a community, organized for leadership, power, and action.

Minister and Coordinator for the Children’s Defense Fund, Shannon Daley-Harris records a sermon, tracing the progress in Isaiah 59 from complaint to confession to calling. The public square—flyered with eviction notices and photos of children gunned down—is, she argues, precisely the kind of place the church belongs—a sacred space.

Finally, Unbound offers resources, recommended readings, and ways to take action as you grow and deepen the public witness (and therefore, spiritual nourishment) of your faith.

____________________

Notes

[1] Timothy L. Smith documents this history well in his book, Revivalism & Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil War (John Hopkins University Press, 1980).

Patrick David Heery, Rev., is the Managing Editor of Unbound. He staffs the Advisory Committee on Social Witness Policy as the Associate for Social Media and Social Witness. He was recently ordained as a Teaching Elder in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and is a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary with a Master of Divinity. He has a Bachelor of Arts in English, and another in Classics, from Ohio University.

Patrick David Heery, Rev., is the Managing Editor of Unbound. He staffs the Advisory Committee on Social Witness Policy as the Associate for Social Media and Social Witness. He was recently ordained as a Teaching Elder in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and is a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary with a Master of Divinity. He has a Bachelor of Arts in English, and another in Classics, from Ohio University.

Unbound Social