The Church’s Witness

At a moment like this, it may be that we are more willing to ask questions that have long engaged the minds of Presbyterians, even if rarely heard in our society at large. When we are stretched to understand how, who and, more deeply, the meaning of it all, perhaps we are better prepared to reconsider the insights and wisdom of our biblical and theological traditions regarding the oikonomia, the economy: its impact on our lives through production, distribution, and consumption behaviors.[xi] As Christians, especially Christians of the Reformed tradition, this may be the moment to reaffirm that the management of our lives through any economy is always part of our response to God’s oikonomia, God’s own work of creation, redemption, and reconciliation. Economic systems are not “laws unto themselves . . . free of religious and moral constraints . . . .”[xii] To believe so is a denial of God’s sovereignty. Our Reformed tradition teaches us that we are called to shape the economic system, as we are called to shape every aspect of our lives, as a service to God. In 1993, the 205th General Assembly reaffirmed this principle:

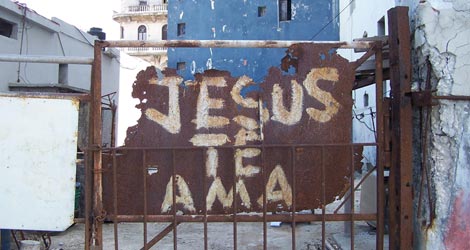

Churches in the Reformed tradition are sustained by worship, make corporate confessions of faith, and are known for their engagement with the public order. This is not without reason. For Reformed Christians, God is at the center of life in all its varied facets. God is active in the world as its creator and redeemer, neither staying on the sidelines nor being contained within certain boundaries. Churches seek to witness to God in public life because God is present there.[xiii]

Therefore, we Presbyterians evaluate any economic system not simply on the basis of the material goods and services it provides, but especially on the basis of its human consequences: what it is doing to people, what it is doing with people, and what it is doing for people, particularly the most vulnerable among us. In our tradition, economic behavior, like all behavior, must be subject to moral scrutiny. For this reason the church must speak to the present economic crisis, to the devastation it has brought, and to the hope to which we bear witness: that in Christ a more just order is arising.

Economics in Biblical and Reformed Traditions

Despite the complexity of modern life, the rise of a global economy, and the invention of financial instruments not fully understood by even the smartest Wall Street inhabitants, the Church continues to speak from its unshakable foundation:

“The earth is the Lord’s and all that is in it, the world, and all those who live in it” (Ps. 24:1, NRSV).

From this foundation, this insistence that all humans belong to God and all creation is owned by God, the Church asserts that the secular economy–the business of production, marketing, distribution, and consumption–exists within and under God’s management. Biblical examples of economic values abound. The Jubilee traditions in Leviticus 25 speak to the social harm caused by unrelieved debt and its resulting servitude. They speak to the response of the righteous. Those who have legally accumulated wealth due to the misfortunes of others area called upon to return it to those families from whom it originally came. Centuries of prophetic indictments of poverty caused by landowners’ abandonment of social responsibilities and absence of compassion equate justice with true knowledge and worship of God (for example, Amos 5:21-24). Jesus describes assistance to the neediest, the sick, the naked, and the imprisoned, as service to the Son of Man (Matt.25:31-46). He proclaims woe to the rich and sated after blessing the poor and hungry (Luke 6:20-26). Biblical economic values demand nothing less than the establishment of economic well-being for all, those present today and those who will follow us, as the purpose of society’s economy and its faithful response to God.

Thus, any economy, regardless of size or form, is judged by its capacity to serve the needs of people, particularly the most vulnerable. This has been the historical witness of the Reformed tradition. For example, the Westminster Larger Catechism interpreted the commandment, “Thou shalt not steal,” to include these positive economic activities:

. . .giving and lending freely according to our abilities and the necessity of others; moderation in our judgments, wills and affections regarding worldly goods; …frugality; and an endeavor by all just and lawful means to procure, preserve and further the wealth and outward estate of others, as well as our own (7.251).[xiv]

In a 21st century response to contemporary lending practices, the 217th General Assembly (2006) stated that “a proper understanding of usury for this (or any other) century will attend to the business practices surrounding lending.” It proposed three criteria for evaluating lending practices: does the law or practice (a) “take advantage of the financial distress of those economically disadvantaged,” (b) “balance the economic benefit of both the lender and the borrower,” and (c) “lead to the conduct of financial transactions in a fair and just manner” including truthfulness, nondiscrimination, full and clear disclosure, and no coercion? [xv] Sadly we recognize the dramatic relevance of these moral principles for our times. Would that the subprime lenders and lax regulators had listened to the church–or that we had spoken more clearly!

In light of growing knowledge about our surrounding physical environment, the church has come to recognize that the gospel’s message of commitment to and responsibility for others exists within the context of earth’s limited capacity to provide resources and reabsorb our wastes. The earth simply cannot sustain itself under the weight of the unlimited consumption and subsequent waste produced by 6.8 billion people. Therefore, a just distribution of material goods and the wealth to acquire them,

. . . put[s] moral limits on economic activity for the sake of human well-being, future generations, and nonhuman life. It calls for a renewed emphasis on the Reformed norm of frugality and lifts up the norm of sufficiency so that all may participate in the ‘good life,’ calling for abundant living in caring communities in a way that is less materialistic and more frugal. [xvi]

A year of revelations about financial arrangements pursued for profit, without regard for risk to individuals and communities, yet rewarded by salaries, bonuses, and stock options beyond the ken of 95 percent of our U.S. households, reveals just how far from the moral standards of frugality and sufficiency our economic practices have drifted.[xvii]

When economic conditions have not been just, the church has spoken out forcefully. The Social Creed of 1908 denounced the appalling conditions of the working poor and demanded a living wage, safe working conditions, the right of all people to self-maintenance, and the “abatement of poverty.”[xviii] In 1996, the 208th General Assembly denounced the very existence of poverty as “… intolerable, a moral scandal of maldistribution and unsustainability, that disregards human dignity, solidarity and equity, as well as ecological integrity.” And, yet, the church confessed with anguish, poverty “has been condoned by churches and societies!”[xix] In 2006 and 2008, the General Assembly adopted Just Globalization and then A Social Creed for the 21st Century, both of which speak to wrongful economic conditions that continue to deny millions basic conditions of dignity while threatening the health of the planet.[xx]

In summary, these two principles, (1) economic justice for all (the establishment of economic conditions that support the human flourishing of all), and (2) sustainability (the establishment of conditions of economic justice today that will not destroy the earth’s capacity to provide abundant life to future generations), remain the basis of the biblical and Reformed imperative to promote social righteousness in economic matters.[xxi] They remain the plumb lines against which economic practices in the 21st century must be judged. They are the product of a way of thinking about God, neighbor, self and all of creation derived from Reformed beliefs and values that refute many economic assumptions and practices commonly accepted by our society today.

Unbound Social