Echoes of Empire in the Immigration Debate.

The people making the decisions about immigration use it as a political contrivance; its solutions in name are solutions to symbolic and electoral problems. Each potential humanizing improvement is met with a provision based on a rollback of reason. Nowhere do we see this more clearly than in the blow-by-blow of how the comprehensive reform bill was gutted; but as is increasingly the case with news from Washington, more facts do not bring new understanding. The Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act’s very existence, pass or fail, signals the rhetorical leap America is taking backward toward the 1850s.

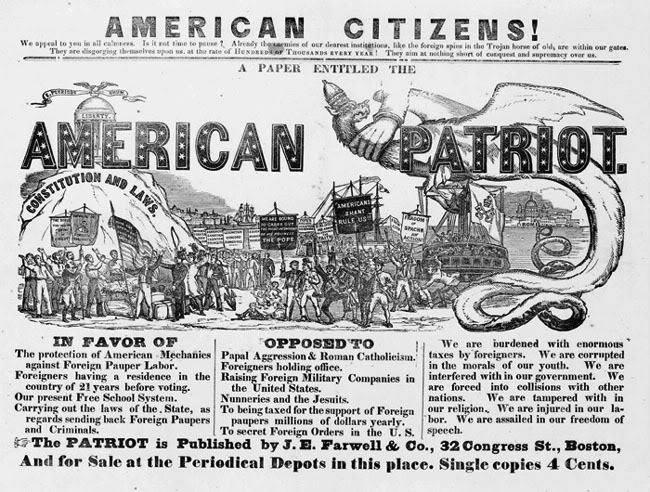

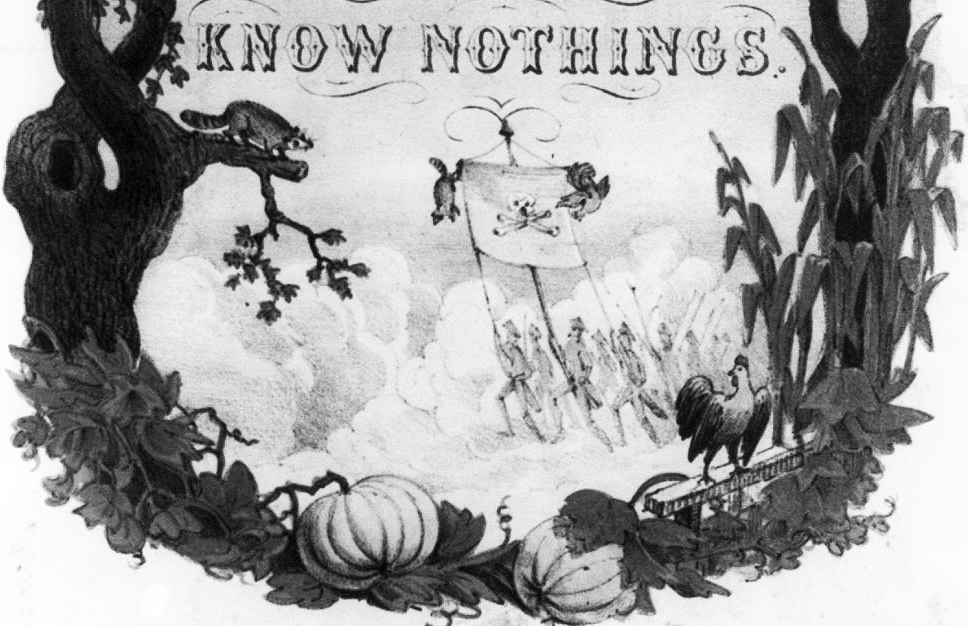

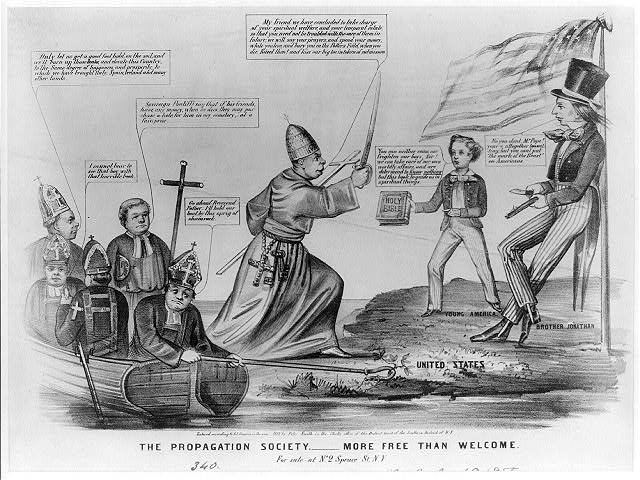

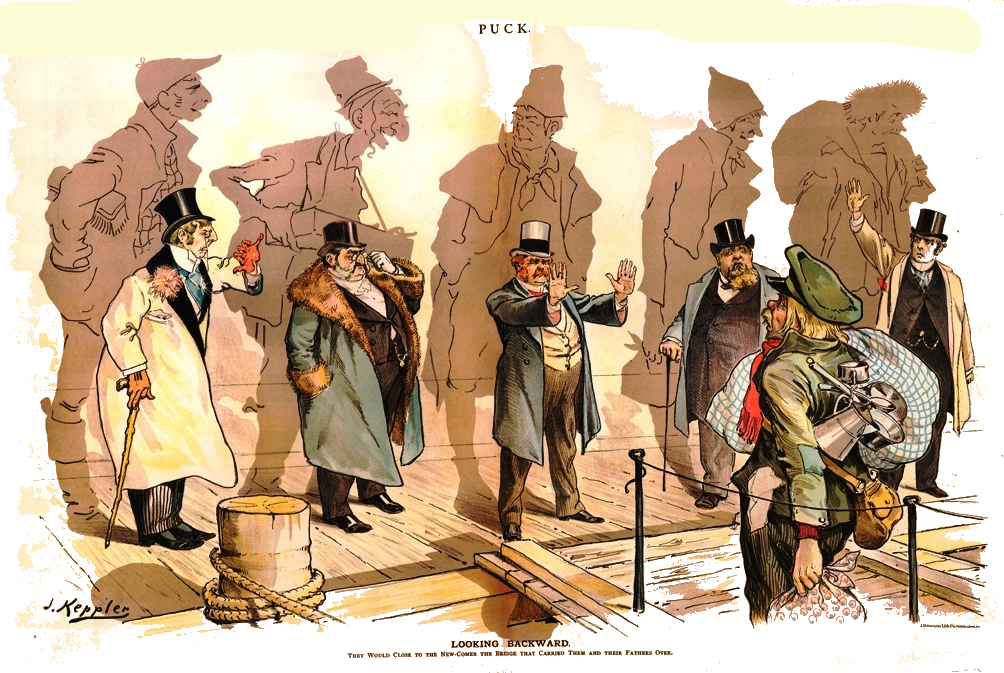

During the 1850s the rules of “acceptable” racism were being debated–not on the matter of slavery, but on the matter of admitting other social inferiors. In that debate we see the codification of white mistrust and the paradoxical exceptionalism that drove Manifest Destiny and created social norms that arguably undergird legal structures to this day. During this period we see a remarkable militaristic expansion of American interests and not coincidentally the emergence a vitriolic “American” party – also known as the “Know Nothings.” The purpose of the Know Nothings was very simple – the radical restriction of American immigration, especially of the flood of Irish immigrants driven to American by the Great Famine. Opposition to Roman Catholicism (and Judaism) of immigrants was part of the picture; Louisville’s riots in 1855 attacked both Catholic Irish and Catholic Germans.

The American Party was a star on the rise during the early middle of the 19th Century, notable for its pro-American platform, an ironic handle given its support for the massive and violent continuation of the Indian removal act of 1830. The Party’s rise was so meteoric, in fact, that only the impending Civil War and the division of the party over the issue of slavery was powerful enough to halt its growth. It was during this period that we see the common contemporary myths emerge: of immigration taking jobs, taking services, taking capital – despite massive evidence to the contrary.

The American Party was a star on the rise during the early middle of the 19th Century, notable for its pro-American platform, an ironic handle given its support for the massive and violent continuation of the Indian removal act of 1830. The Party’s rise was so meteoric, in fact, that only the impending Civil War and the division of the party over the issue of slavery was powerful enough to halt its growth. It was during this period that we see the common contemporary myths emerge: of immigration taking jobs, taking services, taking capital – despite massive evidence to the contrary.

As currently amended, Senate Bill 744 marks a return to fairly overt “nativism,” and is greatly troubling for a number of reasons, not all of them obvious. The first and perhaps foremost concern seems virtually to echo late Roman history, an earlier period of globalization under strain. Consensus is building among historians that the problem of defending and controlling its borders was ultimately the final straw for that empire. Its paranoia and militarism in immigration policy proved to be a millstone around the imperial neck. It had become harder to rule the world from a single geographic center of power. Even the Roman emperors Theodosius and Diocletian recognized this dilemma, and tried (ultimately successfully) splitting the Empire into smaller, more manageable kingdoms.

It is instructive to look at the costs of the current bill, as the US taxpayer pays to fight two expensive) wars and to expand dramatically our post WWII intelligence/security establishment, while suffering from a self-perpetuating domestic recession. The issues are related because the economics of foreign policy, much as in Rome’s case, focus fiscal spending on the exterior of the nation, rather than the interior. Obsession with borders, while roads crumble inside – this is a situation for which we have ample precedent. Thus in original form the immigration bill would have saved money:

- During the first 10 years after enactment (2014-2023), the bill would reduce the federal deficit by $175 billion, even after accounting for added border-security and immigration-enforcement spending of $22 billion.

- During the second 10-year period after enactment (2024-2033), the bill would reduce the federal deficit by roughly $665 billion, after accounting for border-security and immigration-enforcement spending of somewhere between $20 billion and $25 billion.

- The net result would be net deficit reduction of at least $840 billion over the two decades following enactment of the law.

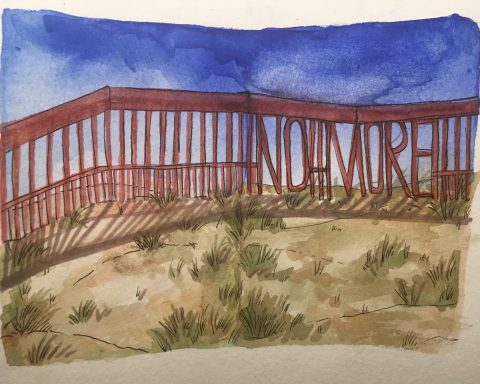

Those projected savings were enormously reduced by the Corker-Hoeven Amendment to the bill– a “stealth amendment” that used the same reliance on lawmakers not reading bills that has become commonplace. This amendment adds $46 billion to the $18 billion we currently spend on “20,000 more border patrol agents, increased drone surveillance and completion of 700 miles of border fencing” despite immigration infractions being at a historic 40 year low.

That $46 billion does not include the human cost, or the actual economic pressures created by American business interests that contribute to illegal immigration. In the Roman republic and the early American republic, repeated economic and military successes drove immigration to overwhelming, society-transforming fever pitches, but left the original or native inhabitants (often virtually “outsiders”) fighting for their place in a world shifting beneath their feet.

That $46 billion does not include the human cost, or the actual economic pressures created by American business interests that contribute to illegal immigration. In the Roman republic and the early American republic, repeated economic and military successes drove immigration to overwhelming, society-transforming fever pitches, but left the original or native inhabitants (often virtually “outsiders”) fighting for their place in a world shifting beneath their feet.

The irony of unfettered economic growth is that it outstrips cultural growth and displaces the original beneficiaries of the policies – i.e. the American Middle Class. Although the American middle class is composed largely of the previous waves of immigrants from the turn-of-the-last-century expansion and earlier, it is no surprise that many worry about the costs and benefits given to the newcomers. Ironically, the militarized border costs larded onto the Senate immigration bill will likely cost more than immigrant healthcare, education and social services (off-set already by all the Social Security benefits the undocumented do not collect). The belief that technology can solve a human problem has escalated this debate. We can now fly drones over the border in constant rotation, therefore the solution, heretofore unseen, is to fly drones over the border. It is technocratic, remote, and the absolute hallmark of imperial thinking.

Indeed, one of the indicators of declining economic health in both societies is how quickly and comprehensively norms previously considered necessary mere years prior can be forgotten. Immigration develops societies. Rome’s multiculturalism was so complete that “…Romans had neither racial bigotry nor cultural arrogance; second, Rome’s citizenship policy was so open that the master nation who had built the empire was ultimately dethroned.”

Roman citizenship was so open a process that it was not military control, dynastic legacies, slavery, or religious subjugation that kept the Republic intact. Rather its bedrock commitment to incorporating and including new populations formed the core economic and social mechanism that expanded, enlivened, and enriched the Republic even as it changed into an Empire. The continental expansion of the United States also incorporated a variety of ethnic groups, though European was the preferred place of origin and degree of multi-culturalism– or multi-ethnicity– is very much in contention.

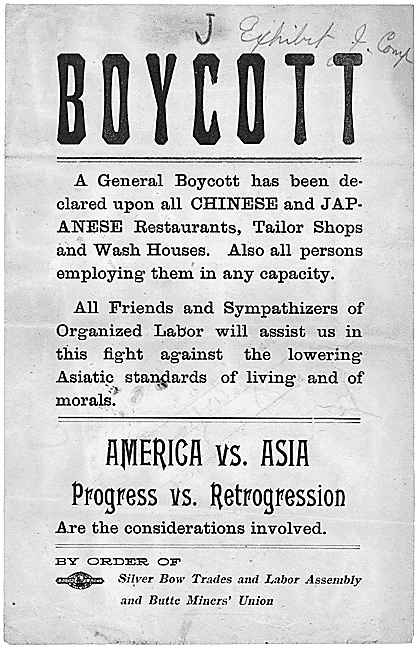

The growth of the American republic included Native American, African- and Asian- American populations in a process characterized by military and economic segregation and discrimination. After America’s 1870’s depression, the subsequent European immigration boom drove the American nation further West into ever richer and more profound dominations of the North American continent. Yet without the earlier Chinese laborers and Irish factory workers, the American industrial revolution and westward expansion would have been over-ambitious dreams.

The usual narrative is that the Romans fell because they devolved from Oligarchic Republic to Military Empire and finally to an economic oligarchy that gutted the merchant or middle class and economic stability quickly departed. Less known is the return of quasi-feudal, racially exclusive, dynastic thinking that reduced Rome’s ability to be a trans-continental engine of economic growth and dispersed prosperity. The American Republic has twice resisted (in the 1860s, and again in 1965) such a reversion. But with our national political divisions at an all time high since the Civil War, that resistance may be coming to an end.

Theologian Wes Howard Brook argues that there are 5 characteristics of an empire:

1. Boundaries – Distinguishing meaningfully between core “internal” space and separate “external” spaces. Guantanamo is an excellent example of an imperial holding that is not empire, as are any of our military bases on foreign soil that operate under “American” home law.

2. Inequality – All transactions are made to favor the Empire, that subordinate states and “partners” receive only through so-called trickle-down benefits.

3. Luck – Rare is the designed Empire. Most empires are happenstance intersections of moments in history and resources to fit those moments. America, in several occasions largely surrounding war, has been extremely lucky and exploded out of 1776 and 1945 to dominate postwar economic conversations.

4.Erosion of values– The ability of an empire to hold true to founding precepts, and indeed any precepts, consistently and with consistent regard for the spirit of those values, declines over time.

5. Suspicion – Agents that are not complicit with the imperial agenda are against the imperial agenda. “Over time it’s going to be important for nations to know they will be held accountable for inactivity,” he (Pres. George W. Bush) said. “You’re either with us or against us in the fight against terror.”

The outsourcing of manufacturing, the exporting of white-collar jobs, the increasing reliance on computers, and the global recession have all taken a massive toll on America, to the point that in one human lifespan, the American dream has virtually died. When as many as 80% of younger US citizens will experience significant unemployment in their lifetimes, and economic inequality continues to increase, it is hard to argue that widespread upward mobility can return. Perhaps we can recapture it, but it will require a far more communitarian and sustainable vision– one certainly missing from the defensive and security-bound immigration debate.

Why is immigration such an important part of this conversation? Why does an immigration bill speak to our national character on the same scale as a war in Afghanistan? Because both acts, on a national level, reveal key thinking in how we, as a people, are choosing to solve problems. We are seeing the same dynamic in all forms of debate across the spectrum of American panoply – the dynamic of blame, externalization, and the old and thoroughly discredited notion that size matters. The Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act epitomizes imperial traits – predicated on unequal boundaries, ignoring both past values and the role of chance, informed wholly by suspicion.

Why is immigration such an important part of this conversation? Why does an immigration bill speak to our national character on the same scale as a war in Afghanistan? Because both acts, on a national level, reveal key thinking in how we, as a people, are choosing to solve problems. We are seeing the same dynamic in all forms of debate across the spectrum of American panoply – the dynamic of blame, externalization, and the old and thoroughly discredited notion that size matters. The Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act epitomizes imperial traits – predicated on unequal boundaries, ignoring both past values and the role of chance, informed wholly by suspicion.

The Know-Nothings were given their name ironically. It does not refer to their stupidity, but is rather an indication of their early, clandestine origins. In the title I use it somewhat ironically. Our current immigration debate has become divorced from two important kinds of facts. The first is simply basic mathematics. We cannot afford, morally or economically, such an egregious expansion of law enforcement into a problem that is less of a problem every day. The second are the facts of history. Everything we try, has been tried before. We are not the first to have innovative technological solutions. Our leadership is on a 2-year election cycle, and has no motivation to fix anything. They understand what kings and generals before them very well – people do not like to change leadership in a crisis, so the manufacture of crisis becomes the role of leadership.

Our know-nothings have remarkably similar values to the originals, which is precisely where the problem originates. The moral evolution of this form of conservatism is nonexistent. It is an old, reptilian core of the brain, the one that fears change and is incapable of taking responsibility. It is the opposite of the message of any faith tradition, especially the Christianity so many of our current know-nothings purport to follow.

We must recognize that our variable definitions of the divine in people do not undercut the existence of that divinity in others. Our core religious traditions are founded on immigrants, strangers, and outsiders interacting with a system of power and demonstrating values of community, love, and respect. The Christian narrative is in many ways the ultimate immigrant story, but we too have now become the creaking bones of empire, withdrawing into reflexive conservatism as racially, theologically, and economically the power slips from our fingers. We rush into new territory, hastily erect new settlements to the dismay of old occupants, bring all our power to bear on making the structures of power favor our mandate, and patronize client agents for our own benefit.

The Christian narrative has become for many an imperial doctrine that mirrors the political changes in this country – which is why so much of our spiritual entitlement seems inevitable, natural. Church is rarely a body that stands up to people of power, but seems to have regressed to the role of a series of well-organized streetcorner preachers – each calling in very quiet voices for people to be nice to one another, while action becomes the role of “advocates” somewhere else, or week-long “moments for mission.” We have, not without irony, outsourced our moral decision-making to central structures of power that help alleviate the terrible burden of actually having to consistently face thorny problems like immigration head-on. Which may be why PCUSA has some truly excellent advocacy positions – while even congregations that support those positions often find it hard to integrate newcomers.

Immigration is, fundamentally, encountering the other. More than war or peace, immigration speaks to our default setting – who are we when the newness arrives? There can be no better reflection of our theological, spiritual, and moral values than examining how we, as a community, have chosen to address the other on a policy level. And we are failing comprehensively.

As people of faith, our role in this conversation is to point to the moral dynamics within the debate. If our goal is the restoration of a kind of moral authority our country has not possessed since the Second World War, we should recognize the role that broadening immigration played in that global reputation. Where we were once greatly respected, we are now merely powerful. Where we were once proud to be a nation of immigrants, too many seem fearful of an imagined invasion. And where we were once the land of opportunity, we are now the land of denial.

______

Rob Moore is a gardener, hiker, and website ninja. He also is the interim editor of Unbound.

Unbound Social