The words “settlers” and “territories” harken back to the earliest stories that came from the Europeans who sailed to the “New World.” They have complicated histories which go back to our nation’s original sins of slavery and the genocide of indigenous peoples. But Americans don’t have a monopoly on these words and concepts. By the end of the 19th century, the world had been carved up into colonies and “territories” by the empires of the “Age of Discovery,” with much of Africa, Asia, and South America going to European powers, Russia spreading east, and the US spreading west. By 1900, it seemed that the age of the “open frontier” had come to an end. At the end of World War II, as the empires of the past began granting their subjects independence, colonialism took on new life in what we know as The Holy Land.

When Israel was established in 1948, its first Prime Minister, David Ben Gurion, knew that Israel faced a trilemma. The Zionists’ aim was threefold: to have a state that would be Jewish, democratic, and on all the land “between the river and the sea.” The primary founding father of Israel understood even back then that Israel could have only two of these three aims at the same time.

If Israel were to include all the land between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean, it would come with a large population of Palestinians, making a Jewish-majority state impossible. If Israel was to be on all the land of historic Palestine (with all its people) and declared as a Jewish state (privileging Jews), then Israel would not be a democracy. Finally, if Israel took some of the land with as few Palestinians as possible, it could be a democratic, Jewish state because the Jewish Israelis would outnumber the Palestinians who would be absorbed.

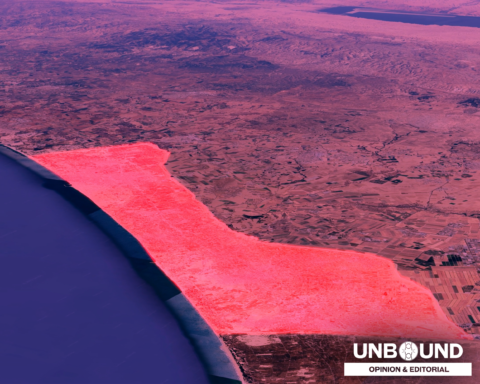

Ben Gurion and the Zionist Movement chose the third option: a democratic Jewish state on some of the land with as few Palestinians as possible. Seventy years on, the original trilemma, which never went away, is coming into sharper focus. The Palestinian population has outpaced Jewish growth, and Israel has had control over all of historic Palestine since 1967 when it conquered the remaining land left by Ben Gurion. Today, the Jewish and Palestinian populations are almost even, but the Israeli government exercises complete control over both. There is talk of annexation of the most arable land (the stretch along the Jordan River Valley) where through military might, Israel has held the numbers of Palestinians to a minimum.

The recent Israeli election denied millions of Palestinians the vote. Only those who live within the 1948 borders have that right. Most Palestinians are disenfranchised because they are not citizens of Israel; they are subjects. This is a colonial term because Israel is a colonial power. Further, Israeli historian Ilan Pappe has said that Israeli settlement of Palestinian Territories was never an occupation; he calls it Settler Colonialism. As in other colonial examples over history, a large swath of people under Israeli control have no self-determination, even though a minority of Palestinians (and descendants) who happened to be “absorbed” have representation in the Israeli Knesset.

Those disenfranchised Palestinian subjects have made real the dreaded scenario that Ben Gurion wanted to avoid, because in spite of all the propaganda otherwise, they render Israel not a democracy.[1] Today, Israel is a Jewish state that privileges Jews. In 2017, the United Nations issued a report calling Israel an apartheid state. There is no mistaking the similarities between the Palestinian Territories and South African bantustans where the colonizers devised similar laws and brutal measures to maintain physical separation and vast inequality between themselves and the indigenous people. As a result, Israel has lived out its original trilemma into the worst possible outcome.

Such a trilemma is not unique to Israel. When the US started growing its borders, the trilemma that came into focus was whether the nation would remain a republic, keep power in the hands of white settlers, and continue to expand its territory, absorbing (non-white) peoples as full citizens. By 1898 when the westward expansion was complete and the US took the Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines, and Guam after the Spanish-American War, there was a heated debate over becoming an empire rather than a republic because 8 million brown people came with those acquisitions.

In his book How to Hide an Empire, historian Daniel Immerwahr writes, “In essence, it was an argument about a trilemma. Republicanism, white supremacy, and overseas expansion—the country could have at most two. In the past, republicanism and white supremacy had been jointly maintained by carefully shaping the country’s borders. But absorbing populous non-white colonies would wreck all that.”[2] Immerwahr says it was no accident that white settlers remained the majority of the population. He writes,

The Mexican War of 1846–48 had ended with U.S. forces occupying Mexico City. Some in Congress proposed taking all of Mexico. From a military perspective, that was entirely feasible. But South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun, one of the nation’s prime defenders of slavery, objected. “We have never dreamt of incorporating into the Union any but the Caucasian race—the free white race,” he insisted on the Senate floor. “Are we to associate with ourselves, as equals, companions, and fellow-citizens, the Indians and mixed races of Mexico?” Apparently not. The United States annexed the thinly populated northern part of Mexico (including present-day California, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona) but let the populous southern part go. This carefully drawn border gave the United States, as one newspaper put it, ‘all the territory of value that we can get without taking the people.’[3]

These jarring words are reminiscent of the Zionist myth propagated throughout the 20th century that Israel was established on “a land without a people for a people without a land.” It is eerie to read Palestinian lawyer Raja Shehadeh’s September 2019 opinion column in the New York Times entitled, “Israel Wants Palestine’s Land, but Not Its People.” Shehadeh says “Israel already is reaping all the benefits of annexation in the West Bank, and without having to bear any responsibility for the welfare of the Palestinians living here.”

Americans like to think of having shared values with Israel, hence seeing it as a natural ally. There is a lot that the US shares with Israel. And it’s not all good. The parallels of taking land and rejecting the native populations are only the tip of the iceberg.

When Jewish settlers started moving into the “Palestinian Territory” of the West Bank after Israel took those lands following the 1967 War, the Jewish settlers were subsidized by the Israeli government and were classified as economic settlers needing access to cheaper housing. Over the years, as taking other peoples’ land became harder and uglier, the settlers who did the toughest expropriation have been religious ideological settlers. Numbers of ideological settlers from places like Brooklyn, NY, grew in leaps and bounds. And the Israeli military accompanies them and defends their right to forcibly expropriate the land rather than defend the Palestinian landowners.

Fifty years on, the city of al-Khalil, or Hebron, as the settlers call it, is a horrifying example of what happens when a military force enables a small group of extremist settlers to take what they want and deprive the indigenous people of their land and rights. With the continuous support of the Israeli military, fewer than 1,000 settlers have been squatting in the center of a city of 200,000+ Palestinians, making their daily lives a living hell. As the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem describes it,

[Israel] has imposed physical and legal segregation between the hundreds of settlers and the thousands of Palestinian residents. Palestinians are subjected to extreme movement restrictions, and hundreds of businesses were shut down. This, coupled with violence by settlers and security forces, has made life intolerable for Palestinians, leading to a mass exodus and the economic ruin of the downtown area. Israeli authorities thereby promote the driving out of Palestinians from Hebron’s city center.

In the US example, it is no less repugnant. Immerwahr’s account of how white settlers overran the continent is alarming:

“The growth of the white population was like a flash of dynamite, and it would explode the founders’ vision of the country. The great Jeffersonian system that had prevailed in the first decades, with western subjects semi-colonized, simply could not hold. There were too many Daniel Boones. The government gave up prosecuting squatters by the 1830s and instead let them buy their land. In the 1860s it began giving away parcels of public land as ‘homesteads’ to nearly any citizen willing to live on them. The territories with large white populations became states swiftly….

The culture changed, too… settlers acquired a new identity: pioneers… they were the proud flag-bearers of a dynamic nation…. In 1845 the United States Magazine and Democratic Review coined an indelible phrase and captured the prevailing mood when it wrote of the nation’s ‘manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.’[4]

Manifest Destiny provided the permission slip to white settlers who rapidly conquered a continent. It was derived from the Doctrine of Discovery which emerged from a 1493 Papal Bull which declared any non-Christian land as available to be “discovered, claimed, and exploited by Christian rulers.” Named or unnamed, this doctrine stands at the origin of all European claims in the Americas and justified the western expansion of the United States. After the Reformation, Protestant settlers took this Christian doctrine to a higher level. Its relevance now, as Christian ethicist Walt Davis observes, is that “it reinforced the dehumanization of many (Native Americans, Africans, Jews, Arabs, et al) and contributes to the ideology of White Nationalism today.”[5] The standout tenet of Manifest Destiny is a God-given mission to redeem and remake “uncivilized peoples,” with white settlers as God’s Chosen People. This had devastating consequences for the native populations, bringing them to a 90% decline by 1800.

Chosen-ness and exceptionalism are no strangers to ideological Jewish settlers in the West Bank. Some of the most militant settlers use biblical justification for taking land from Palestinian owners, some with deeds going back centuries. Israel’s Open Fire Policy “allows unjustified use of lethal force, conveys Israel’s deep disregard for the lives of Palestinians and facilitates Israel’s continued violent control over millions of Palestinians,” says B’Tselem. Regulations “meant to prevent unnecessary harm to life and limb, have failed to prevent the killing of thousands of Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip – partly because they are repeatedly violated, sometimes on the orders of senior ranking officers or with their consent.”[6]

As Palestinians continue to resist the military might of an insatiable settler nation, can the expansion of Israeli settlers be contained so that both peoples can share the land with equal rights and equal promise? There is a way out of the trilemma facing Israel today. That option is equal treatment under the law for all the people “between the river and the sea.”

Now that Israel has taken control of all the land of historic Palestine, including a population of millions of Palestinians, it is clear that inherent in the concept of a Jewish state is the exceptionalizing of Jewish citizens which has resulted in an unequal apartheid system of government. It is time for Israel to grant all its Palestinian subjects equal rights. Many fear that abandoning the “Jewish state” concept will “destroy Israel.” The example of South Africa is instructive; White South Africans were also liberated when apartheid ended. Dismantling an unequal political regime will in fact strengthen and revitalize a just Israel in which Jewish Israelis and Christian and Muslim Palestinians can bravely move into a new future together. And here in the United States, deep-set racism has been unmasked by White Nationalists marching in our streets shamelessly yelling Nazi chants.[7] We need to be alarmed by this unambiguous, overt racism. Our only way out of our trilemma is to jettison White Supremacy along with the Doctrine of Discovery that enabled it. We too must embrace true equal rights for all, without exceptionalism for the descendants of white settlers who still claim superiority over those parents being separated from their children at our southern border.

[1] “No matter how many Palestinians vote in Israeli elections, we still can’t win.” Henriette Chacar, September 20, 2019, The Washington Post.

[2] Immerwahr, Daniel. How to Hide an Empire, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, p. 80.

[3] Ibid, p. 77

[4] Ibid, p. 35

[5] Workshop slides at Presbyterian Big Tent, Baltimore, MD, August 2019.

[6] btselem.org/topic/firearms

[7] “’Blood and soil’: Protesters chant Nazi slogan in Charlottesville” – Meg Wagner, CNN, August 12, 2017

Noushin Framke is a Presbyterian ruling elder and writer/editor who has won the Award of Excellence from the Associated Church Press for her writing. She was on the writing and editing teams of Steadfast Hope (2009), Zionism Unsettled (2014), and Why Palestine Matters, the Struggle to End Colonialism (2018), all publications of the Israel Palestine Mission Network of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).

Unbound Social