Resurrection in a Broken World

Henry Koenig Stone

What does resurrection mean in a broken world?

Events in this last week have me rethinking the place that resurrection takes in my personal theology. I am far from convinced that the length of a life in any way measures its value.

Some of this insight comes from the varying ways that people are responding to the fire at Notre Dame. Some simply mourn, adding the loss of a monument to the stress of a time with political and social turmoil. Some grieve instead that “we have resources and righteous rage to expend on the rebuilding of buildings and yet barely notice that the church is in ruins”, as the Rev. Traci Blackmon writes on Twitter. A follower agrees: “Where is the energy to rebuild communities?” Others skip the public grief, and jump right into fundraising for the cathedral’s restoration.

Having been once in that beautiful space, my first reaction to the public statements that “we will rebuild” is to be filled with hope at the idea that such an important historical and cultural landmark may be restored. But I think we might be able do something far more impactful. To me, jumping right into repairs for the cathedral without considering the context of the broken world around it is a little like saying “I’ve been born again” without also considering what God’s transformation of our lives would actually look like. Theologically, it is dangerous to skip Lent and go straight to Easter.

In the resurrection of the cathedral, there is an almost implied outcome that it not be accompanied by any sort of transformation. The goal, after all, would be to “restore” the building to its former state. But there is an opportunity to learn from this organization of people toward a common purpose–to use a moment of death and rebirth to draw attention to other parts of the narrative. To recognize the favoritism in seeing a western monument to one view of God as essential while ignoring burnt black churches and nearly ignoring coverage of the (contained) fire at the Al-Aqsa Mosque.

We are seeing that double standard take at least a few steps toward unraveling: after the Notre Dame fire got people’s attention, there are reports of donations rising for the three black churches that were recently burned by a white supremacist.

But this isn’t a feel-good story, because donating to those black churches does not fix the larger brokenness of our world. Much as with Notre Dame, fixing those buildings will not heal the damage of racism and white supremacy. As the waters rise and American cities shore up their defenses against the sea, those crucial self-protective actions will not erase the disproportionate impacts of climate change on people who live at the margins already—often people of color. And no matter how valiantly doctors fight to extend our lives, an extra year is little compared to the overall effect our lives have on those around us.

___________________________________________

If Christ is raised to life eternal, and we are not changed by it, then what’s the point?

___________________________________________

Why do we tell the story of Jesus’ resurrection? Perhaps it’s just because we fear death and value our life. But to me, that’s not enough of a reason. For me, the Easter story signals that Jesus’ transformative message is more possible than we might otherwise believe–that justice and love have greater staying force than the Powers That Be. Last week, I lost a dear friend and mentor at too young an age. Maundy Thursday would have been her birthday. But Glenda’s effect on my life will never leave me. The sermons she preached and the conversations we shared called me into closer relationship with the world.

Perhaps the Acts of Power that we report in the Bible–healing the blind, curing the lame, and yes, raising the dead–are meant to do the same thing. Perhaps they have greater significance than displaying some magical force that guarantees security. Perhaps the stories of those acts are meant to recall us to life–different life, connectional life, that can change the world. Resurrection takes us into the realm of the unexpected.

As I reflect on the cloud of witnesses who have passed in recent years, it seems that the value of their lives is not bounded by whether or not they live on in some physical or metaphysical realm. Their resurrection is more universal than my own Christian theology. They are recalled to life in every way that their living actions, relationships, and senses of justice provided opportunities to transform the world. In that way, they are much like Jesus. Because although we will soon tell the story of the empty tomb, the impact of the resurrection lies more tangibly in the acts of Jesus’ disciples.

May they be acts of transformation. Because if Christ is raised to life eternal, and we are not changed by it, then what’s the point?

Resurrection and Judgment Revealed—Notre Dame, Mueller, and Sudan

Chris Iosso

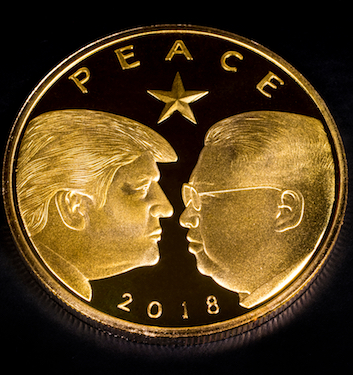

The Mueller report—minus as much cover-up as possible—will be on many worshippers’ minds this weekend. How much will ego and power continue to obstruct justice?

Also on people’s minds will be the Notre Dame Cathedral fire—fear of every church building trustee. All church buildings are symbolic, but that edifice can speak to Europe’s Christian heritage, the state of Roman Catholicism, and the “spirit” of the French nation/state, which largely maintains the building.

So, too, will be the fate of families on the US/Mexico border, with the Trump Administration trying to be as brutal as possible to deter people fleeing for their lives. How many children will be abused while separated from their parents, especially if Attorney General Barr can jail adults until distant hearing dates? The normal process of worship should lift up those children and every person’s own concerns of the heart, even if we try to block out politics and current events from our Easter services.

But let us not shrink the scope of Christ’s resurrection to a church-world and worship time. Does the resurrection not illuminate all other events? God is at work in the world. God’s purposes, confirmed in the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, are to break the powers of sin and evil and make our hearts and communities into temples of God’s Spirit. For me, the resurrection fulfills an eternal pattern in human consciousness—and unconsciousness– that seeks new life even in the face of crucifixion. For others less tied to the Bible’s Holy Week story, resurrection is about the triumph of love over death. The scary genius of the Christian faith is that we find God’s presence in so many human manifestations.

The human Jesus will be present in the narratives that we now read as if resurrection were inevitable. And yes, he will have been transformed and not resuscitated; his new being is not clearly described in the New Testament texts, but he is recognizable—whether in the form of a gardener, a traveler to Emmaus, a figure on a shoreline cooking fish… He may come to us as “One Unknown,” to quote Albert Schweitzer, but we meet him in the encounter when we know simultaneously that God knows us. The Gospel stories disclose new depths at every reading, reading us in judgment as well as grace, revealing truth within surprise as much as certainty.

To look at the Notre Dame fire with resurrection in the background is not to confuse it with the reconstruction of the damaged building, though President Macron’s promise of rebuilding is important. Many of the symbols and historic associations of the Cathedral are worthy and inspiring, both for the French and people around the world. Still, the expenditure of national funds must be justified for reasons beyond nationalism, given the range of needs a public budget must meet, and the struggles that cross national lines. That marvelous artwork and time-machine cannot be either a patriotic prop or—and this is a Protestant writing—a sacrament in itself.

No church building is the church, which is the gathered people of God. The church was singing and praying in the streets around the burning cathedral. Much of the commentary had to do with the juxtaposition of the devotion of the people who built the cathedral and the neglect that apparently allowed for such vulnerability to fire. The Holy Week timing of the fire makes for inevitable contrasts with both the suffering and dying of Christ and then with the state of the church as an institution. A cathedral’s size and shape reflects medieval Catholicism’s hierarchies, pilgrimages, and need for sub-chapels for relics and memorials to saints, not simply the basic idea of communion as a reenacted sacrifice with all the sacred/profane separations. That the capacity to accommodate pilgrims has morphed into the capacity to accommodate tourists is somewhat ironic, not just for the logistics, but theologically.

Again, from a Protestant viewpoint that centers the church as people around a table celebrating the resurrected presence of Jesus as the Christ, emphasizing the joy of redemption over the need for penitence, the tourist and the believer are not entirely strangers. Both are moved by awe at the scale and imagery embodied in cathedrals. Cathedrals represent a heavenly world full of beauty, even if the cross and stations of the cross also clearly present torture, horrifying pain, and death. Most tourists who go Notre Dame, sometimes many times in their lives, want to be touched and taken out of themselves, at least for a little while. The tourist may want to consume; the believer, commune, but for each the cathedral carries a teaching, witnessing, and unifying function.

With regard to the French nation, the cathedral points to its need for a country to have a purpose beyond itself. Admittedly, this is to claim a more enlightened purpose than that of continent-wide empire that Napoleon claimed in 1804, crowning himself to reject the church’s authority. Does such an encompassing building not point to the sovereignty of God above all nations, and by its long history does it not resist cooptation by any particular generation, bishop, or president? Some Protestant traditions were wrong to dispense too quickly with the good power of images and culture more broadly; not all icons are idols. Here is the French theologian Jacques Maritain prefacing a picture book on cathedrals just as France was being liberated in late 1944:

“So striking a sequence of masterpieces of imagination and reason embodied in stone is an admirable and incomparably pure image of the spirit of France and of the patient labor which, pursued through the centuries, led to the formation of a treasure of civilization, beauty, fortitude and grace unparalleled in the world. …. Meditation over your book will inspire the thought that from this country and this people we may expect new masterpieces, to be born of the sufferings generously assumed for the cause of freedom and honor during an ordeal unequalled in the history of France and overcome by dint of heroism.”

(Alexander Frenkley, Stones of Glory—Stones of France, October 1944; page 1 letter by Jacques Maritain)

That such a masterpiece could catch fire is then a great warning to any culture or nation that would make of its symbol an idol, implicitly idolizing itself. That vulnerability pulls a response of sympathy from almost everyone, even in the former colonies—the test is to remember that universal moment of emotional and even spiritual unity. Do we remember the fire-bombing of the Dresden Cathedral in Germany, painstakingly rebuilt many years after the war? What about the Muslim holy places destroyed or damaged in Iraq and Syria over the past 15 years, the Buddha statues blown up by the Taliban, or separate from war, the burning of Brazil’s National Museum?.

At the same time, the lesson must be that the virtues and future “masterpieces,” and faith itself, resides in people. Jesus’ resurrection was a revelation of the work of the Holy Spirit. That Spirit’s work continues to be identified in the Bible and in the church. Each time we are raised up from despair, grave doubt, or suffering we experience some of that resurrection ourselves.

The Mueller Report, just now being read, will be to some a fire of judgment and others a revelation of how much rot lies behind those grand national facades in Washington, DC. Some will hide behind legal fig leaves, others will lash out, blame others, and distract. The overall message is that our system is deeply vulnerable to human fallibility, corruption, and the lowering of standards. The question is how deeply entrenched authoritarianism may be, for example, if we find judges and courts as jerrymandered as some state legislatures and federal agencies acting unaccountably. Does the report show a government concerned for anything but its own power?

If a political system is to remain democratic, it must involve all the people in understanding and deliberating over as true a set of facts as possible. No individual can be a judge in his or her own case. To the extent that those persons investigated by Mueller control access to or outcomes of the results of the investigation, they and/or the process are corrupt. That Mueller never was able to interview the President, under oath, seems to undercut the claim that no one is above the law.

Every Protestant Christian, and certainly most Catholic and Orthodox Christians, must worry about authoritarianism, in church, state, corporation, or any other form. “Judgment begins in the house of the Lord”—repentance, self-criticism, and restorative and reconciling actions are essential to spiritual health. Rebuilding national trust may be harder than rebuilding a cathedral.

This brings us to Sudan. Most US media have said very little about the massive protests in Khartoum against the now-deposed 30-year dictator, Omar al-Bashir. Long considered a war criminal for his government’s brutal attacks—sometimes via proxies—on the people of Darfur and the Southern provinces that became South Sudan, he was compared to a spider in a web of spies, able to head off any challenges to his rule. Recently, however, hundreds of thousands of people held non-violent protests, multi-day rallies and sit-ins, finally driving his associates in the military to take him out of power. They stayed on the streets to ensure that one of his military entourage would not simply replace him. At one point a Sudanese cabbie had the volume cranked up on his cell-phone and I was able to feel, across the sea of protestors singing, across the thousands of miles of cyberspace, the enormous energy of freedom being claimed.

Some say there is an authoritarian trend in many countries today, propelled sometimes by anti-immigrant resentment and racism. Theologically, those are fallen powers, ideologies that justify layers of violence and abandonment. To see the people in Sudan—and in Algeria—rise up, and stay up and out on the street, till authority can be taken back from dictators long in power, this may be both harder and easier than rebuilding a cathedral. Harder, because for 30 years no one knew who they could trust. But easier perhaps because the lines became clearer and the spirit of their democratic protest sacrament unmistakable.

The resurrection cannot be understood fully without understanding the crucifixion, and we understand both by analogies, examples, and experiences in our own lives. Christians came to see the cross, instrument of judgment and condemnation, as sign of suffering love. For those who live by condemnation, the resurrection is a threat that the truth will emerge and be vindicated. May it be so!

***

Author Bios: Henry Koenig Stone and Chris Iosso serve in Louisville, KY as Managing Editor and Senior Editor of Unbound. Chris also staffs the Advisory Committe on Social Witness Policy as Coordinator, while Henry assists as Associate for Young Adult Social Witness.

Unbound Social