I did not grow up Presbyterian, and I can’t identify as a ‘cradle’ or ‘prenatal’ Presbyterian, or any of the ways that I have heard born-and-bred Presbyterians describe themselves in order to firmly establish their Presbyterian street cred. No, as my longtime Presbyterian pastor once told my Committee on the Preparation for Ministry (CPM), “Kerri chooses to be Presbyterian.”

My pastor and I used to argue about the nuance of “chooses.” Not only am I Presbyterian, but I am also firmly Reformed and unabashedly Calvinist. So, although I chose to become a member of my hometown church of Dayton Avenue Presbyterian Church in St. Paul, MN, I also believe that God’s providence led me to that particular community of faith and this particular tradition. Presbyterianism chose me.

As one who had a first career working in politics and government, the structure of Presbyterian governance is familiar and comfortable to me. Like the “checks and balances” of our republic, I firmly believe in the mutual accountability and responsibility of our polity. The Reformed belief that there is a God who is active in all spheres of life, including the social polis, and that we are called to be actively engaged as a faithful response, resonated with me in the core of my being. So although I have never set foot in Montreat and I don’t identify as one of the “frozen chosen,” I am thoroughly Presbyterian.

___________________________________________

Three years ago, I left a congregation where I was serving as a pastor after a ruling elder told me that they hated the black race.

___________________________________________

I hold a deep affection for and value my relationship with the Reformed Tradition, for Presbyterianism, and for our denomination. This is why it is particularly painful that I have not felt comfortable worshiping on a regular basis in a Presbyterian church for the past three years.

Three years ago, I left a congregation where I was serving as a pastor after a ruling elder told me that they hated the black race.

Three years ago, I left a congregation where I was serving as a pastor after a ruling elder told me that they hated the black race.

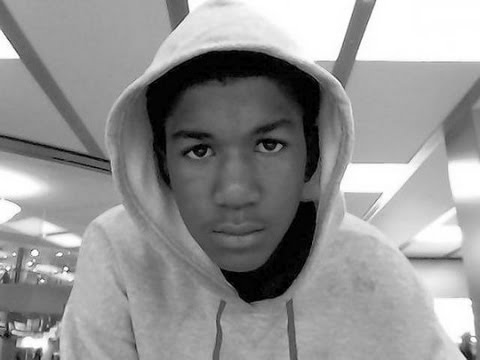

This took place after I preached a sermon on Trayvon Martin and the injustice of the George Zimmerman verdict. I spoke of the pervasive racism in our nation and how that manifests in violence, particularly against black boys. I invited the congregation to view the humanity of Martin and little black boys in general. I preached, “Trayvon Martin. Murdered. Dead. Gone. Robbed of the chance for the hints of responsibility to grow, slowly, fitfully, slowly, painfully into glimpses, and then flashes, then bursts of adulthood. Robbed of the chance to grow into adulthood.”

Perhaps naively, I never imagined that a sermon would cause such an uproar. But a handful of congregants got upset and contacted the senior pastor. One man even met with the session to complain that he had gone back and re-listened to the recordings of all of my sermons and that I preached on the subject of race “all of the time.”

___________________________________________

Perhaps especially, I was embarrassed that those in the majority sat in silence and did nothing.

___________________________________________

I was never told who these individuals were. The senior pastor didn’t think I needed to know. The session received complaints and never discussed them with me. I was told that people were offended because they felt like I had called them racist and that I couldn’t serve in “this type of congregation” in the PC(USA) and “preach a sermon like that.” Even after I was confronted by a member telling me about their hatred of African Americans, the congregation was somehow the victim of my sermon.

Perhaps you think this is an isolated incident. Yet daily, someone shares something racially hateful with a pastor who simply nods and agrees. This type of emotional violence is inflicted upon blacks within our denomination with an unexamined and sinful regularity. It is a sin that is usually perpetuated by the most well-meaning and seemingly good people. It is the passive sin of silence and inaction, of paralyzation, and even laziness.

In January 2015, the Special Offerings Office wasn’t trying to be malicious when they went forward with an “edgy” ad campaign that was roundly criticized as racist and insensitive. The offering campaign utilized troubling and stereotyped images of young children of color, even after being warned by the Advocacy Committees, ministry staff, and others that the ads were racist and unavoidably reinforced the stereotypes used.

Last summer at Montreat Conference Center, Presbyterians gathered to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of King’s visit to the Conference Center in a gathering called, “Martin Luther King Jr.’s Unfinished Agenda.” In the midst of a worship service in which the nine victims of the Charleston terrorist attack were remembered by name, a teaching elder yelled out, “Dylann Roof, say his name!” Yes, as Christians we affirm that God’s forgiveness is for all people, but to shout Dylann Roof’s name in a service honoring those he killed sounded like an easy dismissal of the nine victims. It was like shouting “all lives matter” in front of dead black bodies.

___________________________________________

As a confessional tradition, we will never be able to to confront our demons as long as we talk about racism as though it only exists “out there” in the world and not within our own churches and hearts.

___________________________________________

I am thankful that I was not present, but I was still heartbroken by the incident. I felt embarrassment for our denomination. I was horrified that no one from Montreat offered an apology, at least as far as has been reported. Perhaps especially, I was embarrassed that those in the majority sat in silence and did nothing.

These two examples are higher profile, but they are not isolated instances. They are reflective of the daily sins and practices that exist within our very denomination. As a confessional tradition, we will never be able to to confront our demons as long as we talk about racism as though it only exists “out there” in the world and not within our own churches and hearts. Jesus had something to say about ignoring the log in our own eye.

In 1967, an auspice year in American history and the struggle against racism, the United Presbyterian Church ratified a Confession, which nearly fifty years later we in the church must still recollect:

“God has created the peoples of the earth to be one universal family. In his (sic) reconciling love he overcomes the barriers between brothers and sisters and breaks down every form of discrimination based on racial or ethnic difference, real or imaginary. The church is called to bring all people to receive and uphold one another as persons in all relationships of life: in employment, housing, education, leisure, marriage, family, church, and the exercise of political rights. Therefore the church labors for the abolition of all racial discrimination and ministers to those injured by it. Congregations, individuals, or groups of Christians who exclude, dominate, or patronize their fellow Christians, however subtly, resist the Spirit of God and bring contempt on the faith which they profess.” (C67 9.44)

It would do congregations and the denomination well to revisit the Confession of 1967.

In this important series of reflections, I have read my colleagues truth-telling imperatives about how racism and white privilege operate in our culture and church. With each narrative, we make ourselves vulnerable, exposing hurts and pains, telling stories that we know from experience are not always validated.

I add my story as a prayer, offered in hope, invitation, and challenge. My invitation is that we might live into our Presbyterianism and assume mutual responsibility and accountability for one another. My prayer is that more of my white sisters and brothers will assume some of this same vulnerability. My hope is that we can confess the sin of racism as it exists and operates in our church. And my challenge is that the denomination I love might move beyond complicit silence and actively repent of the sin of racism.

*****

AUTHOR BIO: Rev. Kerri N. Allen is a Reformed theologian, PhD student, and hospital chaplain in Chicago. Prior to responding to a call in ministry, Kerri had a first career in politics, serving as a political appointee at multiple levels of government, including serving as a legislative assistant in the United States Senate with an expertise in healthcare policy. Now, as a student in theology and ethics at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, Kerri uses her diverse experiences to focus on disparities in quality of healthcare for black women in the United States. Originally from St. Paul, MN when Kerri is not buried in a book or writing a paper, she enjoys hiking, travel, watching sports, cooking, or spending time with one of her many nieces or nephews.

Read more articles in this issue Call to Confession: Race, White Privilege and the Church!

Unbound Social