This interview takes us from US memories of the anti-apartheid movement to the continuing struggles for a more peaceful and prosperous South Africa. It looks at the power of hope but also the terrible legacy of underdevelopment. Stepping around the many laudatory remarks of politicians and commentators who generally did little to help end apartheid, Unbound turns to a man who has served the cause of justice in South Africa through the anti-apartheid movement since 1978, when he was a freshman at Macalester College. While some anti-apartheid activists began to move on to other issues after Nelson Mandela was released in 1990, Doug Tilton instead moved over to South Africa. He had made several research trips to South Africa in the mid- to late-1980s while working on his Masters and Doctoral theses at Oxford, but in 1992 he went to live in South Africa. He has served the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) first as a mission diaconal worker engaged in peacemaking in KwaZulu-Natal and later as an ecumenical liaison with the South African Council of Churches (SACC). In his current position, he coordinates mission partnerships of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) in Southern Africa and Madagascar. Tilton is interviewed by Chris Iosso, who has known him since the 1979 UPC General Assembly.

Chris: Let us start with today: did you ever meet Nelson Mandela? What opinions did you form of him? Allan Boesak, writing last year when Mandela’s decline began to become serious, says he is best characterized by his “dignity.” What kind of legacy is he leaving?

Doug: No, unfortunately I never had the pleasure of actually meeting Madiba. When I was working at the SACC Parliamentary Office in Cape Town in the late 1990s, I would occasionally catch a glimpse of him in the Parliamentary precinct. I was fortunate to be able to attend a special sitting of Parliament on the tenth anniversary of democracy in 2004 that both Mandela and F.W. De Klerk addressed. Afterwards, I was one of the hundreds of admirers who lined the exit route as he came past, shaking hands. But that is the closest I ever got.

___________________________________________

If, as President Obama said in his address at Mandela’s memorial, Madiba’s example made you want to be a better person, the way he treated you made you believe that you could live up to that challenge. And what he did for individuals, I think he also did for a nation.

___________________________________________

Certainly, Prof. Boesak is right that President Mandela’s own persona was one of incredible dignity. He combined this with an extraordinary humility that made him seem approachable. He not only believed that all human beings were worthy of equal respect, he lived out that belief in the way he treated everyone with whom he came in contact. This, I think, is part of why he was so profoundly and universally loved. If, as President Obama said in his address at Mandela’s memorial, Madiba’s example made you want to be a better person, the way he treated you made you believe that you could live up to that challenge.

And what he did for individuals, I think he also did for a nation. Even in death, Madiba is the one force – other than a major sporting event – that can make South Africans look beyond their differences and feel some sort of common bond – some sense of interdependence, unity, and mutual responsibility for one another. And while the euphoria of a World Cup or an Olympic victory can be ephemeral, Mandela seems to have a more enduring pull on the hearts of a nation. Mandela’s own commitment to service has inspired South Africans – and now the world – to commemorate his July 18th birthday by devoting time and energy to acts of charity and empowerment.

Chris: Mandela has been honored particularly for his non-vengeful approach to the white minority upon his release. For five years in prison, though, he had been turning down offers of conditional release,, insisting on the release of others and himself without pledges of nonviolence, showing firmness and not forgiveness. How did he come to move away from his earlier support for (and limited engagement in) armed struggle? How influential were leading Christians such as Desmond Tutu and Allan Boesak in his move to renounce violence? Had they helped create a different country during the many years of his incarceration?

Chris: Mandela has been honored particularly for his non-vengeful approach to the white minority upon his release. For five years in prison, though, he had been turning down offers of conditional release,, insisting on the release of others and himself without pledges of nonviolence, showing firmness and not forgiveness. How did he come to move away from his earlier support for (and limited engagement in) armed struggle? How influential were leading Christians such as Desmond Tutu and Allan Boesak in his move to renounce violence? Had they helped create a different country during the many years of his incarceration?

Doug: One of the things I have always found most admirable about Nelson Mandela was his refusal to be seduced by attempts to single him out, to set him up as the spokesperson for an entire movement or group. Although he is sometimes portrayed as an almost messianic figure, he discouraged such excesses, in both word and deed. His style was consultative; although his wisdom and insightfulness made him an opinion-maker, he was not a “lone ranger.” He did not see himself as above the collective wisdom of democratic structures.

Similarly, I think his uncomfortable embrace of armed struggle was more of a pragmatic move than a heartfelt conviction. One must remember that he rose to prominence in the African National Congress (ANC) Youth League as a proponent of the Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws, a campaign of non-violent civil disobedience. It was only several years later — as an increasingly brutal state demonstrated its readiness to kill peaceful protestors and armed liberation movements proliferated elsewhere in the world – that he and many other ANC leaders began to see violence as a last resort. Even then, their strategy for many years was sabotage of economic targets, with strenuous efforts made to avoid human casualties.

___________________________________________

While we rightly praise Nelson Mandela for his commitment to reconciliation – a commitment that he shared with many other ANC leaders – we must not forget that he insisted on justice and truth as preconditions for reconciliation.

___________________________________________

For Mandela and many of his colleagues in the ANC, violence was a means to an end, not an end in itself. Its goal was not to exact revenge on violent oppressors. Nor do I think that most ANC leaders harbored visions of an outright military victory over the apartheid state. Rather, the objective was to force the leaders of South Africa’s minority regime to the negotiating table. Remember that Mandela steadfastly refused to renounce the use of violence as a prerequisite for his release. The ANC did not suspend the armed struggle until August 1990, six months after Mandela walked out of Victor Verster prison. And even then it was only a suspension, with the implied threat of a return to armed activities if the regime did not negotiate in good faith.

While we rightly praise Nelson Mandela for his commitment to reconciliation – a commitment that he shared with many other ANC leaders – we must not forget that he insisted on justice and truth as preconditions for reconciliation. The remarkable thing about Nelson Mandela and the ANC was that, having secured political victories at the negotiating table, they remained faithful to their commitment to reconciliation.

This understanding of reconciliation was not all that far from the views of Allan Boesak or Desmond Tutu or the 150 other signatories of the 1985 Kairos Document, which argued: “Nowhere in the Bible or in Christian tradition has it ever been suggested that we ought to try to reconcile good and evil, God and the devil” (Sec. 3.1). At the same time, however, it is true that the resurgence of a popular struggle inside the country, a broad grassroots movement that included the United Democratic Front, the SACC, and a wide array of community groups, demonstrated the effectiveness of non-violent resistance, even in the face of a well-armed but increasingly demoralized state.

This understanding of reconciliation was not all that far from the views of Allan Boesak or Desmond Tutu or the 150 other signatories of the 1985 Kairos Document, which argued: “Nowhere in the Bible or in Christian tradition has it ever been suggested that we ought to try to reconcile good and evil, God and the devil” (Sec. 3.1). At the same time, however, it is true that the resurgence of a popular struggle inside the country, a broad grassroots movement that included the United Democratic Front, the SACC, and a wide array of community groups, demonstrated the effectiveness of non-violent resistance, even in the face of a well-armed but increasingly demoralized state.

Chris: I might note that when we first met, you were leading “Mac Out of South Africa,” asking Macalester College to divest from companies involved in apartheid, even as Ronald Reagan and his administration were strongly backing the white minority government and considered the African National Congress to be terrorists. I was working for Mission Responsibility Through Investment (MRTI) and the Advisory Council on Church and Society (ACCS). We started filing shareholder proposals in the early 1970s, and you may have thought we as a church were moving too slowly. As it turned out the Presbyterian Church divested first of securities in major military contractors and nuclear warhead makers responding to the 1980 Peacemaking: the Believers’ Calling. But that divestment process with military contractors helped us develop policy and criteria for divestment that we applied to the South African situation, ultimately divesting or excluding approximately $130 million in securities between 1985 and 1989.

___________________________________________

When I started becoming involved in the ant-apartheid movement, I was grateful to find so many people in the Presbyterian Church who shared our concerns. And, as you know, divestment played an important role in putting pressure on the apartheid regime and demonstrating solidarity with the internal resistance in South Africa.

___________________________________________

Doug: Yes, that’s right. When I started becoming involved in the ant-apartheid movement, I was grateful to find so many people in the Presbyterian Church who shared our concerns. And, as you know, divestment played an important role in putting pressure on the apartheid regime and demonstrating solidarity with the internal resistance in South Africa.

Chris: What have been the most challenging or heartbreaking realities about the “new” South Africa? What would you want to change most?

Doug: Let me say at the outset that I think it is important to own how far we have come. There is a tendency in political discourse in South Africa – whether over service delivery, crime, or corruption – to play the game of emphasizing a particular problem by minimizing South Africa’s achievements. The most extreme critics sometimes pretend that things were better “before”. If “before” means in the apartheid era, I think that such claims are delusional.

Having said that, there is still much that remains to be done. Political democracy has outstripped economic democracy. South Africa continues to have one of the most lopsided distributions of wealth and income in the world, while traditional rivals for that dubious honor –- particularly Brazil – have made more rapid inroads into inequality. Too little progress has been made in redistributing land and undoing the impact of a century of legislation that confined 80% of the country’s population to 13% of its land. Unemployment remains obstinately high; officially about 25%, but closer to 40% in terms of the expanded definition (which includes long frustrated work-seekers). Corruption diverts goods and services away from poor communities. And the pervasiveness and casualness of gender-based violence remains a national scandal.

Chris: What is the role of the church today in South Africa? Did the divestment movement give the churches credibility?

Doug: Churches in South Africa and abroad gained credibility by standing with the oppressed in times of trial. The divestment movement was one way for those outside of South Africa, including churches, to demonstrate solidarity with the liberation struggle and to intensify pressure on the apartheid state to change course. It was very important, but would have achieved little if it had not been for the internal struggle.

___________________________________________

Churches in South Africa and abroad gained credibility by standing with the oppressed in times of trial. The divestment movement was one way for those outside of South Africa, including churches, to demonstrate solidarity with the liberation struggle and to intensify pressure on the apartheid state to change course.

___________________________________________

The church remains an important social force in overwhelmingly Christian South Africa, though the capacities of ecumenical organs, such as the SACC, have dwindled alarmingly since 1994. Part of the problem is that the challenges facing South Africa have become so much more varied and complex. While apartheid was an obvious moral target that prompted focused and coordinated action, today there are many targets to chose from: poverty, inequality, unemployment, HIV and AIDS, gender-based violence, corruption, etc., etc., etc. At the same time, the international solidarity networks that helped to support the work of the SACC and member churches have fewer resources and competing demands. And the older, “mission” churches that comprise most of the SACC’s membership are losing members to newer independent churches, including “prosperity gospel” churches that often have a very different social and economic agenda.

Nonetheless, the church has continued to have a prophetic voice at critical junctures. For many years, the ecumenical movement cooperated with the labour movement and civil society to publish an annual critique of South Africa’s national budget. The “People’s Budget” identified ways that public resources could be deployed to have a greater impact on reducing poverty, inequality, and unemployment. Recently, church leaders have spoken out against attacks on homeless people in the Durban area and striking mine workers at Marikana.

Chris: While widely respected, the Truth and Reconciliation process has also been criticized for making apartheid a matter of individual faults rather than a systemic problem in which all whites participated. What do you think of that process?

Doug: I believe that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission made a valuable contribution to nation-building in South Africa. It enabled South Africans to construct a common history so that they could envision a shared future. It helped many South Africans to find out what happened to loved ones so that they could grieve properly and reach some degree of closure. It produced some stories of forgiveness and reconciliation that inspired the nation and the world. I think that its impact was overwhelmingly beneficial.

___________________________________________

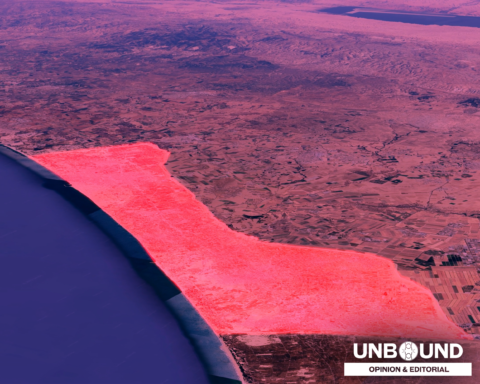

It is difficult for me to look at the map of Palestine today without seeing the 1980s maps of South Africa’s “Bantustans” – the scattered fragments of territory that the apartheid state tried to sell as coherent independent states.

___________________________________________

Did it achieve all that it set out to do? No. Many victims of gross human rights abuses were unable to participate in the process. For many, the symbolic reparations granted by the Commission were woefully inadequate. And, as you suggest, the Commission’s work ended up focusing largely on individual reparations with little attention to the community reparations that were also intended to be part of the process. So I would say that the exercise was flawed, but that it was also a nearly impossible task. Archbishop Tutu and his colleagues on the Commission did a remarkable job of keeping the focus on truth and reconciliation without allowing the process to be captured by narrow political interests or to become a forum for recriminations.

Chris: These days, the analogy of apartheid to Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians is invoked frequently. Can you comment on this?

Doug: It is difficult for me to look at the map of Palestine today without seeing the 1980s maps of South Africa’s “Bantustans” – the scattered fragments of territory that the apartheid state tried to sell as coherent independent states. I’m not sure how much should be read into that superficial similarity. But I know that the South African Council of Churches had a strong Ecumenical Accompaniment Program in Palestine and Israel, and the South Africans’ involvement was welcomed by many in the region who felt that their experience of apartheid gave them a good base for understanding and interpreting the Palestinian struggle.

Chris: What are signs of hope in South Africa?

Doug: There are many signs of hope in South Africa. Whenever I see diverse groups of young people socializing, I always marvel at how different their interactions are today than they would have been 30 years ago, when I first started going to South Africa. To a significant extent, “born frees” (young people born after 1994) tend to treat one another as equals, without falling immediately into the “superior-inferior” racial dynamics that were so common under apartheid. This is not to say that there are not still incidents of appalling racism, callousness, and abuse. But increasingly these are the exception and not the norm.

In addition, I would say that while South Africa has yet to really tackle the problem of economic inequality, social welfare legislation since 1994 has helped to build a “floor” under the poorest of the poor, preventing many from falling into absolute destitution. Recent reports indicate that the number of people living in the poorest socio-economic category has diminished significantly in the past two decades. The disastrously muddled response to the HIV pandemic has improved dramatically since 2009. Although there are still alarming glitches in distribution systems, life-saving antiretroviral medications are now much more readily available to people living with the virus. Consequently, new infection rates are diminishing and many people are able to live much longer, healthier lives.

Chris: Do you think you will you ever leave South Africa?

Doug: I’ve learned not to say that I will “never” do things. I don’t have any plans to leave South Africa. What I can say with certainty is that South Africa will never leave me.

*****

For other justice-oriented Christian perspectives on Mandela, see these articles from Allan Boesak, Peter Storey, and Vernon Broyles.

Unbound Social