Unbound Editorial, by Chris Iosso

Unbound Editorial, by Chris Iosso

April 17, 2013

As a runner of half-marathons and other races, I can half-imagine the setting just before the bombs went off. What runner will not think about that race and the attack intended to maim athletes? One commentator noted that the choice of target might not mean much to people in other parts of the world where foot racing and endurance athletics are not big. For him, that suggested a homegrown terrorist. For many of us who run to stay somewhat strong, it reminds us that muscles are not armor.

The famous Olympic race movie, Chariots of Fire, has the great runner Eric Liddell answer the question, “Where does the power come from, to see the race to its end?” His reponse: “It comes from within. The Kingdom of God is within you….”

Well, if the terrorist(s) turn out to be homegrown, then to the question, “Where does the violence come from?,” we will reluctantly answer; it comes from within.

We live in a violent and reactive world, one full of selective attention. For us as US citizens, for example, the Iraq War is over. But people are still being blown up, too often on their way to worship or even in mosques. People are fighting for survival in a state where the rule of law is weak and fate capricious. Every act of terror opens the door to that kind of a world. And the hard truth, should the bomber(s) turn out to be foreigners, is that our government is associated with “state terror” in too many places; through drones over Afghanistan, Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia (some based in the land of our repressive ally, Saudi Arabia), Guantanamo Bay, and support for the very symbolic but real occupation of Palestine. Many people in these countries believe that we export violence as a means to control parts of the world.

___________________________________________

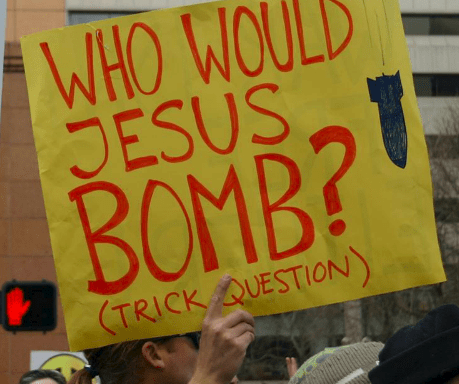

Terrorism is, essentially, a crime of theater, an act played before an audience, designed to call attention to a situation through shock, producing reactions of outrage and horror by doing the unthinkable without apology or remorse.

___________________________________________

Observers like Juan Cole have pointed to responses of empathy rather than “leaps to judgment.” Cole is helpful because his blog always provides an analysis of thinking from the Arab and Persian-speaking countries, often going under and around official declarations.

One Egyptian woman, for example, noted how important it is to have public officials expressing concern, including President Obama. The President is very good at public expressions of concern and uplift. Unfortunately, drone strikes he presumably approved for Afghanistan killed 30 people recently, and the New York Times featured a picture of four of the small shroud-wrapped bodies of children. We did not hear much public empathy on their behalf, and the drone program is an open secret. The continuing war in Afghanistan keeps over 60,000 US troops, perhaps 40,000 NATO troops, and 100,000 contractors employed, propping up a notoriously corrupt Karzai regime. Do many people think that things will be safer in Afghanistan when the bulk of NATO troops leave, and US presence is restricted to several large bases? The challenge for us will be empathy: will we care if no American soldiers or diplomats are dying?

The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)’s policy, “Violence, Religion, and Terrorism” (2004) remains a wise statement. Professor Ed Long has written a short and helpful book, Facing Terrorism: Responding as Christians, informed by his long studies of peace and war.

Bombs are wholesale terror, whereas bullets, even in a Newtown, seem to be absorbed as a retail problem. Gun violence is, in fact, a public health disaster and certainly a bigger threat than terror is likely to be in the United States. The enabling processes are quite different as well. Gun violence depends on powerful interests to limit commonsense solutions and thereby allows predictable murder levels far in excess of any other developed nation. Terror bombings—in most cases—can be seen as “blowback” from persons who perceive deep and deliberate injustice and can de-humanize (if not demonize) targeted groups. The 2004 report distinguishes between “transformative” and “suppressive” responses to terrorism, and, while favoring the first, sees a role for the second in maintaining order. But order alone, without justice, is repression.

Transformative strategies “address the political, economic, social, and cultural causes that underlie the resort to acts of terrorism.” The Violence, Religion, and Terrorism report contains some good analysis of triggers for terrorism in economic globalization and fundamentalist Islam, without ignoring elements in Judaism, Christianity, and other religions. A key concern of the report was to restrain the impulse to over-react to terrorism and fuel a “cycle of violence,” as was being done in Iraq as well as Afghanistan. The Christian faith gives us a better story than retributive justice.

The background paper to the Violence, Religion, and Terrorism report contains both an FBI description of terrorism and a description that captures more of a demonic dimension in terrorism:

“Terrorism is, essentially, a crime of theater, an act played before an audience, designed to call attention to a situation through shock, producing reactions of outrage and horror by doing the unthinkable without apology or remorse.” (p. 50).

To respond to this kind of theatre, the report looks to the power of nonviolence, which can also create moments of theatre. In this respect, the 2004 report also anticipates parts of the peace discernment process currently going on. The Peace Discernment resource, Encountering the Gospel of Peace anew, talks about violence in structural forms and forms of war and terror. That discernment process also introduces strategic nonviolence as found in parts of the Arab Awakening, which threaten tyrants and terrorists alike.

The process of responding to violence, however, is not about quick fixes: even public apologies and symbolic acts of reconciliation can take years to develop. Peace is a marathon for which we must save some energy for the 22nd mile and beyond. Destruction is quick, while creativity can be slow. Here is a response by Stephen Smith, a retired Boston-area minister who is also a painter, and his comment on the meaning of his painting:

___________________________________________

The process of responding to violence, however, is not about quick fixes: even public apologies and symbolic acts of reconciliation can take years to develop.

___________________________________________

Here is Smith’s account and invitation:

“Several years ago, when I first began painting, my cousin Brad shared with me this quotation by John Berger, that has stayed with me ever since: “Today, to try to paint the existent is an act of resistance, instigating hope.” In these last hours, as I have tried to make sense of the senseless violence in Boston, I have held fast to this act of resistance, by painting…

Yesterday, I began the painting I’ve attached. When I arrived in Spain (last year) at the end of February … to walk the Camino, the storks were already there. Migrating north from Africa, they heralded the coming of Spring by building their nests on every spire and high tower, as far as the eye could see. The stork is an ancient talisman in the Old World, seen as protector, bringing life into the world in birth, and escorting it from the world in death. For me, it brings great consolation in this time of turmoil and sadness, and so, I share it with you now to encourage your own “acts of resistance to instigate hope”, however this manifests itself.”

So to whoever planted those bombs, foreign or native-born: we will not stop the marathon of peace, and with God’s inspiration, we will create new ways to express love and justice together.

Notes:

Photos courtesy of Reuters(Photo #2), The Telegraph(Banner Photo) and Stephen Smith (Stork) .

Unbound Social