View and print as PDF

View and print as PDF

The overwhelming theological claim of the Bible in all its parts is that YHWH—

creator of heaven and earth,

savior and sovereign of Israel,

fleshed in Jesus of Nazareth

—is true God, who loves and governs all the world and to whom response is owed in praise, trust, and obedience. That mouthful of theological affirmations admits of no exceptions; acceptance of and response to it becomes the endless task and endless joy of a life of faith.

The Tension Is Not New

Since the outset, of course, women and men of faith have been busy sorting out which parts of that claim are most crucial and which parts are most commodious to our inclinations, a sorting out that is, at its best, an act of interpretation and, at its worst, idolatrous self-deception (see such sorting out in Mark 7:1-23; 12:28-34). Some of that sorting out comes under the current rubric of “evangelism and social action.”

With only a slight transposition of those two categories, one may see this tension, so alive now in the church, already vigorously voiced in Old Testament traditions that are likely brought to “final form” in the midst of Israel’s sixth century B.C.E. exile. The book of Leviticus and its agenda of “holiness” could not quite be termed “evangelism,” but the agenda of that tradition is surely aimed at recruiting more persons to the practice of a disciplined internal life in God’s presence and to the total disregard of life beyond that close community.

The Torah provisions of Deuteronomy could not quite be termed “social action,” but the agenda of that tradition concerned civic practices of economic neighborliness. Thus Leviticus (the Priestly tradition) and Deuteronomy (the Deuteronomic tradition) exhibit early on a tension—deeply embedded in the structure of the biblical canon—concerning what is most important in the life and practice of faith.

___________________________________________

The great temptation to the church—a temptation largely embraced—was to cede public life to an amoral concern for power and wealth and, conversely, to confine gospel concern to private-familial spheres where “religious” claims could be kept more or less credible.

___________________________________________

The contemporary split of evangelism and social action is made acute by the eighteenth century Enlightenment option of dualism that divided public life from personal spheres of reality. In a world of confident rationalism, gospel claims in the public sphere became very difficult to maintain. As a consequence, the great temptation to the church—a temptation largely embraced—was to cede public life to an amoral concern for power and wealth and, conversely, to confine gospel concern to private-familial spheres where “religious” claims could be kept more or less credible. That split persists today, so much so that direct assertion of God’s governance of the public realm sounds to our domesticated ears almost ludicrous. It is more “reasonable” to imagine that the public sphere is autonomous and not accountable to the rule of God.

What was a deeply thought intellectual, philosophical distinction in the eighteenth century has now been transposed, in the early twenty-first century, into a deeply felt socioeconomic, political, ideological question. That only means that our several vested interests are more immediately at play in interpretation but, nonetheless, around the same issues that have forever haunted this faith tradition and reached intellectual respectability in the eighteenth century.

The Tradition of II Isaiah

The question of relation between evangelism and social action and the relative importance of each for faith is being rethought in current conversation. The rethinking is urgent because the tension is unsustainable in any serious theology, and because it threatens the coherence of the community of faith. The dichotomy, moreover, is now less credible, given the erosion of confidence in Enlightenment modes of autonomy. If we view the Priestly and Deuteronomic traditions of the Old Testament as partisans in the dispute, we may make appeal to the tradition of II Isaiah (chapters 40-55),[i] an imaginative voice of Israel in exile and a near-contemporary of the Priestly and Deuteronomic traditions. It is the essential burden of II Isaiah to announce to exiled Jews in Babylon that the God of Israel is now acting (through Cyrus the Persian; see Isa. 44:28; 45:1) to seize the initiative in the Babylonian empire in order to permit displaced Jews to return home to Jerusalem. In order to announce that emancipatory message, it was necessary (and possible) to assert that YHWH, the God of Israel, has now reasserted sovereignty over all of public life, including the public life of the Babylonian empire.

What interests us is that II Isaiah (commonly dated 540 B.C.E.) is the first text in the Old Testament to use the term “gospel” (basar) intentionally as a theological term (Isa. 40:9; 41:27; 52:7). The “good news” proclaimed in this lyrical poetry is that YHWH—and not the despised gods of Babylon—is the true power in the world who now wills and authorizes a homecoming for Jews. That is, the “gospel” is a surprising announcement of God’s governance, surprising because the Babylonian powers seemed still in control. The gospel is a liberating authorization to depart the world defined by empire, and to begin to act in freedom under the new governance made available in this declaration.

This gospel assertion about the world coming under new governance is used in II Isaiah in order to articulate what we have come to call both “evangelism” and “social action.” The evangelism of II Isaiah is to recruit what must have been culturally defined Jews in Babylon (not unlike culturally defined Christians in the U.S.) into the theological conviction of YHWH’s sovereignty. The decision for a cultural Jew to become a theologically trusting Jew must have been jarring and displacing for many who had submitted to Babylonian authority in the same way that many cultural Christians have submitted to secular anti-life forced in the United States.

___________________________________________

The Isaiah tradition refused to choose between the “evangelism” of the holiness tradition and the “social acts” of the Torah tradition, but insisted that the new rule of YHWH pertains to all spheres, public and personal, worship and economics.

___________________________________________

To “evangelize” to the new reality of emancipation and homecoming was a major task, as is evident in the imperatives addressed to exiles, imperatives that assert at the same time a good news possibility and a demanding summons to receive that possibility (see Isa. 51:7; 52:1, 11). The imperatives bespeak urgency about a radical either/or and surely hint at reluctance, if not resistance, on the part of exiled Jews to accept the news. Thus II Isaiah is a primal “evangelist” who aims to recruit individual persons into the “new regime” in a way that will decisively impact their lives. The summons of this evangelist is surely not unlike our contemporary evangelism that seeks to bring individual persons under new governance that will decisively reshape their lives.

At the same time, there is no doubt that II Isaiah—to say it in any anachronistic way—is a social activist. His burden is “good news” that recruits Jews into a homecoming outside the grip of Babylonian imagination. More than that, his poetry is a message of “justice” that insists that YHWH’s rule of Babylon and “the isles” impacts them as much as it does displaced Jews. Thus in Isaiah 42:1-4, the “servant” (presumably Israel) is to “bring forth justice” to the nations, will faithfully “bring forth justice,” and will “establish justice” in the earth. The term “justice,” used three times in this text, is not explicated here. The usage in the larger tradition, however, makes it certain that the term here bespeaks reordered social relationships between the strong and the weak, the rich and the poor. It is ludicrous to imagine that this God would recruit individual persons to new governance and would not at the same time reorder social relationships in the public sphere.

In Isaiah 51:4-5, moreover, it is YHWH’s justice that will be a “light to the peoples,” also termed “salvation, deliverance” in this text. The phrase “light to the nations” surely pertains to public governance as the term is also used in Isaiah 42:6 and 49:6. In the horizon of this poet, every individual person counts, and every social, systemic relationship is subject to drastic reordering.

The New Rule of YHWH

It is clear that the large evangelical vision of II Isaiah continued to energize (and vex) the exilic community upon its return home to Jerusalem. (I use the term “evangelical” in the way I judge to be proper, as an adjectival form of “gospel.”) In Isaiah 56:1, immediately after II Isaiah and the first verse of III Isaiah (chapters 56-66), the first issue articulated is the practice of justice. In Isaiah 56:3-8, moreover, the poetry voices what I would term an “evangelical” question about who gets into the community, who is to be recruited. The poem astonishingly urges that “evangelism”—admission to the community of worship—includes foreigners and people with socially unsanctioned sexual history (eunuchs), so that evangelism is related immediately to questions of justice. In Isaiah 58:1-9, in parallel fashion, worship, in the midst of a sharp dispute, is dramatically redefined in terms of social action:

Is not this the fast that I choose:

to loose the bonds of injustice,

to undo the thongs of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke?

Is it not to share your bread with the hungry,

and bring the homeless poor into your house;

when you see the naked, to cover them,

and not hide yourself from your own kin? (Isa. 56:6-7)

To be sure, there were those who did not agree, or this disputatious text would not voice such an urging. It is clear that the Isaiah tradition refused to choose between the “evangelism” of the holiness tradition and the “social acts” of the Torah tradition, but insisted that the new rule of YHWH pertains to all spheres, public and personal, worship and economics.

An Urgent Question for the Church

The question of evangelism and social action is now before the church in an urgent way. This is, I suggest, a moment when the church is summoned to unlearn a lot of bad habits and critique some long-held assumptions. Much of the current conflict in the church is inherited and surely not germane to the place in which God has now set the church.

The party of “evangelism” might critique and unlearn the privatism of its vision, for most who do old-time evangelism (even in new electronic modes) resist thinking systematically about God’s rule of sociopolitical, economic systems. Such “individualism” is a social inheritance that comes from Enlightenment thinking about the private sphere and not at all from the Bible.

The party of “social action” might critique and unlearn the autonomy of its vision, for most old-line “social activists,” even in more urbane forms, still assume that “God has no hands but ours” and that the “mission” of social action is our mission and not the mission of God. Such “acting” is a social inheritance that comes from the Enlightenment and not from the Bible.

___________________________________________

In this new vision, the “evangelizing party” might learn that God’s new rule is more demanding and more dangerous than “winning souls.” The “social action party” might learn that the mission is not “ours,” and so be delivered from a shrill (often self-serving) ideological tone.

___________________________________________

The unlearning that must happen cannot be done by either party alone. It must be ecumenical in the service of a common critique of privatizing evangelism and autonomous social action, a shared rethinking about the character of God, God’s will for the world, and God’s way in the world. The striking power of the poetry of II Isaiah is that he refused to concede anything to the “powers” of this age. He understood that YHWH’s newly asserted governance immediately subverted every imperialism; at the same time, he conceded nothing to either the “holiness party” or the “Torah party,” drawing on both to fashion a new vision.

In that new vision, the “evangelizing party” might learn that God’s new rule is more demanding and more dangerous than “winning souls.” The “social action party” might learn that the mission is not “ours,” and so be delivered from a shrill (often self-serving) ideological tone. It would be unfortunate—not to say unfaithful—if these several “sects” in the church continued to recycle old categories and old conflicts, so mesmerized by the ancient quarrel that we commonly miss “the new thing” God is doing in the world (see Isa. 43:18-19).

I suggest that neither party can discern God’s current newness alone. It will require an ecumenical attentiveness that holds together in common trust parties from an old, obsolete quarrel. The people of God need no longer permit old quarrels to dominate current obedience. That is good news among us, perhaps our equivalent to the freshness of II Isaiah, who used the “gospel” to recruit adherents to the new governance and dispatched them to waiting “isles” to enact justice. That vision is older and deeper among us than our more recently learned and treasured disputes readily acknowledge.

Notes

[i] The Old Testament book of Isaiah is generally accepted to be a collection of writings from three eras in Jewish history, The prophet Isaiah, acknowledged to be the author of chapters 1-39, lived during the time when the Northern Kingdom was taken by the Assyrians. II Isaiah, chapters 40-55, comes from a later time, the fall of the Southern Kingdom, the Exile in Babylon, and Cyrus of Persia. The remaining chapters, 56-66, come from a time later yet when God’s people were dealing with life in the new, restored community in Palestine.

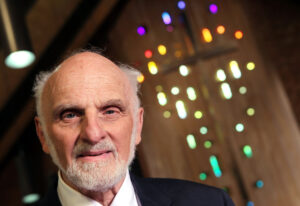

Walter Brueggemann is William Marcellus McPheeters Professor Emeritus of Old Testament at Columbia Theological Seminary. He is a past president of the Society of Biblical Literature and an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ. He has recently written Disruptive Grace (Fortress Press) and David and His Theologian (Wipf and Stock).

Banner Image by “Trounce.”

Walter Brueggemann is William Marcellus McPheeters Professor Emeritus of Old Testament at Columbia Theological Seminary. He is a past president of the Society of Biblical Literature and an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ. He has recently written Disruptive Grace (Fortress Press) and David and His Theologian (Wipf and Stock).

Banner Image by “Trounce.”

Unbound Social