I’m sure you’re familiar with the story. A rich young man approaches Jesus and asks what he must do to gain eternal life. Jesus comes off a bit nonplussed at first, since it should be quite obvious what one must do: “If you wish to enter into life, keep the commandments” (Matt. 19.17). The man assures Jesus that he has kept the commandments, but he still has a sense that he is lacking something. Jesus then says, “If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your possessions, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then, come follow me” (Matt. 19.21). The young man, the gospel tells us, “went away grieving, for he had many possessions” (Matt. 19.22).

Jesus isn’t really known for sugarcoating what is required to follow him, but the commandment he gives here certainly ranks among the more difficult. Perhaps that’s why, more often than not, this teaching is downplayed and blunted. We do all we can to make it easier to swallow, to make it “cheap,” as Dietrich Bonhoeffer might have said.

I’ve taught this text numerous times in various different classes, and the reaction is always the same: Jesus didn’t really mean what he said, at least not in a way that applies to everyone. Sure, Jesus counseled the rich young man to sell his possessions and give it all to the poor, but that’s because Jesus “knew the heart” of the young man: the young man valued his possessions and wealth above all else. Jesus knows our hearts also, and he counsels each of us to give up that thing that blocks us from gaining eternal life. It might be money for some, but it could be any number of things, really. The problem is whatever gets in the way of “our relationship with God.”

___________________________________________

As the story of the rich young man makes clear, the disciples understood that there is something about wealth, something about having possessions, that makes it difficult to follow Jesus.

___________________________________________

In other words, the interpretation goes, Jesus isn’t really speaking about wealth at all. It’s a common reading – I’m not singling out my students as unique. Indeed, I suspect that most individual Christians and churches, especially those in wealthier, industrialized nations, read what Jesus says to the rich young man metaphorically. But it’s a problematic reading. If we read a little bit further in the text, it’s clear that Jesus was really saying something specifically about wealth.

As the rich young man goes away “grieving” over the whole situation due to his “many possessions,” Jesus continues the conversation with his disciples, “Truly I tell you, it will be hard for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven. Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who has wealth to enter the kingdom of God” (Matt. 19.23-4). It’s hard to imagine that Jesus is just saying something about “our hearts” and what we individually value, here: he clearly singles out wealth as a hindrance to entering “the kingdom of heaven.” That’s certainly how the disciples understood what he said. They’re all too quick to remind Jesus that, unlike the rich young man, they have left all: “Look, we have left everything and followed you. What then will we have?” (Matt. 19.27).

These disciples were not rich individuals, mind you. These were not persons who, like the rich young man, would find their “many possessions” the biggest barrier in their relationship with God. Although it’s difficult to make certain claims about their respective financial situations, there’s nothing in the gospels to suggest that the disciples were persons of means. And yet, they still found it necessary to forsake what they had—little as it may have been—to follow Jesus. For, as the story of the rich young man makes clear, the disciples understood that there is something about wealth, something about having possessions, that makes it difficult to follow Jesus.

The choice between wealth and following Jesus is not, of course, isolated to the story of the rich young man. It’s one of the more consistent themes found throughout the gospels, inflected variously in word and deed. We need only look at what Jesus says about the impossibility of serving God and Mammon simultaneously. It is impossible, Jesus says, to “serve two masters; for a slave will either hate the one and love the other, or be devoted to one and despise the other” (Luke 16.13). Since, as Jesus says elsewhere, a house divided against itself cannot stand (Matt. 12.25), it is impossible to serve at the same time God and wealth. As Philip Goodchild has expressed the matter in his Theology of Money, God and wealth compete for time, attention, and devotion – and there’s only so much of each to go around.

Again, the opposition between God and wealth here is not metaphorical, as if anything that we value over against God could slide seamlessly into the place of wealth. For Jesus, wealth is a real competitor to God—and because of this, it bears uniquely within itself the potential to draw our attention away from God and toward itself. We should never forget that Judas, a once loyal disciple, sold Jesus out for “thirty pieces of silver” (Matt. 26.15).

This opposition between God and wealth – and how it determines our relations to others – is what is at stake in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16.19-31). The rich man knew what was required of him, knew his responsibilities to the poor such as Lazarus. Yet his wealth led him to callously ignore Lazarus’s plight, even though Lazarus lay day in and day out at the rich man’s gate. Upon their respective deaths, Lazarus is rewarded, while the rich man is punished in fiery torment, with a great, uncrossable chasm fixed between them. The chasm that separated them in this life is thus reversed in the hereafter: as Jesus says elsewhere, “the last will be first, and the first will be last” (Matt. 20.16).

___________________________________________

It’s important to point out that the callousness of the rich man does not appear to have arisen from any malicious intent. Indeed, the rich man does nothing at all to Lazarus, and that’s the problem: the enjoyment of his own wealth blinds him to the fact that Lazarus even exists, even as Lazarus sits right outside his gate.

___________________________________________

These are harsh words, and to the extent that we take them seriously, we like to think we fall on the right side of the opposition between God and wealth. We are not like the rich man in the parable, we tell ourselves. We, of course, would never be so callous.

It’s important to point out, however, that the callousness of the rich man does not appear to have arisen from any malicious intent. Sure, he ignores Lazarus, but his refusal to pay heed to Lazarus’s needs is the direct result of his wealth and his enjoyment of it rather than any specific, nefarious act. Indeed, the rich man does nothing at all to Lazarus, and that’s the problem: the enjoyment of his own wealth blinds him to the fact that Lazarus even exists, even as Lazarus sits right outside his gate.

We are more like the rich man than we like to think. We may say that it is important to remember the poor, and may even give a small amount of our time, resources, and wealth to them – charity. Yet our actions often speak otherwise: like the rich man, our enjoyment of our wealth blinds us to those who long to satisfy their hunger (Luke 16.21). Thus do we ignore the immigrant who leaves family to labor tirelessly to fill our plates with a variety of foods; the child who sews our clothes and shoes so that we have the latest, inexpensive styles; the peasant who constantly breathes in toxic fumes to assemble our latest technology; and the homeless person who simply wants a cup of coffee, something to eat, and to be treated as a human being. For most of us, such ignorance is neither calculated nor malicious; nevertheless, it is a direct result of our wealth and our enjoyment of it, which seems to be what Jesus was getting at.

When confronted with the problems that wealth causes, for others and for us, we too walk away grieving over our many possessions, for just like the rich young man, we can’t imagine our situation otherwise. And to avoid this hard truth, we try to make these jarring texts about anything other than wealth. It’s about our hearts, we say, even as we ignore the fact that, deep down, our hearts are captive to our wealth.

Ironically, by ignoring that the problem really is our wealth, we miss the grace in the story. As the rich young man goes away grieving, Jesus tells his disciples how hard it is for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven (Matt. 19.24). That doesn’t really sound like good news, and his disciples respond with understandable astonishment, “Then who can be saved?” (Matt. 19.25). Jesus looks at them, and says, “For mortals it is impossible, but for God all things are possible” (19.26).

We shouldn’t read what Jesus says, here, as an excuse for our wealth, as a get out of jail free card, so to speak. Grace is certainly offered, but accepting that grace also entails owning up to the ways that our wealth blinds us to the plight of others, the ways that it blinds us to God. Our choice is still between God and Mammon, but we can take comfort in the fact that we don’t have to make that choice alone. The choice may, as it did for the rich young man, involve some grieving, but we need not walk away as he did. For it is in not walking away that we truly find grace.

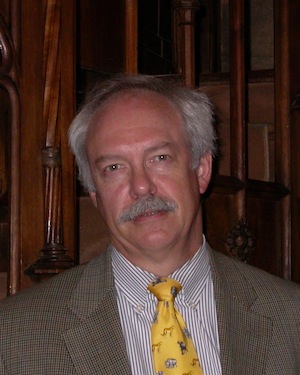

AUTHOR BIO: Hollis Phelps is Assistant Professor of Religion at Mount Olive College, Mount Olive, NC. He is the author of Alain Badiou: Between Theology and Anti-Theology (Acumen Publishing, 2013).

AUTHOR BIO: Hollis Phelps is Assistant Professor of Religion at Mount Olive College, Mount Olive, NC. He is the author of Alain Badiou: Between Theology and Anti-Theology (Acumen Publishing, 2013).

Unbound Social