A Review of Ender’s Game

Director and screenwriter Gavin Hood‘s stunning Ender’s Game comments on many of the crucial ethical issues of our time, much like its source material, the eponymous 1985 novel. The author, Orson Scott Card, who served an advisory role in the production of the film, has become notorious for his own take on several social issues as well, marriage equality chief among them, so it is nearly impossible to comment on the film without addressing his controversial statements:

Director and screenwriter Gavin Hood‘s stunning Ender’s Game comments on many of the crucial ethical issues of our time, much like its source material, the eponymous 1985 novel. The author, Orson Scott Card, who served an advisory role in the production of the film, has become notorious for his own take on several social issues as well, marriage equality chief among them, so it is nearly impossible to comment on the film without addressing his controversial statements:

With “gay marriage,” the last shreds of meaning will be stripped away from marriage, with homosexuals finishing what faithless, selfish heterosexuals have begun.

After reading the 2009 essay containing those words, I was appalled. I have spent hours of my life poring through Card’s Ender novels, plucking out bits of wisdom about tolerance and relating to the “other.” I have read and re-read these novels that I held dear, that became an essential part of my worldview, and suddenly, that worldview was shattered. These stories of reconciliation felt oddly tainted and hypocritical, and so I approached Hood’s Hollywood retelling of a favorite childhood story with hesitancy and lots of research. I was grateful to see the director make a powerful public statement regarding his own disagreement with Card’s opposition to marriage equality:

Orson Scott Card wrote a book about compassion, and empathy, and yet he himself is struggling to see that his position in real life is really at odds with his art.

Compassion and empathy are certainly important themes, possibly the most prevalent through all retellings of Ender’s story, but Hood’s film does little to hide the novel’s cutting commentary on the state of human society (marriage equality not mentioned). Hood stays almost eerily close to his source material while translating the social concerns of 1985 into something entirely relevant for 2013. It should also be of note that the author sold his rights to the Ender’s Game property over 10 years ago and allegedly has no back-end profit deals in place for the film, so when my wife (who was wholly unfamiliar with the book) and I arrived at the theatre on opening weekend, I was in good spirits and ready for another Hollywood re-creation of a much loved childhood story.

___________________________________________

Hood stays almost eerily close to his source material while translating the social concerns of 1985 into something entirely relevant for 2013.

___________________________________________

For the uninitiated, Ender’s Game follows the story of Andrew ‘Ender’ Wiggin, a brilliant child bred for success on a post-extraterrestrial-contact Earth in 2086. A century before the film’s events, under threat of invasion by the ant-like Formic alien species, the governments of the world (in a rare moment of solidarity) decided to train Earth’s best and brightest to lead the International Fleet should the Formics ever return to Earth. Selected as children and filtered through rigorous schools, the most promising candidates are launched off-planet to an orbiting facility known as the Battle School, a boot camp where they are, in Ender’s own words, “trained on war games, their decisions [in combat] intuitive, decisive, and fearless.” Ender (Asa Butterfield) is chosen at a very young age to attend the program, much to the dismay of his violent, nearly-sociopathic eldest sibling Peter and his compassionate, nearly-saccharine sister Valentine. A balance of his siblings’ extreme personalities, Ender is selected by Colonel Hyrum Graff (Harrison Ford) and Major Gwen Anderson (Viola Davis) as humanity’s greatest hope should the interspecies war ever re-visit the home planet.

The film begins in the middle of the events of Ender’s selection, showcasing his brilliance and capacity for strategy, but also the features that link him to siblings Peter and Valentine – particularly his propensity to resolve a conflict with just enough deliberate force to prevent any future conflicts. As Ender heads off to Battle School, we get our first glimpse at the unbelievable visual effects work provided by Digital Domain and Comen VFX – if anything, Hood’s film is very easy on the eyes, and the studios involved have done a fantastic job making the more unbelievable parts of Ender’s Game come to life in a very believable way.

As Ender straps into a shuttle and heads for the orbiting training grounds, the film teases us with the first of its many important themes – perception of people and the world around us. Ender proves to be the only ‘Launchie’ cadet capable of shifting his perceptions of gravity, an asset which leads to his greatest successes in the International Fleet but also showcases the first of the film’s not-so-hidden commentaries on the military. Colonel Graff and the Fleet intend to hone Ender into a weapon throughout his time in Battle School by their war games, psychological experiments, and forced isolation. The first great offense here is simple – Ender is a child, and – while brilliant – has plenty of development left to do, especially in his capacity for decision-making. In the film, Major Anderson cites the Geneva Convention, our current international standard, which prohibits the recruitment of anyone less than 15 years old – Asa Butterfield’s character appears 10 or 11 years old, and in the book, Ender is only 6 when he is chosen for Battle School. I can think of few people who would find employing child soldiers a ‘just’ practice, and yet, under the cloak of education, the International Fleet does just that.

The government-sanctioned use of child soldiers is certainly not the only unjust practice in this paranoid future society, though, and not the only one with uncanny parallels to the world in 2013. Consider the structure of the Battle School program – cadets are put through a rigorous selection process, driven until their minds and bodies are ragged, and then honed into the perfect weapons of war. In contemporary US military boot camps, recruits are run into the ground, drill sergeants treat their inferiors like raw material to be re-programmed, and so people are trained to be able to kill, and to embrace (or adjust to) military life. In the world of Ender’s Game, these children are the best and brightest – brilliant minds, capable of furthering the cause of humanity in hundreds of different ways, but those futures are snatched away from them by the International Fleet at the cost of their spirits, all for the promise of a place in the history books.

SPOILERS AHEAD

As we close on the finale of Hood’s 114-minute film, Ender is selected to join the ranks of the elite in Command School – a crucible for the star cadets located at the hidden forward command post of the international fleet. This final training ground is a Promised Land for most of the Fleet’s cadets, but for Ender, his promotion is bittersweet – he recognizes that he’s being used not only for his brilliance, but also for his capacity to understand the enemy. “I’ve won because I always understand how my enemy thinks. And when I truly understand them, I also love them,” he confesses during a conversation with his sister Valentine (Abigail Breslin, yes, that’s Olive from Little Miss Sunshine). Ender gets it; he understands what Graff and the Fleet are doing to him. He realizes it’s a game, so he decides to treat it like one.

___________________________________________

What are the implications for the use of drones as a method of war that allows a group of children to wipe out an entire race while they (along with the audience) believe they are playing a glorified video game?

___________________________________________

By the end of the demanding cycle of (incredibly impressive) simulated space battles the Admirals have prepared, Ender decides to break the game. He commands Petra Arkanian (Hailee Steinfeld), one of his lieutenants and friends from the Battle School, to fire an impossibly destructive weapon at the target of the simulation, the Formics’ home planet and last refuge. Believing he’s won against the commanders and military bigwigs gathered to watch his graduation ceremony, he takes on a tauntingly triumphant attitude not unlike Chris Pine’s James T. Kirk in Star Trek. In response, the leaders of the Fleet are unbelievably solemn – eventually revealing to Commander Wiggin and his lieutenants that they’ve won the war, struck a pre-emptive blow against the Formic militaries, and utterly destroyed their enemy through this method of “total war.” The bleak consolation they offer their child admirals is that it was the “right thing to do,” but Ender, who, in horrified despair at this betrayal of his trust, describes what he’s done as “genocide,” is not so sure.

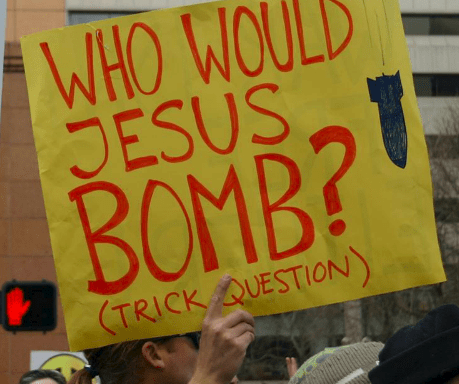

Ender’s Game is more than a story about overcoming bullying and the troubled lives of gifted children. Gavin Hood’s retelling highlights the novel’s critique of the “just war” arguments so often invoked in conversations about war and peace. Is the war against the Formics justified? What about the pre-emptive strike that wipes out their planet in the name of “preventing future conflicts?” Were nonmilitary means available? What are the implications for the use of drones as a method of war that allows a group of children to wipe out an entire race while they (along with the audience) believe they are playing a glorified video game? Will victory bring a just peace? Will the universe Ender lives in be better after the end of the conflict? The conclusion of the film, while leaving much to be desired for avid fans of the original novel, nevertheless leaves us with the hope that the exploited hero will find his answers and begin to make peace in the universe in which he’s been trained only to make war.

AUTHOR BIO: Andy Bairby is a Sci-Fi reader who is passionate about justice and peacemaking and served as a YAV in Northern Ireland doing just that. He was very hesitant to buy tickets to see this movie until he found out that Orson Scott Card wouldn’t get any more cash from his movie ticket, only the exploitative Hollywood movie industry that really likes explosions.

Read more movie reviews from Unbound.

Unbound Social