A Tradition to Counter Historical Amnesia.

For everyone following the common lectionary, this Sunday (March 17) includes what is called Jesus’ “lament” over Jerusalem, Luke 13: 31-35. His weeping occurs as the city comes into view in chapter 19, verses 41-44.

Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem is the framework for Lent, as we follow the Gospel writers as they prepare us for Holy Week and its share of weeping in Gethsemane and on Golgotha. Christians today should weep regularly for Jerusalem, for all its living inhabitants—for all its spiritual children that Jesus would gather in despite the layers of tragedy. The practical amnesia about the meaning of Jerusalem aids and abets the current tragic trajectory.

In Luke’s text, when some of the more friendly Pharisees warn Jesus that Herod is after him, he takes their point but points ahead to Jerusalem as the truly dangerous place. As he follows the pattern of the prophets, he knows the cruel appetites of capital cities, even subjugated ones: “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it!” Even though he is one of those sent, he laments for the people and rulers of the city, not himself. And Jerusalem is already becoming a Christian symbol for a spiritual goal, building upon that history of prophetic confrontation with kings. Luke (and Matthew even more) show the intense debates between Jesus and other Pharisees over the Law and faithful practice, highlighting differences of style and content in their teaching.

___________________________________________

Jerusalem symbolizes a part of our tradition, but is rightly overshadowed by Jesus himself—or does that partly disembody Jesus from the early Christian community?

___________________________________________

Jews weep regularly for Jerusalem, or more exactly for the two temples: one pulled down by the Babylonians in 586 BCE and the second by the Romans in 70 CE. A holiday called Tisha B’av consists partly of chanting the book of Lamentations–five grief poems about the destruction of the first temple—which is begun on the 9th day of the month of Av, when Titus’ Roman army was said to have destroyed the second. When this holiday coincided with the latest massive Israeli war on Gaza, in 2014, the Rabbinical Council of Jewish Voice for Peace wrote a moving text that moves across time between the two hammered cities. (Though Jeremiah also weeps over Jerusalem, he did not write Lamentations, which is put in a different section of the Hebrew Bible).

Most of those preaching this Sunday will not pay too much attention to Jerusalem, either at the time of Jesus or today. When I was a pastor, I would often do something with the juxtaposition, but did not go into much detail about Jerusalem. Reformed Protestants do not require pilgrimages, nor do we sacralize any part of the earth that might become an idol, mixing blood and soil. Jerusalem symbolizes a part of our tradition, but is rightly overshadowed by Jesus himself—or does that partly disembody Jesus from the early Christian community?

Another downside of that limited treatment is that we easily assume Jerusalem to be more of a Jewish city than it has been, underestimating the longer periods of Christian and Muslim presence, with their struggle and co-existence. When Prime Minister Netanyahu several years ago sought to re-write history with grand assertions of Jewish ownership and continuous presence, historian Juan Cole deflated his claims with a very blunt historical summary

Cole speaks to the origin of the name: “Jerusalem, Daru Shalem, was founded sometime between 6500 and 5500 years ago, by the proto-Canaanite people long before Judaism existed. It was dedicated to the god of dusk, Shalem.” He underlines the sheer duration of Muslim rule, both before and after the Crusaders, “or altogether over a millennium. So Iran [Persia/Babylon] ruled Jerusalem altogether for some 250 years, and the Crusaders for about 200 years, and it was the capital of lots of peoples, including Canaanite kingdoms and the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was also often a provincial capital under Muslim empires.” (Cole echoes an earlier column which does more of the historical math).

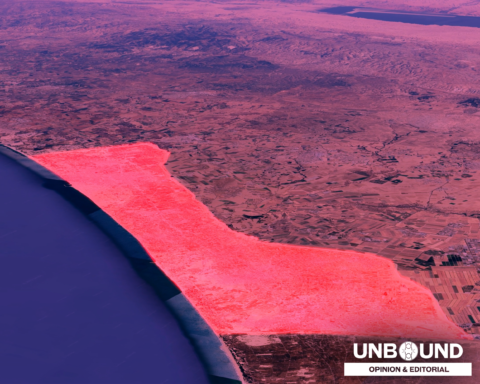

In practical terms, the current victors are re-writing the history in very physical ways, “Judaizing” Jerusalem, in the phrase of Daniel Seidemann. By excavating, protecting, and show-casing mainly Jewish structures, Christian and Muslim structures and lands, even graveyards, are downgraded, cut off by the separation (apartheid) wall, and in some cases made into “nature” parks by eminent domain. Much of the reality of the city is everyday jostling, albeit with armed Jewish settlers and soldiers and always unarmed Christians and Muslims, but Seidemann looks to the deeper, longer term:

“This is not real estate. It is the epicenter, the volcanic core of the conflict. Most of the issues between Israelis and Palestinians can be addressed by mortal men and women because it is a territorial, national, political conflict. But when you get into the area of the Old City and around it you are talking about sacred space and repositories of historical memory. This is where the tectonic plates of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam and the Arab world meet.”

A regular rite of weeping or grieving by the Christian community would remind us of the steady pressure the Palestinian Christians and Muslims are under and encourage greater solidarity. The overall grim picture is the end of the two-state aspiration, carefully catalogued following the original Oslo categories in the 2016 General Assembly report. Each new settlement, each new attack by settlers, each new length of the wall, each expulsion of a Jerusalem resident married to someone from the West Bank, each home demolition, each olive tree cut down, each polluting of Palestinian water supplies, each public investment inaccessible to Palestinians, each natural resource taken from “Area C,” the Jordan Valley essential to any viable Palestinian State: together these show an Israel determined to exploit Palestine to the fullest. The lockdown – total boycott—of Gaza is replicated in the little encircled “bantustans” across the West Bank. And for the Christian community, the severing of East Jerusalem from Bethlehem and traditionally Christian areas of the West Bank by the ring of fortified settlements is particularly hard.

The recent collection of essays and research, Why Palestine Matters: The Struggle to End Colonialism, illuminates the many ways support for Israel accustoms the US to regressive patterns of militarism, racism, and inequality. For US Christians, knowing that Christ does not always stand on the “winning” side is an important truth—as even our recent military losses are still presented as victories. The conservative government of Israel influences a certain amount of US foreign policy, as the recent controversies with the new Muslim members of Congress reveal. Was breaking off the Iran nuclear weapons deal a wise decision? Will the US administration make more explicit its de facto recognition of Israel’s annexation of Syria’s Golan Heights? Would that help Prime Minister Netanyahu’s re-election campaign? What about the US closing its consular offices for Palestinians in East Jerusalem while leaving the facilities used by Jewish Israelis intact?

‘ “Israel is not a state of all its citizens,” he [Benjamin Netanyahu recently] wrote in response to criticism from an Israeli actor, Rotem Sela. “According to the basic nationality law we passed, Israel is the nation state of the Jewish people – and only it.” ‘

How is that law not a recipe for apartheid?

But marking the deterioration of Palestinian living conditions and loss of rights is not enough. The full context of measurement and awareness should be the hopes for an international city of peace reflected in the UN’s original vision, which kept Jerusalem (and Bethlehem) a neutral place. Such an international city was preempted by the declaration of a State of Israel that goes well beyond the 56% of original Palestine in the initial partition, which was never seriously negotiated.

Is this piece one-sided, or even “tribal,” in supporting the diverse Palestinian traditions? It is written from the conviction, firstly, that the reality is as one-sided as the death tolls in Gaza. It is also written from the conviction that it is in Israel’s best interest to ensure equal justice and respect for non-Jewish groups—that justice has historical and cultural dimensions that empower all people.

Theologically, the church has neglected its own resources that relate to Jerusalem. In 1995, the General Assembly endorsed the “Memorandum of Their Beatitudes the Patriarchs and of the Heads of Christian Communities in Jerusalem,” November 14, 1994, on “The Significance of Jerusalem for Christians,” which declares that:

“Jerusalem is a symbol and a promise of the presence of God, of fraternity and peace for humankind, in particular the children of Abraham: Jews, Christians, and Muslims,” and which calls, further, “upon each party to go beyond all exclusivist visions or actions, and without discrimination, to consider the religious and national aspirations of others, in order to give back to Jerusalem its true character and to make of the city a holy place of reconciliation for humankind.”

The 1995 General Assembly also reaffirmed that “the future of Jerusalem is not simply a political, social, or economic issue, but is, at its heart, a religious issue grounded in the commitment of three faith groups who claim to be the children of Abraham and for whom, in the providence of God, Jerusalem is a unique symbol of the hope for a future marked by peace and justice for all God’s children.”

Is it still such a symbol for Presbyterians and other Christians? For Jews in Israel, in the US, and elsewhere? Have we given up on reconciliation and seek either domination or liberation? Can weeping, acknowledging suffering, grieving together possibly re-open a closing horizon? And, for Christians, will a museum-Jerusalem carry anything of the depth of meaning that the city has held in the past?

[1] “Benjamin Netanyahu says Israel is ‘not a state of all its citizens.’” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/10/benjamin-netanyahu-says-israel-is-not-a-state-of-all-its-citizens. Accessed 03/16/2019.

***

Author Bio: Senior Editor Chris Iosso has been ordained (Elizabeth Presbytery in NJ), inducted into General Assembly Mission Council service in NYC, and educated (Johns Hopkins—BA, Princeton—Mdiv, and Union (NY)—PhD, Seminaries) in the print dispensation. After serving as a pastor and parent of three in Westchester County, NY, he returned to the PMA as Coordinator of the Advisory Committee for Social Witness Policy. He is married to chaplain Robin Hogle. Beyond books, he enjoys running, kayaking and soccer.

Unbound Social