Two Contrasting Narratives of What Happened at the General Assembly Reveal a Critical Generation Gap

By Patrick David Heery, Unbound Managing Editor View and Print as PDF.

View and Print as PDF.

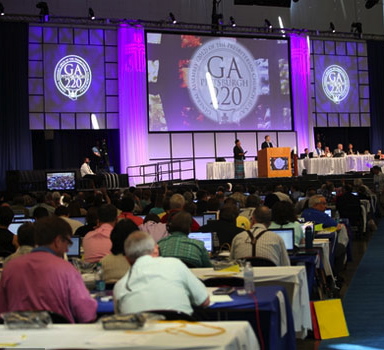

Talk to enough social justice-minded Presbyterians and you’ll likely hear two distinct interpretations of the 2012 PC(USA) General Assembly.

Talk to enough social justice-minded Presbyterians and you’ll likely hear two distinct interpretations of the 2012 PC(USA) General Assembly.

Narrative One:

A Successful, Albeit Cautious, Assembly

One interpretation (such as can be found in my colleague Chris Iosso’s editorial) says General Assembly represented a reasonably successful, albeit cautious, promotion of justice. The Assembly approved, by wide margin, the entire docket of the Social Justice Issues Committee. Out of this Assembly came commitments to challenge the unlimited campaign donations of corporations and wealthy donors; to endorse a “Fifty Year Farm Bill” to improve the sustainability of American agriculture and food supply, while advocating the fair and dignified treatment of laborers; to investigate the corporate practices of for-profit prisons and health insurance companies; to advocate for comprehensive immigration reform ranging from legislation like the DREAM Act to a complete overhaul of our detention system; to participate in a churchwide discernment of whether it is time to become a “peace church”; and to boycott Israeli products that come from the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

___________________________________________

Some young adults—and these are cradle Presbyterians we are talking about, engaged at every level in the church—even wanted to leave the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) altogether.

___________________________________________

Moreover, the Assembly chose not to backslide on a number of social justice fronts. It rejected the ideological silo-creating non-geographic presbyteries; attempts to soften the church’s commitment to diversity and representation; the proposal to eliminate medical benefits for women’s reproductive options; and efforts to overturn the 2010 Assembly decision to ordain individuals in same-sex relationships.

There were admittedly grave disappointments for many, most specifically in the Assembly’s decision not to endorse marriage equality or divestment in corporations profiting from the occupation of Palestine. But according to this interpretation, these disappointments, while unfortunate, were not unpredictable and offer strategic fodder for future efforts, especially considering that they lost by such small margins. Overall, therefore, the Assembly was a powerful example of the collective church entering into dialogue and sustained action.

Narrative Two: A Painfully Paralytic Assembly

The other interpretation, however, says General Assembly was a painfully paralytic exercise in the postponement of justice, avoiding anything too controversial or expensive, anything that might too radically envision a new way of doing church. It was an Assembly that often confused neutrality with the church’s calling to speak truth even when unpopular. This interpretation focuses primarily on the issues of marriage equality and divestment, both of which were recommended by their respective committees and by (an overwhelming majority of) young adult and theological seminary advisory delegates—and both of which concerned the integrity of the church: its ability to embody the very justice it so eloquently asks of society.

Perhaps even more frustrating than the failure to approve these measures was the fact that the Assembly did not make a direct decision on either issue. Minority reports supplanted the committees’ carefully deliberated majority reports, which then received no consideration on the floor—as if all the hard work of the committees did not matter. Instead, the Assembly voted (epitomizing for some a kind of paternalism) to pursue positive investment in Palestine, even though Palestinians themselves have said they need divestment, not investment. Instead, the Assembly voted to talk about marriage equality some more, despite the fact that the church has been having this conversation for decades now and has already had committees deliberate on the subject.

___________________________________________

If the committees revealed what church governance (and community) could be like, the Assembly plenary embodied many of the church’s current deficits: people talking past one another, cumbersome parliamentary procedure, the lack of young adult representation and power, the dominating ethos of anxiety, and a preference for surface-level unity over divisive justice.

___________________________________________

But these were not the only injustices of the Assembly, according to this interpretation. The Assembly, in what some deem capitulation to the myth of scarcity and the use of “stewardship of funds” as pretext for cowardice (while acknowledging current tough economic restraints), rejected opportunities to extend understanding and inclusion for two traditionally marginalized groups in the church: women and people of color. The Assembly refused to fund a major study, which would have assessed the status of women in the church and addressed power and compensation inequities, while also simply enabling the church to better resource and serve women in ministry.¹ The Assembly also replaced a call to “offer all” PC(USA) communications and resources in Korean, Spanish, and other languages, with the more ambiguous injunction to “provide basic accessibility of essential” information. That last item came from the Report of the Special Committee on the Nature of the Church in the 21st Century, which also saw its commitment to communities of new immigrants and people of color toned down by amending language that might alienate existing ministries and majorities (including the elimination of the specific phrase “white privilege”). Overall, to this critical interpretation, the Assembly represented a church so afraid of losing its past that it could neither imagine nor risk a possible future.

Of course, this duality is a generalization; there are plenty of reactions that exist along a spectrum between these two diagnoses. Moreover, there are justice-committed individuals who are thankful for the Assembly’s decision not to divest (believing it the improper course of action for peace or interfaith relations), or who are glad the Assembly did not adopt a position, such as marriage equality, not founded in church-wide consensus. But these interpretations do mark two distinct ways of telling the story of what happened at the General Assembly—and they split (with exceptions) along differences in age (as evidenced in this issue of Unbound). Among the justice-minded, more seasoned advocates and older adults tend to lean toward the first narrative, whereas young adults (18-29) and thirty-somethings tend toward the second narrative.

The Way Young Adults See It

During and since the Assembly, I have spoken with a considerable number of young adults (of which I am one). In fact, I had assembled a team of young adult writers who were going to report on the social witness of the Assembly. When I first reached out to them, they were excited and hopeful, eager to share their voices. After the Assembly, that all changed. Many expressed feeling quite devastated and angry, such that they felt unable to write. Some—and these are cradle Presbyterians we are talking about, engaged at every level in the church—even wanted to leave the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) altogether. They had poured their hearts into the Assembly, testified with courage and eloquence, worked tirelessly in their committees, all (some felt) to no avail. So, for a long time, I didn’t even hear back from some of the writers—they just didn’t have anything left.

This is surely not true for all young adults, and there are plenty, again, whose reactions fall along a wide spectrum. But nonetheless, this expressed interpretation should warrant intense concern among Presbyterians. It is an interpretation catalyzed by what was for many a deeply enriching, if sometimes tedious, committee experience. In committee, the young adult and theological seminary advisory delegates (YAADs and TSADs) had, not only a voice, but also a vote: a formal and equal power not present in the decision-making of the Assembly itself. Robert Trawick, in his Unbound article, notes, for instance, that the YAADs and TSADs had a significant influence on the work and decisions of the Middle East and Peacemaking Committee. He also states that it was the testimony of young Jewish women (not heard on the Assembly floor) that may have most significantly impacted the decision of the committee to recommend divestment.

___________________________________________

It was an Assembly that often confused neutrality with the church’s calling to speak truth

even when unpopular.

___________________________________________

Moreover, in committee, diverse viewpoints were held in civil tension. Real discussion occurred; community was even formed. Rev. Aimee Moiso, Moderator of the Civil Union and Marriage Issues Committee, describes in her Unbound article how their committee worked methodically and decisively to foster trust and relationship-building:

We ordered round tables for the committee to facilitate discussion and reinforce a sense of safety and comfort. During our first evening together, each of us wrote down our greatest hopes and fears, folded the papers closed, and passed them to one another to hold and pray over, acknowledging that our own hopes and fears might be directly opposed to the person for whom we prayed. We delayed entering into formal parliamentary procedure for as long as possible, believing that the extensive time in open conversation and listening would offer the greatest possibility to release pre-established opinions, hear the thoughts and ideas of many, and perhaps emerge into a sense of consensus ahead of the pressure of final decision-making.

If the committees revealed what church governance (and community) could be like, the Assembly plenary embodied many of the church’s current deficits: people talking past one another, cumbersome parliamentary procedure prone to some manipulation, the lack of young adult representation and power, the dominating ethos of anxiety, and a preference for surface-level unity over divisive justice.

The YAADs also had some powerfully transformative and meaningful community-building experiences among themselves, even across significant differences and opinions. Among themselves, they saw the possibilities for a compassionate, engaged, inclusive, and welcoming church—in bold contra-position with the “balancing” of the Assembly.

What the Young Adult Experience Means for the Church

Of course, given the reactions of the more veteran justice advocates, it is plausible to infer that much of the intensity of the young adult narrative is due to a lack of sufficient experience and even training in the (slow, organized, and strategic) nature of social change. But the difference also represents a profound shift in cultural expectation. We young people are not, for good or ill, content to wait for equal power, justice, and change. Yes, it is partly impatience. But it is also the recognition that postponed justice is injustice; that justice is urgent because people, real lives, are hanging in the balance; and that if the church is to have a significant future, all must have a say in its creation.

___________________________________________

The good news is that many of these young people are so angry that they are intent on staying in the church and working for change.

___________________________________________

Injustice has always been painful. Courageous and tenacious members of older generations have stayed, despite inequality, despite injustice, because they wanted to work for the kind of church they knew we could and should be. They believed the church was worth the pain. But here’s a chilling thought for you: for many young people, the church, this church, is not worth it. There are plenty of other options, plenty of churches that have taken greater strides in justice and equality. At one time, society was as pervasively anti-LGBT as the church was, and so LGBT equality advocates expected a fight. But young people often these days do not share that cultural expectation. Society has changed. While we still have a long way to go in creating a society that embraces and offers equal rights to people of all identities, states are legalizing same-sex marriage and even the infamous Chick-fil-A recently cancelled its donations to anti-LGBT organizations. Young people expect equality, and they expect the church to take the lead. When it doesn’t, the church appears to be an awkward, recalcitrant relic concerned more with entertaining nostalgia than with the radical justice, faith, and community of the Gospel.

The good news is that many of these young people are so angry that they are intent on staying in the church and working for change. The bad news is that it may not be appropriate anymore for the PC(USA) to ask how it can attract new youth; it has to focus on how it’s going to keep the ones it already has. Because, according to the votes, marriage equality and stronger measures for justice will happen—if young people stick around and if there is still a church with the courage to reform not only the world but also itself (and that’s a big “if”).

See more articles like this one from the Oct 2012 issue, “The Backstory of General Assembly”

________________________

Notes

¹ A limited amount of previously designated but unused funds may be available for some of the tasks of the study.

The Rev. Patrick David Heery, 27 years old, is the Managing Editor of Unbound and an ordained Teaching Elder (formerly Minister of Word and Sacrament) in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). He is a staffperson for the Advisory Committee on Social Witness Policy. He earned his Master of Divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary (2011) and a Bachelor of Arts in both English and Classics from Ohio University (2008).

Unbound Social