The Long Road to Justice

According to renowned justice theorist John Rawls, a just society must be premised on mutual consent—only after which can the structure of society be decided upon by those choosing to live together as a society.[14] There was no consent given by the Wiyot tribe—they were not historically invited to be a part of society with settlers; they were forcibly displaced, murdered, swindled by un-ratified treaties, and ultimately assimilated as “Americans.”[15] The state, with its foundations in coercion, not consent, is in no position, therefore, to offer terms of justice and reconciliation. Those terms can come only from the party originally denied consent.

In fact, strides have been made, but only by the leadership of the victims themselves. While early efforts successfully focused on political rights, tribal elder Cheryl Seidner began to focus on cultural rights in 1992, beginning with the Indian Island Candlelight Vigil. The vigil is held on the last Saturday in February, the historic annual date of the World Renewal Ceremony, and is intended both as a memorial for the hundreds who were killed in the massacre, as well as “a healing ceremony, to help heal the rift in the society locally and around the country.”[16] Bridging the gap between irreparable injustice and the fact of mutual social cohabitation, the victims have become, in a sense, the victors over history, offering what could never be offered by the state—precisely that bond of cooperative social compact fundamentally required for a “just” society.

With that foundational requirement met, justice then demands the fair distribution of political and economic rights and resources. With the successful bid for Tribal status achieved in 1990, the Wiyot received the long overdue protections that gave them tribal sovereignty, land trusts (which at the time amounted only to the 20 acres purchased on their behalf in 1900), and equal liberties as citizens of both the U.S. and of the Wiyot nation. These rights have given them the necessary equalities and legal protections to begin the battle for the final element of distributive justice in land rights and, by extension, rights to their own history in cultural and human artifacts.

Also begun in 1992, the Sacred Sites Fund has been seeking donations and applying for grants to purchase back parts of Duluwat Island for almost 20 years. By all accounts, the Wiyot have a right to demand their land back. And yet, for the sake of cooperation and benevolence, they offer to purchase the land stolen from them. In 2001, 141 years after the massacre, the Wiyot tribe was successful in purchasing back the first 1.5 acres of the island—the site of the village of Tuluwat where the massacre had occurred.

Subsequently, the City of Eureka, in a landmark decision unparalleled anywhere else in California, gifted back 40 acres of land to the tribe in 2004, and returned another 20 acres in 2006. To date, the tribe now owns the 61.5 acres of land north of the span of Highway 255. Yet the city still owns the majority of the island. There is only a small portion of the island (10%) that is privately owned, and as Tribal Spokesperson Cheryl Seidner has said: whatever holdings the city still has, “we [eventually] want it.”[17]

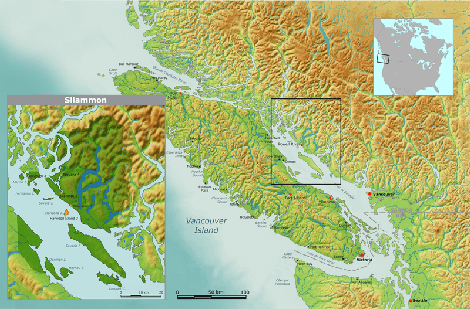

Is it enough? The Wiyot land holdings, cultivated, planted, and responsibly kept up until its unlawful seizure in the first half of the 19th century, extended “from Little River to Bear River, out to Chalk Mountain and to Berry Summit.”[18] By all accounts of even European standards, these 600 square miles (384,000 acres) were inhabited and owned by the Wiyot people.[19] They never offered to sell the land, nor were they given just recompense for its unlawful seizure.

In the aftermath of the near obliteration of their people and nearly total usurpation of their lands, they have rebuilt their Tribe (today numbering 600 on the tribal registry), and have been granted an 88 acre reservation alongside the original 20 that was purchased for them. They have bought back 1.5 acres of Duluwat Island, and were gifted back another 60 acres by the city of Eureka. With the Yurok and Hupa people, they have been granted a further 31 acres five miles east of Arcata, yet the governmental holdings of even the sacred center of their world still vastly surpass what they themselves have been “gifted” back.

Though the strict standards of distributive justice have by no means been satisfied, the Wiyot seek to restore Duluwat Island one parcel at a time, spending as much time, effort, and funds as needed to rehabilitate the soil,[20] repopulate native species of plants, rebuild a cultural center, and a dance hall, and to someday reconvene the World Renewal Ceremony and Dance—which hasn’t been danced since February 25, 1860.

Unbound Social