Time for the United States to Step Up

I am convinced that a deeper commitment is owed to our first peoples. UC Berkeley alone stores over 10,000 native Californian artifacts,[21] likely including human remains robbed from graves on Duluwat island itself. Local governments, the State Government, and the Federal Government still retain an incredible wealth of Native lands—it is neither protected for national park use, nor is it in use. Lands that can be returned should be. Lands that cannot be returned should be justly (as much as can be achieved 150 years or more after the fact) transferred[22] through an agreed upon price. Relics and remains removed from Tuluwat and other Native Californian lands and burial grounds must be returned, “loaned,” or purchased by un-coerced agreement. The balance of distributive justice in this case does not simply lie in the gratitude of a people our state nearly succeeded in destroying; it lies in our collective willingness to act in accord with our own conceptions of what is right, and to establish policies that ensure that justice is accomplished.

From the start, policy makers must be equally represented from tribal and non-native populations, and we must be willing to look at the establishment of these policies as if the tables were turned, as if we did not know whether we were Wiyot or of non-native descent. How would we like it if someone dug up our grandparents, stole their rings and necklaces, and put their bodies and clothes on public display? How would we feel if we came home one day to find strangers had taken up residence in our homes, and that the government allowed it—even sanctioned it? How would we want to be treated in the formation of policies dealing with these injustices? Perhaps, as Rawls suggests,[23] this classic reversal could offer a real way to judge the justice of policies fairly. I for one would not want to be treated as we have treated Native Californians. It is simply and classically unjust.

The Rev. Austin Leininger is an Episcopal Priest in the diocese of Northern California currently pursuing a PhD in Ethics and Social Theory at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Austin’s connection to the Wiyot tribe comes from working with the tribe to arrange a seven day mission trip during which Austin and a group of about twenty-five youth and young adults were allowed to work side by side with tribe members in the clean up and rehabilitation efforts on Indian Island. Austin is married, father to three children, and when he’s not stuck in a book or celebrating Eucharist he’s sure to be found pursuing one of his many hobbies out in the natural world.

The Rev. Austin Leininger is an Episcopal Priest in the diocese of Northern California currently pursuing a PhD in Ethics and Social Theory at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Austin’s connection to the Wiyot tribe comes from working with the tribe to arrange a seven day mission trip during which Austin and a group of about twenty-five youth and young adults were allowed to work side by side with tribe members in the clean up and rehabilitation efforts on Indian Island. Austin is married, father to three children, and when he’s not stuck in a book or celebrating Eucharist he’s sure to be found pursuing one of his many hobbies out in the natural world.

[1] Sources vary from 80-250 – it is unclear whether the inflated numbers include other massacres of Wiyot at Rancherias along the Eel river on the same night. Wiyot sources cite the Indian Island Massacre at “over one hundred” (“Wiyot Sacred Site Fund,” nd, accessed 10/28/11, [online resource] available from http://www.wiyot.com).

[2] Jerry Rohde, “Genocide and Extortion: 150 years later, the hidden motive behind the Indian Island Massacre,” North Coast Journal, Feb. 25, 2010, (North Coast Journal Website accessed 10/28/11) [online resource] available from http://www.northcoastjournal.com/news/2010/02/25/genocide-and-extortion-indian-island/

[3] CA Indian Library Collections, CA Pre-contact Territories Map [online resource] available from http://www.kstrom.net/isk/maps/ca/calprecontact.gif and CA Tribal Linguistic Groups [online resource] available from http://www.mip.berkeley.edu/cilc_images/bibs/maps/lingmap.gif.

[4] Betty Goerke, Chief Marin (Berkeley:Heyday Books, 2007), pp. 170-178.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Paula Giese, “California Indian Treaties” (Native American Indian Resources Website, 1997, accessed 10/28/11), [online resource] available from http://www.kstrom.net/isk/maps/ca/caltreaties.html.

[7] Estimates range from 1500-2000 tribal members in 1860 prior to the massacres (Wiyot Tribal Website, nd, accessed 10/28/11), [online resource] available from http://www.wiyot.com/cultural.

[8] Cheryl Seidner, interview with North Coast Journal in “The Return of Indian Island – Restoring the center of the Wiyot World” (North Coast Journal Website, 1 July 2004, accessed 10/28/11) [online resource] available from http://www.northcoastjournal.com/070104/cover0701.html.

[9] Cheryl Seidner, interview with Austin Leininger, “Avenue of the Giants Mission Trip” (Unpublished personal notes, 17 June 2010).

[10] Ibid.

[11] An estimated 2000 cubic yards had been lost between 1913 and 1985 – more recent estimates have not been found to be published. (“Tuluwat Project,” Wiyot Tribal Website, nd, accessed 10/28/11 [online resource] available from http://www.wiyot.com/tuluwat-project).

[12] A single individual “amateur archeologist” is said to have looted over 500 gravesites (Ibid.).

[13] “Genocide and Extortion,” researched by Jerry Rohde in Humbolt Times from 1854-1861, Northern Californian 1860, SF Daily Evening Bulletin 1860, Butte Democrat 1860, and personal interviews with massacre survivor, Jane Sam.

[14] The Contractarian basis for Rawls theory, stemming from John Locke’s definition of the social contract insists that members contracting to be in society do so as free and consensual rational agents (John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, [Cambridge:Belknap Press, 1999, orig. Harvard University Press, 1971], p.10).

[15] Seidner, North Coast Journal, 2004.

[16] Wiyot Blue Lake Tribal Business council, “Wiyot History,” (Wiyot History Webpage, 1996, accessed 10/28/11) [online resource] available from http://www.kstrom.net/isk/art/basket/wiyot/wiyot.com.

[17] Seidner, North Coast Journal, 2004.

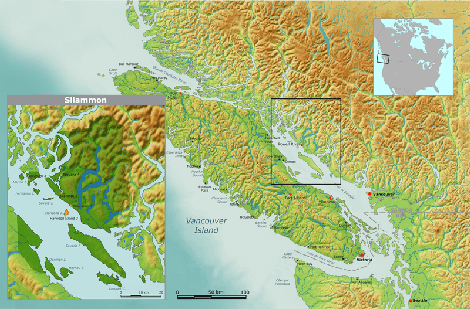

[18] Ibid. (map available from http://www.humboldt.edu/cicd/map.html).

[19] According to property acquisition defined by John Locke, they improved the land and put their labor into it before anyone else, thereby acquiring it justly (John Locke, Second Treatise of Government [Kindle Edition, 2011], 13).

[20] Dioxin is the main issue, contaminating over 300,000 tons of topsoil that has to be removed to remote toxic storage – a lasting effect of the ship yard. The land underneath (also contaminated) must then be geocapped before the soil can be replaced from an outside source. (“Avenue of the Giant’s Mission Trip,” 2010).

[21] Alan Leventhal, Bureau of Indian Affairs (July 30, 2001 report, accessed 9/9/2010), [online resource] available from http://www.bia.gov/idc/groups/xofa/documents/text/idc-001659.pdf.

[22] According to the social contract (both Locke and Rousseau) just transfer of property is premised on just acquisition (Locke, 20-21). Rawls affirms the right to inheritance (Rawls, 245) as well as the right to buy and sell just holdings in free commerce via “legal definition of property rights” (Ibid., 247) – this, he suggests, fulfils the first principle of justice in equal liberty. The Wiyot are the only claimants to have come about the acquisition of their land justly. They must therefore agree to a price for its transfer before the series of historic transfers can be justified and the current owners legitimated. (While Rawls also suggests ideal institutions to help ensure wide distribution of property, this is attached to the second principle of justice [Ibid.], which is subordinate to the first principle first having been fulfilled [Ibid., 53]).

[23] The Veil of Ignorance, (Rawls, 118-119).

Unbound Social