View and print as PDF

View and print as PDF

Prefatory Contextual Remarks

Kenya

Post-colonial Kenya saw its first direct elections in 1957. The Kenya African National Union (KANU) formed a government just before Kenya assumed independence in December 1963. KANU ruled under a single party constitution from 1964 to 2002, with just two presidents: Jomo Kenyatta (1964-78) and Daniel arap Moi (1978-2002). The regime was generally regarded as undemocratic and in violation of human rights, particularly through the suppression of political dissent. In 2002, the new National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) won the presidency, marking a free election and significant turning point for the country.

Timothy Njoya

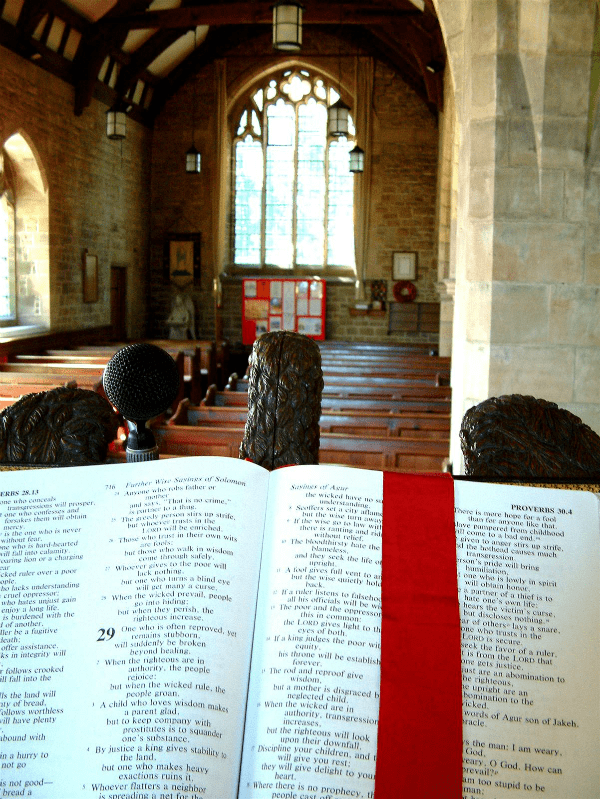

From the pulpit to the streets where he has joined like-minded Kenyans in peaceful demonstration, Rev. Njoya has constantly demanded freedom from the political dictatorship in Kenya. This has not been without a sharp and intimidating response from the Kenyan authorities, who have often accused Rev. Njoya of subversion. Following a sermon in October 1986, the President accused him of producing subversive pamphlets in the guise of Sunday sermons. His outspokenness has often resulted in detention without trial.

On July 7, 1997 while at a pro-democracy gathering at the All Saints Cathedral in Nairobi, the police forcibly invaded the Cathedral, badly injuring Rev. Njoya, among others. On June 10, 1999, while at a pro-democracy procession outside Parliament in Nairobi, Rev. Njoya was the victim of a merciless beating from a private army hired by state operatives. He was brutalized while the police stood by and watched.

In his efforts to create a culture of freedom, justice and equality in Kenya, Rev. Njoya has had to take on not only the mighty monolith that is the state in Kenya but also the church, from where he has been variously disowned at critical moments.

– The International Center for Human Rights and Democratic Development

Pulpit as a Forum for the Restoration of Government

By Timothy Njoya

In Kenya, the civil society abdicated its stewardship of governance to the government, and the government failed to become government. These failures were preaching events in which the pulpit became the forum raising democratic awareness about the lack of democracy in our society. These events awakened Kenyans to know that their faith could help to establish a caring, sustaining, and nurturing system of governance in which the government would see human beings in the same light as God sees them—unlike the government inherited from colonialism, which saw society as cheap or worthless capital.

At the time, though, the church did not have a faith by which to articulate the whole Gospel. The sermons filled this vacuum by expounding faith as the context in which all other contexts are changed. They communicated ideas and issues so worthy of national and international debate that they provoked the church and the government to justify their existence.

A ‘Subversive’ Sermon

On July 8, 1984, I preached a sermon on the Gospel of Luke, appealing to people to pray for outcasts. When Parliament returned from recess,

Mr. Sifuna rose and told the speaker, Mr. Fred Mati, he had an important communication to make. He said that on July 8, 1984, the Rev. [Njoya] of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa (PCEA), delivered a sermon on radio and television, making extremely perturbing statements… [Rev. Njoya] said some quarters of the press seem to rejoice at the suffering of another Kenyan. He asked the president to invite, as Jesus did, the lost sheep… and release those in detention, to invite Ngugi wa Thiong’o [Kenyan author imprisoned by the government and identified by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience] back to the country. (The Nation, July 19, 1984, p. 1).

In response, the Ministry imposed a ban on live broadcast and began censoring sermons before they aired on the radio or television in order to avoid the transmission of “subversive” ones. By that evening, technicians from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting had ripped from the walls of the church the public address system connecting the church with the voice of Kenya. When the Minister of Broadcasting defended my rights to pray, he lost his job.

___________________________________________

The civil society abdicated its stewardship of governance to the government, and the government failed to become government. These failures were preaching events in which the pulpit became the forum raising democratic awareness about the lack of democracy in our society.

___________________________________________

The Minister of the State explained that the government had always allowed the church to worship without interference because the church had confined itself to just that: worship. He added that worship must be “complimentary to the government policies and aspirations, in the interest of law and order.” So, he said, “Rev. Njoya went beyond the limits and interfered with government actions. His preaching was not in keeping with the spirit of peace, love, and unity” (The Nation, July 20, 1984).

On Friday, July 20, 1984, the Secretary General of the PCEA telephoned me and demanded a copy of the sermon. I immediately drove to his office and sat silently as he read the text. I asked him, “Isn’t that Luke’s theology about Jesus?” He furiously showed me the door and said, “Go back to your work while I think of the answer.” In a few hours time, the Secretary General entered my office and delivered me a letter. I offered him a seat and he refused. He watched me read the letter. My lips shook as I read. I sweated and developed a migraine before reading the last paragraph. The letter asked me to move out of the church. I was instantly dismissed and another minister was brought in to take my place.

This hit me harder than my conflict with Parliament. How would I feed my family? I knelt down and prayed for an hour.

The Secretary General’s press statement declared, “Pulpits are for the Good News and not for political motives… Pastors who misuse pulpits or their licenses for ill motives will be doing so at their own risk” (The Nation, July 21, 1984). But when the decision went before the full Presbytery, the General Secretary had the shock of his life. The Presbytery asked an elder from my congregation to read the script of my sermon. After he finished, everybody except the two Head Office officials shouted, a-a-a-men. The elder from Mombasa stood up and said, “The Presbyterian Church gets its theology and government from the Bible and the Holy Spirit, not from the State.”

That day, the Nairobi Presbytery did not let the civil society down by endorsing the Head Office’s shoot-your-wounded-soldier attitude. The Presbytery stood by me.

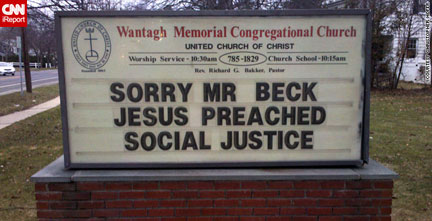

Some Context: Can subversion come from the house of God?

What you need to understand is that the Baba Taifa had ruled Kenya for thirty years. Kenya, during and after colonialism, had never created a forum for open debate in the government. When JM Kariuki wanted to introduce debate in Parliament, asking why Kenya should become a country of ten millionaires and ten million destitute, he was picked up by police within the precincts of Parliament and murdered. Hence, by default, debate in Kenya began in the pulpit.

___________________________________________

By that evening, technicians from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting had ripped from the walls of the church the public address system connecting the church with

the voice of Kenya.

___________________________________________

What you also need to understand is that when the British, Belgian, Italian, Spanish, French, Dutch, and German governments apportioned Africa to each other (in the 1884 Berlin Conference), Maritime Trade and not democracy was the prime mover. When the wind of change came and Africa had to be independent, nationalism and imperialism brokered constitutions without participation by the populace. Independence was mere ceremonial arrangement. No thought was given to women’s rights or self-determination. The new constitution simply confirmed colonial laws which treated Africans as sub-human, soul-bearing objects and women as men’s property. The church and the government got used to thinking that creativity, debate, and the questioning of the status quo were expressions of sin and insurrection.

To this point, President Moi (President of Kenya, 1978-2002) once asked, “How could subversive documents come from the house of God?”

Continue reading on the next page…

Unbound Social