As Reformed Protestants, we are people of the book. We ground ourselves in The Bible. While we may no longer be rigidly sola scriptura, we nonetheless often find ourselves more comfortable in appeals to text than appeals to experience.

There is much value and much danger in this way of approaching matters of faith. At our best, by grounding ourselves in scripture we open ourselves to rich tradition, informed by the ethic of radical love taught to us by Jesus Christ and explored by many generations. The danger lies in using the text as insulation: enclosing ourselves off from real dialogue and learning, and in assuming that we have a unique claim on truth. Some passages of scripture point us toward this sort of exclusivism more than others. For me, among the most perplexing, challenging, and at times deeply troubling is John 14:6:

Jesus said to him, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.

Because this verse has been used for so long and in so many settings to proclaim truth as the exclusive property of Christians and to consign non-Christians to irredeemable error (and worse), it has been one that I tend to avoid. Living as I do in a mixed faith household, the idea of an essential superiority of Christian faith has little appeal.

___________________________________________

The stark choice of “Christ or damnation” has been the subtext…of many a sermon. [I]n an age when interfaith dialogue has…become an important feature of our faith lives, one wonders what to do with this imposing legacy.

___________________________________________

And yet, there John 14:6 sits. The verse has animated much of the revival tradition of Christianity in the United States. The stark choice of “Christ or damnation” has been the subtext, if not the text, of many a sermon. And in an age when interfaith dialogue has, at least in some religious circles, become an important feature of our faith lives, one wonders what to do with this imposing legacy.

That the Christian church has long been uncomfortable with some of the implications of its own exclusivist theology is evident in its early embrace of the doctrine of the “harrowing of Hell.” Based on an account in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, it was proclaimed as dogma by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. The harrowing of Hell doctrine supposed that Christ, after his death, descended into Hell to rescue from its torments those patriarchs, such as Moses and Abraham, who had been condemned merely by being born before the advent of the Messiah. Dante references this in the fourth Canto of the Inferno, when Virgil, speaking of Jesus, says:

He carried off the shade of our first father,

Of his son Abel, and the shade of Noah,

Of Moses, the obedient legislator,

Of father Abraham, David the king,

Of Israel, his father, and his sons,

And Rachel, she for whom he worked so long,

And many others – and He made them blessed.[1]

Karl Rahner, the 20th century Catholic theologian was similarly disturbed with the apparent damnation of great masses of humanity His solution was his concept of the “anonymous Christian.” For Rahner, those who “have no explicit knowledge of the fact that [their lives are] oriented in grace given salvation to Jesus Christ,”[2] may still achieve salvation. Those who live in a manner congruent with Christian faith and love, can be, in essence, adopted as Christians. Thus non-Christians whom we admire and whose virtues we acknowledge fall under the banner of Christ’s salvific work, even when they do not understand or acknowledge Christ’s work in their lives.

Although these attempts at some version of inclusivity certainly move us forward from a starkly exclusivist understanding of truth, they nonetheless continue to presuppose the superiority of the Christian vision, even as they create loopholes for those whose truths may be different. There is a lingering condescension in this parsing of soteriology. An “even though” remains in the embrace of other traditions – “We love you even though you are [Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, etc.].”

___________________________________________

Especially when exploring the truth about God’s work in our world, it might behoove us to understand the limitations of our knowledge, how it is bound by time, by culture, by social location.

___________________________________________

More persuasive and helpful, at least to my ears, is the version of “conjunctive faith” described by James Fowler in his seminal work Stages of Faith. Fowler proposes a developmental understanding of individual faith lives, growing through uncritical acceptance and later critical engagement, as our minds and our understandings of self evolve. Conjunctive faith, Fowler writes, “is ready for significant encounters with other traditions than its own, expecting that truth has disclosed and will disclose itself in those traditions in ways that may complement or correct its own…”[3]

Fowler goes on to describe a humility of faith, born not out of any lack of conviction about one’s own tradition, but rather out of a sense that truth may be more multivalent than we are often taught. He writes:

…the Conjunctive stage learns to bring a principled openness to encounters with the strange truths of other religious and cultural traditions. I do not here speak of a wishy-washy sense of openness in which one has no strongly held convictions. Rather, I refer precisely to its opposite. Conjunctive faith…leads to a readiness for serious and mutual dialogue with traditions other than its own. It is confident that new depths and corrected perceptions of the truths of its own tradition can be the result.[4]

Especially when exploring the truth about God’s work in our world, it might behoove us to understand the limitations of our knowledge, how it is bound by time, by culture, by social location. “[P]roperly we stutter,” Fowler writes, “when we speak of the Divine.”[5]

___________________________________________

[C]losing myself off from the wisdom others have gained from their particular journeys, inside or outside of Christianity, seems not only foolish, but a rejection of blessings being placed in front of me.

___________________________________________

So, back to John. When we start with what comes before 14:6, we can reorient our hermeneutics. In the beginning of the chapter, Jesus has reassured his disciples that in God’s house there are many dwelling places (v. 2). But the passage in question comes as a response to Thomas’ question in v. 5, “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” Jesus’ statement is a reply to Thomas, and by my reading it most importantly refers to how we, as followers of Christ, are to model our lives. And Jesus makes clear that abstract belief is less important than the fruits of faith. He says “Believe in me that I am in God and God is in me; but if you do not, then believe in me because of the works themselves.” If Thomas wants to know where Jesus is going, walking in the footsteps of Jesus and modeling the love of Jesus seems to be paramount.

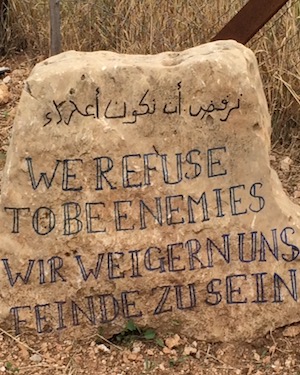

Photo by Diane Fitch

When I come to a dialogue with interfaith partners, I need to be clear about the gifts I bring, as a Christian, to the conversation. The narrative that I embrace in Christian scripture allows me to speak as one who claims and is claimed by Jesus Christ. My entry point into the radical love commanded of us by our Creator is the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. I am obedient to my call by attempting to model that ministry, even while being aware of my own limitations. Christian scripture makes Jesus’ ministry live for me and allows me to lay it on the table as my contribution to the furthering of God’s commonwealth here on earth.

If I understand my faith in this way, my narrative opens up dialogue rather than closing it at the beginning with some claim of hegemony. If, however, I use scripture as a scalpel to cut away those who claim a different narrative, I believe I am being unfaithful to my own tradition. It is difficult to be Reformed and constantly reforming when you only listen to one set of voices.

And that is where I am left with the question of the nature of Christian truth. I don’t know how salvation works, but I assume God does. I do know that, as followers of Jesus Christ, we have been given the very explicit command to love. Working at living out that command is work enough, without passing judgment on the faith journeys of those who follow a different path than I do. And closing myself off from the wisdom others have gained from their particular journeys, inside or outside of Christianity, seems not only foolish, but a rejection of blessings being placed in front of me.

In his latest recording, Bone on Bone, Canadian singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn tackles the old gospel tune “Twelve Gates to the City” popularized by Rev. Gary David, Pete Seeger, and others. In a new verse, Cockburn sings:

No matter which tribe you’re born to there’s a way in for you.

Come from any quarter – you can be a citizen too

‘Cause there’s twelve gates to the city, hallelu.

There are worse theologies to embrace.

***

[1]Dante, The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri: Inferno, trans. Allen Mandelbaum (New York: Bantam, 1980) Canto iv, lines 55-61.

[2]Karl Rahner, Theological Investigations, Volume 14, trans. David Bourke (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1976) 283.

[3]James Fowler, Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. (New York: HarperOne, 1981, 1995) 198.

[4]James Fowler, Faith Development and Pastoral Care (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987) 73.

[5]Ibid, 72.

Author Bio: Dr. Robert Trawick is an Associate Professor of Philosophy and Religious Studies at St. Thomas Aquinas College in Sparkill, NY. His research interests include Reformation theology and the intersection of theology and labor. He has written most frequently on the Social Gospel movement. He lives with his wife Amanda and son Owen in the lower Hudson Valley, where he is an ordained Presbyterian elder.

Read more from this issue, Make America Just. Period. (A Moral Platform for the Christian “Justice Voter”).

Unbound Social