I grew up in a semi-rural, lower-class area of mid-Michigan called Bay County, where no one talked about going to college or having a “career.” My parents had moved to Bay County from a poor region of the Upper Peninsula, where my father was taught that being Native American made him an inferior being. My family was not religious, but I have always had a mystical impulse; we owned a Catholic Family Bible; and sometimes we got to mass. That was just enough to get my attention. Actually reading the Bible seemed impossible to me—How were you supposed to assimilate such a sprawling mass of whatever it was? And I had no idea of Christian doctrine.

I grew up in a semi-rural, lower-class area of mid-Michigan called Bay County, where no one talked about going to college or having a “career.” My parents had moved to Bay County from a poor region of the Upper Peninsula, where my father was taught that being Native American made him an inferior being. My family was not religious, but I have always had a mystical impulse; we owned a Catholic Family Bible; and sometimes we got to mass. That was just enough to get my attention. Actually reading the Bible seemed impossible to me—How were you supposed to assimilate such a sprawling mass of whatever it was? And I had no idea of Christian doctrine.

But I was drawn to Christ by the image of the suffering God in Catholic iconography. Jesus crucified, the God-figure who responded to evil and oppression with self-sacrificing love, gave me a religious ideal—a sign of transcendence that broke through my everyday horizon of lower-class culture and the next game. This ideal took on a searing ethical and spiritual meaning in the stunning witness of the Civil Rights movement.

I came of age in the climactic years of the Civil Rights movement. Long before I understood much of anything about politics or religion, the formative figure for me was Martin Luther King Jr. He was the exemplar of the peacemaking and justice-making way of Jesus; the Christ-figure of our time; the one who lived in the Spirit of Jesus and died for us. That was the sum total of my religious worldview when I squeaked into college, mostly to play sports. Forty years later, it is still my bedrock, which sustained me through ten years of watching my young beloved spouse die to cancer.

___________________________________________

On the lecture circuit I meet people every week for whom Christianity is a ruined word. They ask me nicely, or with puzzlement, or with hostility, why I am still a Christian. I try to explain that I was drawn… by the experience of subversive peace and grace of Christ.

___________________________________________

On the lecture circuit I meet people every week for whom Christianity is a ruined word. They ask me nicely, or with puzzlement, or with hostility, why I am still a Christian. I try to explain that I was drawn long ago into the spirit and way of Jesus, which draws me like a magnet into its gravitational force. I am held by the gospel picture of the divine Word entering the world, and by the experience of the subversive peace and grace of Christ, the meaning of suffering, the challenge to oppose every form of exploitation and violence in the world, the willingness to give my life to others and the promise of new life that it brings. These experiences shape my understanding of how I should live.

Good theology does not say that unearned suffering as such is redemptive. We are indebted to feminist and womanist theology for stressing this point, and I believe that Dr. King got this right. Having suffered much, King sought to make his suffering a virtue to save himself from bitterness and to call white racists to repentance. In his experience, unearned suffering offered the opportunity to turn suffering into something redemptive. Suffering itself was not redemptive, but suffering could be made redemptive when oppressed people struggled against it in the name, and way, and spirit of Jesus.

Several of my books have made a case for developing decentralized forms of economic democracy: public banks, community finance corporations, community land trusts, worker and community owned enterprises, cooperative networks, and most importantly, mutual-funded holding company models that are more entrepreneurial than cooperatives and are better able to scale up. I do not believe that the factors of production trump everything else. But I do believe that those who control the terms, amounts, and direction of credit have a huge say in determining the kind of society that the rest of us live in. Anything that democratizes the process of investment is a gain for the common good.

Dr. King was devoted to three interlocking social justice causes: racial justice, economic justice, especially anti-poverty activism; and anti-militarism. That is still a compelling list of priorities to me, except that all of these commitments have to be conceived as inseparably related to struggles for gender and sexual justice, and ecological flourishing.

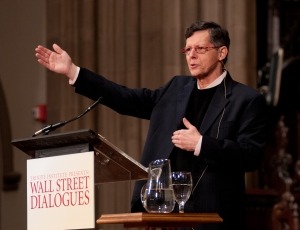

Watch Gary Dorrien’s “Wall Street Dialogues: What is a just distribution of wealth and power?” at Trinity Wall Street Church!

____________________________________________

Gary Dorrien is the Reinhold Niebuhr Professor of Social Ethics at Union Theological Seminary and Professor of Religion at Columbia University. An Episcopal priest and lifelong athlete, he was previously the Parfet Distinguished Professor at Kalamazoo College, where he taught for 18 years and also served as Dean of Stetson Chapel and Director of the Liberal Arts Colloquium. He has two books forthcoming in early 2012: Kantian Reason and Hegelian Spirit: The Idealistic Logic of Modern Theology (Wiley-Blackwell), which makes an argument about the impact of Kantian and post-Kantian idealism on modern religious thought, and The Obama Question: A Progressive Perspective (Rowman & Littlefield), which makes a progressive critique and defense of Barack Obama¹s presidency.

Unbound Social