From False Dichotomies to Gospel Faithfulness

Considering what it might take to merge the priorities of evangelism and social justice into one missional conviction that embodies them both. By Darrell Guder View and print as PDF

View and print as PDF

Toward the end of the 1980s, the new, reunited Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) carried out a national discussion of its goals and priorities. The outcome of the process was the identification of two priorities for the denomination: evangelism and social justice. Since the theme “evangelism” had received little attention at the national level of the church in preceding decades, I was grateful that it re-appeared in our official language. But I had to wonder what was going on when these two themes were placed next to each other as separate priorities.

Toward the end of the 1980s, the new, reunited Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) carried out a national discussion of its goals and priorities. The outcome of the process was the identification of two priorities for the denomination: evangelism and social justice. Since the theme “evangelism” had received little attention at the national level of the church in preceding decades, I was grateful that it re-appeared in our official language. But I had to wonder what was going on when these two themes were placed next to each other as separate priorities.

What kind of evangelism is referred to if it can be distinguished from social justice? What is the character of the social justice that can be separated conceptually from evangelism? Since I was about to take a faculty appointment in mission and evangelism, I was obviously interested in the thinking that was behind these choices. I soon discovered when I came to Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary in 1991, that the separation of the two themes was not merely academic or definitional. It became clear in many conversations that our denomination was often perceived as made up of two major factions, one that grouped itself around “evangelism,” and another around “social justice.” The operative assumption appeared to be (and still is for many, I fear) that those who are deeply committed to the church’s evangelistic mission have little interest or commitment to social justice, and those who take social justice concerns seriously are not very energized by the themes or practices of evangelism.

More than Personal Salvation

These two priorities, set in this pattern of parallel commitments with little interaction between them, represent a profoundly disturbing distortion of the very nature and mission of the church of Jesus Christ. This distortion I call the “mission–benefits” dichotomy. It reduces the broad sweep of the Gospel message to the narrow concern for a person’s individual salvation—a relationship with God now and the assurance of salvation hereafter. The individual focuses on receiving the benefits of salvation while ignoring or diluting the missional vocation that always accompanies the call to follow Christ. The primary focus is on the vertical, with little regard for the horizontal dimensions of the Gospel. Salvation is understood as a status rather than a process. The church is understood as the community that offers and then administers individual salvation.

Missing from this reductionist understanding of the Gospel are the reality and claims of the Kingdom of God as a radically different ordering of life in obedience to Jesus Christ as Lord. Evangelism becomes primarily the recruitment of members of the church, and the church itself becomes the collection of people for whom the institution is to provide the services that continue to guarantee their salvation. Lost is the biblical emphasis on the missionary vocation of the church and the witness character of each Christian’s calling.

___________________________________________

It is far easier to focus on the question of who is saved and who is not than to confront the challenge of Christ’s claims to be Lord over every area of our lives, personally and corporately.

___________________________________________

The church does not exist for the sake of its members’ salvation. Its evangelism is not primarily a program to guarantee its continuing existence as an organization. The church is missionary by its very nature, and each Christian is marked by Christ’s sweeping promise, “You shall be my witnesses.”

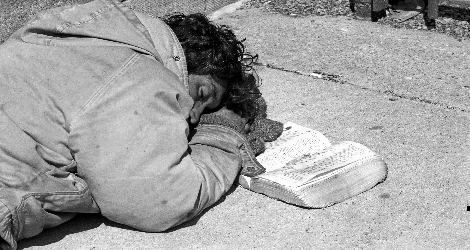

The benefits of knowing God’s love in Christ cannot be separated from the vocation to become witnesses to that healing love in the world into which Christ sends his church. The mission of God in Christ has the whole world in view. Evangelism is communication of good news, meant to be communicated to everyone everywhere, like the sower of the Gospel parable spreading his seed on every kind of soil as he crosses the field. The over-arching Biblical description of the church’s purpose is “witness,” which is public demonstration of what God has done and is doing in Christ so others may make decisions about the claims of this message. It is far easier to focus on the question of who is saved and who is not than to confront the challenge of Christ’s claims to be Lord over every area of our lives, personally and corporately.

The Problem with Social Justice

Our current concern with social justice could and should be the corrective to such reductionist understandings of evangelism. It should be the way in which we are reminded of the cosmic scope of the Gospel, the claims of Jesus that his coming means radical transformation of every level of society, starting with the weak, the blind, the lame, the imprisoned, and the marginal. The priority of evangelism must be pervasively shaped by the Kingdom claims of the Gospel that are at the heart of what Christians mean by justice. But it is difficult to see that happening if our understanding of social justice is defined without its essential reference to our evangelistic mandate.

Separating social justice from the Evangel perpetuates a profound reductionism of what we mean by such justice. How is social justice to be a witness to the radical good news of God’s love in Christ? What is the relationship between what we mean by justice and the righteousness of God? If the radical claims of the Lordship of Christ tend to be diluted in evangelism reductionism, is not something similar also happening on the social justice side of the debate? My hunch is that this reductionism has to do with the Western traditions that have shaped us.

___________________________________________

For a very long time, we earnestly believed that our Christian social orders actually represented the Kingdom of God on earth.

___________________________________________

We, as Christians in North America, cannot help the fact that we function as heirs of a long and complex history that we define as “Christendom.” We have had a distinctive place and privilege in our social and political orders for a very long time, from the fourth century until well into the twentieth century. We became used to the idea that, as Christians and as the church, we were entitled to determine the shape of our societies. The church crowned kings as Christian monarchs, justified wars as holy, developed systems of social welfare as expressions of Christian charity, and received the state’s support to protect its institutions, its practices, and its convictions (up to and including the legal execution of heretics). Our holy days shaped the calendar, and we measured time in terms of the Lordship of Christ, anno Domini. For a very long time, we earnestly believed that our Christian social orders within this system of Christendom actually represented the Kingdom of God on earth.

There can be no questioning of the enormous benefits to Western civilization that resulted from the centuries of Christendom. Even a diluted and reductionist version of the Judeo-Christian legacy has had beneficial effects upon our societies at every level. The case can be made that this pervasive Christian witness through the centuries has permanently shaped the conscience of Western societies. The ancient biblical persuasion that every human life has an “alien dignity,” based on the fact that God created it and Christ died for it, continues to influence how we function. Still powerful in our societies are convictions that are basically Gospel-shaped: power should be limited and shared, the weak should be protected, wealth should be shared, family relationships should be honored, and individual potential should be encouraged and fostered. That the theme “social justice” is such a major pre-occupation of Western societies is attributable, at least in part, to the Christendom legacy.

A Matter of Control

Another side of that legacy, however, is the idea that we as heirs of Christendom are still capable of designing and building the kingdom of God, as we assumed we were doing during the centuries of an overtly Christian social structure.

It is fascinating to observe the language in the church today. We constantly read about the Kingdom of God and our role in it. But we find verbs being used that betray more of our Christendom self-confidence than a biblical sense of God’s rule. We are enjoined “to build” the kingdom, to “contribute to” the kingdom, to “extend” the kingdom, to “strategize” for the kingdom. It is a question of who is the subject of that action? Who is doing the exhibiting? In the New Testament, the reign of God is clearly God’s work: it is given to us, we are invited into it, we enter it as children, we receive it, and we are surprised by it. But we don’t have it under our control.

___________________________________________

While our narrow evangelism must reclaim the bold reality of the promised reign of God already taking shape in our midst, our overly optimistic approach to doing justice must be reshaped by the evangelical process of repentance, rejection of conformity, and transformation by the renewal of our minds.

___________________________________________

If the priority of evangelism is still marked by a reductionist drive for control, the case can be made that our commitment to social justice has a similar problem. We are a society shaped by the conviction that we can manage progress toward desired ends. We can explore and use the cause and effect nexus to manage outcomes. We can identify problems and solve them by dint of our human rationality and technological achievements. Where we see social problems to be solved, we can design the educational systems to produce people of virtue who will then solve the problems. We can even figure out what God’s rule is supposed to look like, draw up the blueprints and start implementing it.

When we, as Westerners and as Western Christians, engage the non-Western world, especially in areas of social need and crisis, we often betray our lingering sense of cultural superiority as we generously and self-confidently share the solutions we already have for anyone else’s problems. We still assume that our way of defining justice should be normative for everyone. We are still persuaded that God has given us the toolbox and the plans, and we should finish the work of building the Kingdom.

The Challenge of the Cross

The separation of these two priorities, evangelism and social justice, may also mean that we do our social strategizing while ignoring the Gospel’s uncovering of our sinfulness. The cross itself challenges the self-confidence of our inherited Christendom attitudes. Human designs for a just society are as fallible and sinful as the humans who design them. While our narrow evangelism must reclaim the bold reality of the promised reign of God already taking shape in our midst, our overly optimistic approach to doing justice must be reshaped by the evangelical process of repentance, rejection of conformity, and transformation by the renewal of our minds. Particularly as heirs of the Western Christendom tradition, we must be sensitive to our own reductionism precisely in our definitions of justice.

After the twentieth century disasters centered in the West, the Christendom legacy has become and will remain a problematic basis for any claims we might make to moral and ethical superiority. After two World Wars, the Holocaust, the environmental crisis, and the emergence of globalization as imposed by post-Christendom cultures on the rest of the world, we Westerners have a credibility problem when we postulate our ability to define what social justice is and ought to be. The Evangel’s way of empowering honest contrition and openness to regeneration must precede our attempts to “let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an everflowing stream” (Amos 5:24).

Merging Evangelism and Social Justice

How, then, can we overcome this false dichotomy? What would it take to merge the priorities of evangelism and social justice into one missional conviction that embodied them both and much more? This is the challenge that confronts us as a church tradition that inherits the legacy of Christendom but finds itself now in a strange new land—a post-Christian, post-Christendom mission field. The division into two priorities documents how little we have understood the dramatic changes in our context and what they mean for our vocation as a missionary church.

To overcome the dichotomy, we will need to follow the argument of Romans 12:2:

- recognize our conformities, our captivities to the mindsets and assumptions of Christendom still at work in us;

- experience the transformation by the renewing of our minds that will happen as we encounter in Scripture the fullness of the Gospel, which is Jesus Christ, who is the message, the messenger, and the embodiment of the reign of God;

- discover anew what is the good and perfect and acceptable will of God, without assuming that we already know the answers because of our Christendom legacy.

The problem of the false dichotomy between evangelism and social justice is also an opportunity for our continuing conversion, a conversion from reductionist understandings of both evangelism and justice toward a fuller vision of the Gospel. It will center on the person and work of Jesus, the concrete formation of his people for his service, and the realities of healing and hope that are the evidence now of God’s reign breaking in. It will work out of our common desire to learn together how to lead our life as a community, worthy of the calling to which we have been called—and to receive the Spirit’s power to do it.

[wpcol_1half id=”” class=”” style=””]

[/wpcol_1half] [wpcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Darrell L. Guder is the Henry Winters Luce Professor of Missional and Ecumenical Theology at Princeton Theological Seminary. He holds the Ph.D. from the University of Hamburg. Among his publications are Be My Witnesses: The Church’s Mission, Message and Messengers, The Continuing Conversion of the Church, The Incarnation and the Church’s Witness, and the edited study, Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America. More recently, he has translated Karl Barth’s Theology of the Reformed Confessions and Eberhard Busch’s The Barmen Theses Then and Now and The Great Passion.[/wpcol_1half_end]

[/wpcol_1half] [wpcol_1half_end id=”” class=”” style=””]

Darrell L. Guder is the Henry Winters Luce Professor of Missional and Ecumenical Theology at Princeton Theological Seminary. He holds the Ph.D. from the University of Hamburg. Among his publications are Be My Witnesses: The Church’s Mission, Message and Messengers, The Continuing Conversion of the Church, The Incarnation and the Church’s Witness, and the edited study, Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America. More recently, he has translated Karl Barth’s Theology of the Reformed Confessions and Eberhard Busch’s The Barmen Theses Then and Now and The Great Passion.[/wpcol_1half_end]

Banner photo by Dipu Das.

Unbound Social