Comité de Alegria: The Committee of Joy

If you remember, one of the marks of wholeness (shalom) was joy. To follow God we are to be a joyful people. This is really important for those who seek after justice, where change comes slowly and victories are few and far between. The importance of joy as a key attitude for working for justice is highlighted in a story told by Joyce Hollyday:

On the days leading up to Christmas a Honduran refugee camp was filled with Salvadorians who had fled the violence in their own country. Members of the National Guard were killing members of the community, and others were dying of starvation and disease… Despite the sorrow, when Christmas Eve came, the camp burst into joyful preparation. Women baked cinnamon bread in an adobe oven, while men butchered hogs for… special pork tamales. The children made figurines out of clay from the riverbed for the nativity scene… They painted beans and kernels of corn in bright colors and strung them into garlands. They made ornaments from small medicine boxes and shaped figures from the tin foil that wraps margarine sticks and hung these on a tree branch.

The children dressed as shepherds and passed from tent to tent, recounting the journey on Maria and José in search of shelter. “This Christmas we will celebrate as they did,” said one mother, “looking for a place where our children can be born.”

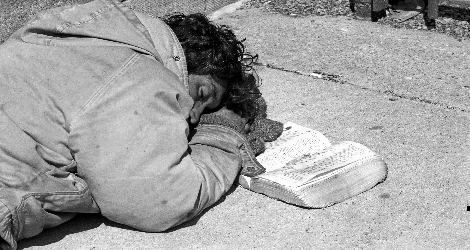

A refugee woman asked Yvonne Dilling, a U.S. church worker from Indiana in the camp, why she always looked so sad and burdened. Yvonne talked about the grief she felt over all the suffering she was witnessing and her commitment to give all of herself to the refugees’ struggle.

The woman gently confronted her: “Only people who expect to be back to the United States in a year work the way you do. You cannot be serious about our struggle unless you play and celebrate and do those things that make it possible to give a lifetime to it.”

She reminded Yvonne that every time the refugees were displaced and had to build a new camp, they immediately formed three committees: a construction committee, an education committee, and a comité de alegria—‘the committee of joy’. Celebration was as basic to the life of the refugees as digging latrines and teaching their children to read.(6)

This does not mean our work is not serious. Martin Luther King reminds us from his cell in the Birmingham city jail:

(W)e have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. History is the long and tragic story of the fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily… We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed… We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of (people) willing to be co-workers with God, and without this hard work, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation.

But working for justice over the long haul requires hope, a quality of joy.

Jim Wallis defines hope as “believing in spite of the evidence and watching the evidence change.” He tells a powerful story that took place when, to all outward appearances, apartheid still had a strangle-hold on power in South Africa and Nelson Mandela was still in jail. During an uprising, a public rally that had been planned by the religious community was canceled by the government, so a church service was held instead. Government police encircled the sanctuary as the service proceeded. At one point, Bishop Desmond Tutu stepped in front of the pulpit and pointed at the police presence, saying “You are very powerful, but I serve a God who will not be mocked, and I am telling you that apartheid is wrong and it is dead.” And then he said to the police, “Since you have already lost, I invite you to join the winning side; come into the midst of us and join in the dance.” The church’s congregation stood and began to dance and celebrate. At Nelson Mandela’s presidential inauguration, Jim Wallis asked Bishop Tutu if he remembered that earlier day, and Tutu said that indeed he did remember. Wallis’ reflection was that apartheid did not die on the day Mandela was released or inaugurated, but that it died the day of the celebration in the church. The government and culture of South Africa were changed by the hope in freedom as people of faith watched the evidence change. This is the hope that sustains us as we work for the Realm of God in our midst.

A Current Occupation Requiring Hope, Joy, and Justice

About a year ago, I visited a partner congregation in Palestine: the Evangelical Lutheran Christmas Church in Bethlehem, a place living under the evil of occupation. The minister there is Rev. Dr. Mitri Raheb who joined with over twenty other Christian leaders to write the Palestinian Kairos Document that was published in December of 2009.(7) They begin with a wonderful statement of hope and faith in the face of occupation:

We, a group of Christian Palestinians, after prayer, reflection and an exchange of opinion, cry out from within the suffering in our country, under the Israeli occupation, with a cry of hope in the absence of all hope, a cry full of prayer and faith in a God ever vigilant, in God’s divine providence for all the inhabitants of this land. Inspired by the mystery of God’s love for all, the mystery of God’s divine presence in the history of all peoples and, in a particular way, in the history of our country, we proclaim our word based on our Christian faith and our sense of Palestinian belonging—a word of faith, hope and love.

The problem is not just a political one. It is a policy in which human beings are destroyed, and this must be of concern to the Church.

We are back to the first benchmark of justice, that the image of God gives every person a dignity and a right to wholeness. The Kairos Document goes on to say,

We believe that every human being is created in God’s image and likeness and that everyone’s dignity is derived from the dignity of the Almighty One. We believe that this dignity is one and the same in each and all of us. This means for us, here and now, in this land in particular, that God created us not so that we might engage in strife and conflict but rather that we might come and know and love one another, and together build up the land in love and mutual respect.

“Hope,” they say, “is the capacity to see God in the midst of trouble, and to be co-workers with the Holy Spirit who is dwelling in us. From this vision derives the strength to be steadfast, remain firm and work to change the reality in which we find ourselves.”

Bishop Tutu, Dr. King, Dr. Raheb, and so many others have stood up for justice for all in the face of ferocious opposition. They stood in the tradition of the good King we hear about from Jeremiah,

Did not your father eat and drink and do justice and righteousness? Then it was well with him. He judged the cause of the poor and needy; then it was well. Is this not to know me? Says (God). (Jer.22:13-16)

All of us are called as well to know God by seeking justice and serving the poor.

Read Unbound’s article, “Bethlehem—More Besieged than Ever“.

____________________

Notes

- Joyce Hollyday, Then Shall Your Light Rise: Spiritual Formation and Social Witness, Upper Room Books, Nashville, 1997, p.14

- Christian Century, “Too much practice”, March 9, 2010, p. 22.

- “Too much practice”, p. 22.

- “Too much practice”, p. 23.

- “Too much practice”, p. 24.

- Hollyday, pp. 91,92.

- Kairos Palestine Document available at http://www.pcusa.org/media/uploads/oga/pdf/kairos-palestinestudy-guide-final-6-14-11.pdf

As Associate Pastor for Faith in Action at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Minneapolis, Doug Mitchell brings a history of leadership in urban mission agencies dealing directly with issues of discrimination, housing, youth, inclusivity, and other critical social justice concerns. Before coming to Westminster in 2001, Doug served as the President of the City Mission Society of Boston and as the Executive Director of Greater Birmingham Ministries. He holds a Master of Divinity degree from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and has done extensive additional graduate work in social ethics and urban politics. Doug has chaired the General Assembly’s Urban Ministry Support Team, 1989-1993, and served on the Urban Strategy Task Force, 1991-2000. He is on the Executive Committee of the Board of the Presbyterian Health, Education and Welfare Association, the PCUSA’s oldest and largest social justice organization.

As Associate Pastor for Faith in Action at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Minneapolis, Doug Mitchell brings a history of leadership in urban mission agencies dealing directly with issues of discrimination, housing, youth, inclusivity, and other critical social justice concerns. Before coming to Westminster in 2001, Doug served as the President of the City Mission Society of Boston and as the Executive Director of Greater Birmingham Ministries. He holds a Master of Divinity degree from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and has done extensive additional graduate work in social ethics and urban politics. Doug has chaired the General Assembly’s Urban Ministry Support Team, 1989-1993, and served on the Urban Strategy Task Force, 1991-2000. He is on the Executive Committee of the Board of the Presbyterian Health, Education and Welfare Association, the PCUSA’s oldest and largest social justice organization.

Banner graphic by Brit Brodeur.

Unbound Social